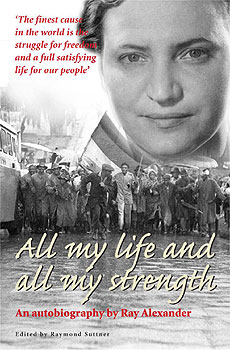

Ray Alexander Simons, founder member of Fawu, whose favourite slogan was “no corruption, no cover-ups”

5 September 2016

Three noteworthy and inter-related events were registered in South Africa during Women’s Month 2016: the 60th anniversary of the great anti-pass march on the Union Buildings, the 70th anniversary of the first major strike by the country’s black miners and the decision by the Food and Allied Workers’ Union (Fawu) to withdraw from the Cosatu federation.

What the three events, spanning more than half a century, have in common is one woman: Ray Alexander Simons. The founder member of Fawu, and one of the main Cape organisers for the 1956 women’s march, she was also an active supporter of the 1946 strike, despite being, at the time, seven months pregnant with her first child, Mary.

Known as “Mama Ray” to several generations of union activists, one of her favourite slogans, stridently voiced in the East European accent she never lost, was: “No corruption, no cover ups”. Which is why it seemed singularly appropriate that Fawu elected to leave the party politically enmeshed Cosatu federation during Women’s Month.

Given her history and her principled approach to trade unionism, Mama Ray would almost certainly have sided with the majority of members who decided last week to distance themselves from the corruption peppered political convulsions now sowing dissent within Cosatu and the governing, ANC-led, alliance.

And, were she around today — she died in 2004 — she would probably be just as vociferous as she was in 1997 when, aged 84 and the honorary life president of Fawu, she tore into the union hierarchy at its bi-annual conference. This at a time when the union leadership had become involved in an extremely messy business involving dividends, commissions, shareholdings and the purchase and sale of Krugerrands.

Such issues were not expected to be raised at the conference where the guest list included five Cabinet ministers, the deputy president and a clutch of ANC and Communist Party (SACP) luminaries. Rumblings of disquiet from the rank and file had been largely ignored and were not expected to emerge. But they had reached the ears of Mama Ray.

Shorty before the conference, word also reached the Fawu leadership that Mama Ray might be, at the very least, somewhat critical in her welcoming speech. So only “approved” media were permitted to attend the conference. It was the first — and only — union conference from which I have been physically ejected.

At the conference, Mama Ray discarded her prepared speech, and later repeated to me what she had said, the recording of it having been confiscated by the union leadership. Her version was also confirmed by gleeful delegates who had made notes.

Ray Alexander Simons’ message to the Fawu delegates was simple: “The union is yours”. While the ANC had inherited “a corrupt government”, Fawu members had not inherited a corrupt union. To a standing ovation, she roared: “No corruption, no cover-ups.”

It was a rather naive hope as the internal battles continued. But so too did the legacy of accountability and democracy laid down by Mama Ray and the early builders of the union. It is this that seems again to have come to the fore in the debates about leaving the ANC-led alliance.

Mama Ray firmly believed that the building blocks of a just and equitable future society lay within the ranks of the organised working class. As such, and despite her loyal membership of the Moscow-linked Communist Party, and the ANC, she remained a committed non-sectarian trade unionist.

A devout adherent to debate within the workers’ movement, she seemed never to allow her own convictions to interfere with the work of uniting workers And, along with privatisation of state assets, she vehemently opposed union investment companies and unions dabbling in the stockmarket.

“Trade unions should remember what their role is,” she chided. And she was a living example, having travelled through the farmlands of the Western Cape, sleeping on the floors of workers’ cottages as she recruited members to the union at “a tickey (three cents) a month”.

Her message from that time resonates now: “Never confuse the union’s money with your own.” These days of corporate union credit cards, of bodyguards and luxury hired cars would also have been anathema to her.

At the same time, like so many of her generation who had invested so much hope in the 1917 Russian Revolution, she could not countenance the idea that the revolution could have been strangled in its infancy; that poisoned by nationalism, and crippled by economic anemia, it could have become the mirror image of the very system it had so briefly overthrown.

But she never allowed this almost religious conviction to interfere with the work of uniting workers. And this meant supporting open debate in the workers’ movement, especially in the wake of the collapse of the Soviet bloc.

The Fawu decision indicates that the idea of principled unity across ethnic, gender, political and religious lines, of open and honest debate, appears again to be stirring; that the legacy of Mama Ray and her cohorts continues to survive.

Views expressed are not necessarily GroundUp’s