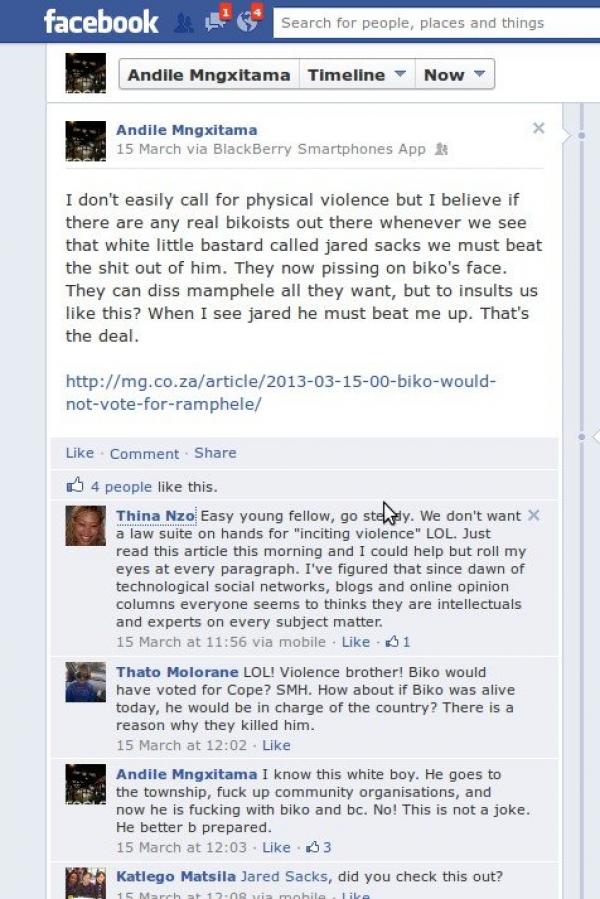

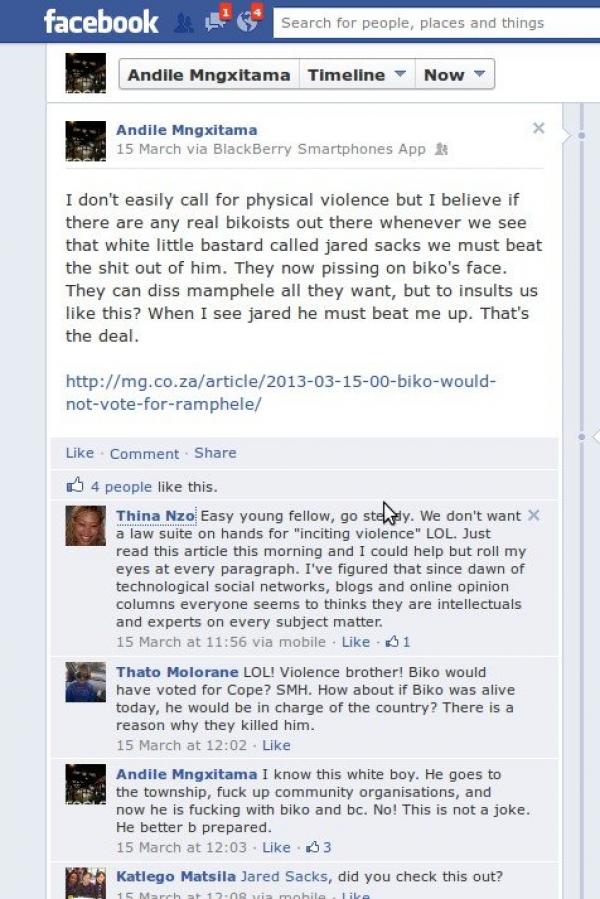

Screenshot of the Facebook correspondence in which Andile Mngxitama threatened Jared Sacks

27 March 2013

On the 15th of March Jared Sacks, a journalist and activist, published an article in the Mail & Guardian asking whether or not Steve Biko, the Steve Biko of 1977, would have supported Mamphele Ramphele’s recent political initiative. Some people, including people who had been close to Biko, really liked the piece. Others, including the well-known public commentator Andile Mngxitama, didn’t like it at all.

As a well-known public figure Mngxitama has easy access to the elite public sphere. He often writes in newspapers, appears on television and speaks at events of various kinds. But although he has so many platforms from which he can express his views he has become well known for hurling public insults at people, including younger black intellectuals and activists, with whom he disagrees. The insults that he has thrown around have included describing people as ‘CIA agents’, ‘askaris’, ‘house niggers’ and ‘white supremacists’. In many cases these insults have very little to do with reality and are just a form of polemical terror, a way of using labelling and intimidation to shut down debate and police the lines of what and who is presented as acceptable. This behaviour is, to say the least, very far removed from the intellectual flourishing that characterised the Black Consciousness movement in its heyday in the 1970s.

Mngxitama is certainly not the only figure in our public life that often prefers to try and intimidate people into silence with insult rather than to engage in real discussions. In fact this kind of intellectual thuggery, sometimes accompanied with violence, has often been at the centre of the left in and out of the ruling alliance. In some cases it has been romanticised in a way that confuses the intensity of an activist’s macho posturing with the seriousness of their political commitment. This masculinisation of the idea of political militancy has often pushed women and men who espouse more gentle forms of politics to the margins. But in his response to Sacks Mngxitama went beyond the usual polemical terror and actually issued a public call for violence against Sacks declaring that “[W]henever we see that little white bastard called Jared Sacks we must beat the shit out of him … “. Mngxitama is certainly not the only public figure to mobilise violent imagery for political purposes. Violent imagery and posturing have become increasingly common in the political culture of our elites since Jacob Zuma’s rape trial. It is always dangerous for public figures to use violent language against imprecisely defined ‘enemies’ – be they ‘criminals’, ‘neoliberals’ or ‘imperialists’. This kind of language aims to divide society into ‘us’ and ‘them’, good citizens and evil outsiders, in a way that demands obedience to leaders. It’s also very dangerous for the simple reason that activists who are breaking no laws can suddenly find themselves presented as ‘criminals’. In the crude propaganda of politicians like Sidumo Dlamini or Blade Nzimande people who are critical of Jacob Zuma can suddenly find themselves presented as ‘neoliberals’, ‘imperialists’ or ‘CIA agents’. Every dictatorship is ideologically grounded in this sort of abuse of language. And every major democratic upsurge across the world and throughout history has been rooted in a commitment to enabling ordinary people to think and speak for themselves.

But by publically calling for violence against a particular individual, a named individual, Mngxitama crossed a line that no other major figure in our public sphere has yet crossed. The silence of Jacob Zuma and his backers when there were calls for violence against Zuma’s accuser in his rape trial was scurrilous. But even then we did not see public figures go so far as to call for violence against named individuals. It is clear that the increasing violence, spying and intimidation by the State, ANC and SACP against dissenters on the Left or protesters is a dangerous development that must be resisted. But Mngxitama’s call for violence against a particular person in response to a newspaper article marks a new moment in the ongoing degeneration of our commitment to democratic norms. We have no doubt that if it is allowed to pass unchallenged it will be taken up by others, in and out of the ruling alliance, in a society in which democratic hopes are already battered by rapidly escalating political intolerance and violence.

As activists there is much on which we (Achmat and Pithouse) agree. For instance we have worked together on campaigns like the struggle against HIV denialism and pharmaceutical corporations. And we are looking forward to working together on attempts to build more effective solidarity for Palestine in South Africa. But there are also many issues on which we disagree. However one of the areas in which we are in firm agreement is that disagreement needs to be mediated through rational forms of engagement in which the possibility for mutual transformation is never foreclosed at the outset of a conversation. For this reason we are both committed to the struggle to defend and extend our public sphere, a space where disagreements can be discussed rationally.

We have both, in quite different ways, passed through forms of politics that imagined themselves to be emancipatory but which were, in reality, clearly authoritarian. In Achmat’s case this was a form of Trotskyism within the ANC in which the group imaged itself to be all knowing. In Pithouse’s case this took the form of a less formal network organised around a charismatic individual whose word was law and undergirded with a violent posture. We do not deny the tremendous value of the knowledge gained through past political affiliations. But in both of these forms of politics there was very little confidence in the political capacities of ordinary people and political commitment was measured by loyalty to the small group rather than success in changing the world. These kinds of political cultures invariably leave a lot of people damaged, especially people sincerely looking for paths into a more just future, while failing, completely - as completely as Mngxitama’s attempts to organise – to win real victories for real people.

Achmat is the director of Ndifuna Ukwazi. You can follow him on twitter @ZackieAchmat. Pithouse teaches politics at Rhodes University in Grahamstown.