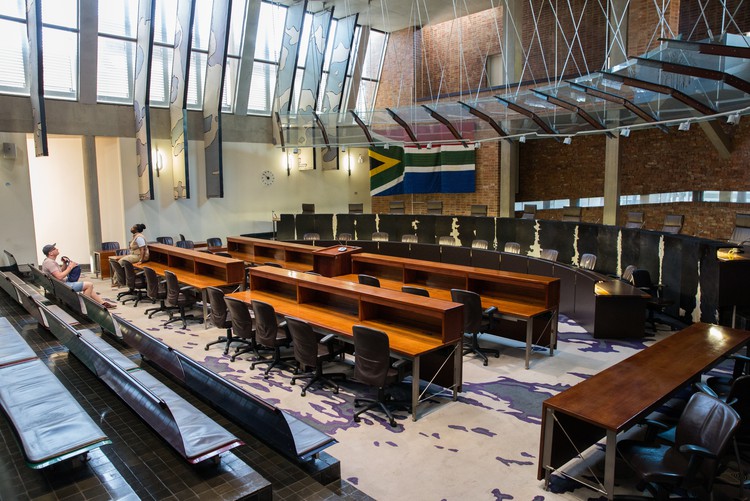

The Constitutional Court has ruled that asylum seekers whose refugee applications have been refused, can apply for a visa. Archive photo: Ashraf Hendricks

27 November 2018

If you are an asylum seeker and your application to be a refugee is refused, you are still allowed to apply for a visa. The Constitutional Court ruled this in a unanimous judgment handed down in October.

The case was brought by three asylum seekers whose applications for refugee status had been refused. They each then made applications for visas in terms of the Immigration Act.

Arifa Fahme applied for a visitor’s visa so that she could remain in South Africa with her husband and children. VFS Global, a company contracted by Home Affairs to process immigration applications, rejected her application because she was an asylum seeker. The company said that it cannot issue temporary residence visas to asylum seekers.

Kuzikesa Swinda and Jabbar Ahmed each applied for a critical skills visa. Their applications were rejected because their asylum applications were before the Refugee Appeal Board.

The main reason for all of the rejections however was a directive issued by Home Affairs in February 2016. This directive said that asylum seekers are only entitled to visas under the Immigration Act when they have been certified as refugees by the Standing Committee for Refugee Affairs. This effectively barred asylum seekers from applying for any type of visa.

Fahme, Swinda and Ahmed approached the High Court to set aside the directive. The High Court found that the Immigration Act and Refugees Act are complementary and not mutually exclusive. It found that the Immigration Act entitled foreign nationals to apply for a visa or permit.

The court reasoned that there was no reason to exclude asylum seekers from this definition. Also, the court found that denying Fahme the right to be with her family unjustifiably infringed her right to dignity. It ruled that Swinda and Ahmed should be entitled to critical skills visas if they otherwise met the requirements of the legislation.

Home Affairs appealed against the decision to the Supreme Court of Appeal (SCA). The SCA found in its favour. In a nutshell, the SCA found that it was impossible for the applicants to apply for permits in terms of the Immigration Act because such applications had to be made from outside the country.

The case then went to the Constitutional Court.

The Constitutional Court considered two main issues. First, whether an asylum seeker can apply for a permit or visa in terms of the Immigration Act. Second, whether the Directive should be set aside. PASSOP (People Against Suffering, Oppression and Poverty) joined the case as a friend of the Court.

Can an asylum seeker apply for a permit or visa in terms of the Immigration Act?

An asylum seeker is a person who has arrived in South Africa who asks to become a refugee. A person is eligible to be a refugee if they are fleeing another country due to persecution for their political beliefs or their membership of a particular social group. When a person enters South Africa as an asylum seeker they may be issued an asylum transit visa. This visa is valid for five days. During this period an asylum seeker must report to a Refugee Reception Office to apply for refugee status. If the application for refugee status is successful, the person is entitled to live and work in South Africa and may apply for permanent residence.

The Immigration Act allows any foreigner to stay in South Africa by applying for two categories of applications: temporary residence permits or permanent resident permits. The Act includes several different temporary residence visas such as spousal visas and critical skills visas.

An application for a temporary residence visa must be made at a South African embassy in the country in which that person lives.

The court found therefore that Ahmed and Swinda could not have applied for their permits in South Africa. Those applications had to be made from outside the country. The court found therefore that the SCA’s ruling in this regard was correct.

But the court then considered whether the directive should be set aside. It found that the directive imposed a blanket ban on asylum seekers from applying for a temporary residence permit or a permanent residence permit. The directive only enabled asylum seekers to apply for a permanent residence permit if they had been certified indefinitely as a refugee by the Standing Committee for Refugee Affairs.

The court then considered whether this particular interpretation of the Refugees Act and Immigration Act was justifiable.

It pointed out that unlike applications for temporary residence permits, applications for permanent residence permits do not have to be made from outside the country. Also, the court said, the Immigration Act entitled “any foreigner” to apply for a permanent residence permit and there was no reason to exclude asylum seekers from this definition.

The court noted that to request Fahme to leave the country and leave her family behind would be unfair and unjust.

For all these reasons the court found that to the extent that the directive imposed a blanket ban on an asylum seeker from applying for a permanent residence permit it was unlawful and must be set aside.

What about the applications of Swinda and Ahmed? The court said that unfortunately they were not in the same position as Fahme. Critical skills visas are a category of temporary residence permits visas and such applications can only be made from outside the country. However, the court pointed out that the Immigration Act entitles a person applying for a temporary residence permit to apply for an exemption from the requirements of the Act. This meant that Swinda and Ahmed were entitled to apply for an exemption in order to apply for their visas locally. The court pointed out that there was good reason to allow asylum seekers to apply for an exemption because they often do not have proper documentation and cannot return to their country of origin. The court found that to the extent that the directive imposes a blanket ban on asylum seekers from applying for a temporary residence permit it was unlawful and must be set aside.

Having worked in a state institution assisting refugees and asylum seekers for more than a year, I have witnessed first hand their plight. The asylum system in South Africa is critically understaffed and under-resourced. Many asylum seekers are struggling to regularise their stay and have no proper documentation. They need this in order to open bank accounts, find employment, run their businesses and improve their quality of life.

This judgment provides an alternative avenue for them to make a home in South Africa by applying for permits in terms of the Immigration Act. Hopefully the judgment will be a reminder that South Africa belongs to all who live in it, whatever their background or immigration status.