11 June 2020

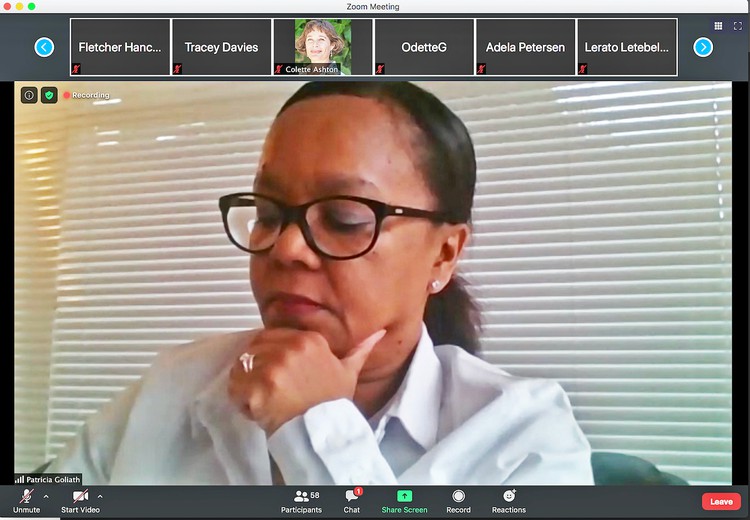

A screen grab of Western Cape Deputy Judge President Patricia Goliath during this week’s defamation case brought by Australian mining interests against six South Africans, which was held on a Zoom online platform with more than 60 participants.

In the R14.25 million defamation case brought by Australian mining interests against six South Africans – three attorneys and three community activists – Advocate Steven Budlender, appearing for the defendants, has drawn parallels with the infamous “McLibel” SLAPP suit in the UK.

That case, brought by giant global corporation McDonald’s against two British environmentalists, took more than 300 court days and nearly a decade before the Greenpeace activists were finally vindicated in the European Court of Human Rights.

SLAPP is an acronym for Strategic Litigation Against Public Participation, and was coined by American academics in the 1980s.

On Tuesday Budlender told the Western Cape court that although “McLibel” had not been called a SLAPP suit as such, it had demonstrated SLAPP principles and was similar in nature to the local case being made by the plaintiffs – namely, that it was legally legitimate to bring a defamation action that was intended to silence, censor and intimidate critics like the defendants, even if no damages were expected.

But “quite the opposite is true”, he argued – such action was not legitimate, and the attempt to silence his clients was “palpably” a breach of their right to freedom of expression.

On Wednesday, the second day of the two-day Western Cape High Court hearing, held on Zoom, Peter Hodes SC, for the plaintiffs, said there was a significant difference between the two cases. There had been no “equality of arms” in the McLibel case – a legal term referring to the need for a fair balance between the opportunities afforded the parties involved in litigation, such as bringing witnesses and cross-examination. The defendants in the South African case had three “very fine” counsel who were all acting pro bono.

Also, the local case was “very limited” and there was little disagreement over what the defendants had said that led to the defamation action – “We have it in black-and-white. The breadth of evidence is nothing like the McLibel case,” said Hodes.

He also argued that his clients’ case was supported by the fact that the British courts had allowed a corporation (McDonalds) to sue for damages in a defamation case – an issue under dispute in the local case. “McLibel, if anything, is very much in our favour,” he suggested.

The plaintiffs in the local case are seeking a total of R14.25 million in damages for defamation, or alternatively the publication of apologies. The defendants deny the defamation, or alternatively argue that the defamation was justified.

However, this week’s hearing before Western Cape Deputy Judge President Patricia Goliath was not about the merits of the defamation claims, which will be decided at a full trial to be held at a later date.

Rather, it was to consider the plaintiffs’ objections – legally, “exceptions” – to two special pleas that were also raised by the defendants.

The first special plea, titled “Abuse of process and strategic litigation against public participation”, relates to their argument that the defamation case against them is a SLAPP suit. They argue that the plaintiff’s conduct constitutes an abuse of legal process, and/or the use of court process to achieve an improper end and to use litigation to cause the defendants financial and/or other prejudice in order to silence them. They argue it violates their right to freedom of expression entrenched in section 16 of the Constitution.

The plaintiffs’ argument is that for legal proceedings like their defamation action to constitute “an abuse of process”, proceedings must have been brought without reasonable grounds and without clear merits – both of which they deny is the case here.

On Tuesday Budlender had challenged Hodes’s legal team to state outright whether they regarded it as legally permissible for a plaintiff to institute defamation action with the deliberate aim of silencing critics, without expectation of any damages.

Yesterday, Hodes’s colleague Johan de Waal SC, also for the plaintiffs, said in response they believed it was permissible to litigate in order to deter defamation, and he cited case history that he argued confirmed this point of view.

De Waal also described as “astonishing” and “a dangerous development” the defendants’ contention that SLAPP suits should be adjudicated by first examining improper motivation, before the merits of the actual alleged defamation were tested – “From our perspective, that’s a frightening development,” De Waal said.

He cited as an example a statement during a radio interview by one of the defendants, community activist Mzamo Dlamini, who had confirmed on air that he was accusing one of the Australian mining companies and its chairperson, Mark Caruso, of funding assassins to kill opponents of their Wild Coast mining proposals. These remarks form part of the defamation case.

“These are the kind of allegations we are dealing with here,” De Waal said.

He explained that if the defendants’ contention was successful, this would mean that someone could make a defamatory allegation such as “you are paying assassins” and then, if sued, defend it on the grounds of improper motive. The defendant could apply for a separation of trials and have the first trial testing only the improper motive claim, with the plaintiff being subjected to cross-examination, before the actual alleged defamatory remarks were tested.

“This is a completely unacceptable situation, we cannot allow our law to develop in this way,” De Waal argued.

The second special plea by the defendants, “Failure to plead patrimonial loss and failure to plead falsity”, was by agreement not argued at this hearing and will instead be taken to the Constitutional Court for adjudication.

Judgment has been reserved.

The plaintiffs in the case are Perth-based Australian mining company Mineral Commodities Ltd (commonly referred to as MRC); its chairman, mining entrepreneur Mark Caruso; MRC’s South African subsidiary company Mineral Sands Resources (MSR); and one of the companies’ BEE partners, Zamile Qunya.

MRC has been attempting to develop a titanium mine at Xolobeni in Pondoland for more than a decade, and has also been operating a mineral sands mine, Tormin, on West Coast beaches near Lutzville since 2014 through the subsidiary MSR.

Between them, the plaintiffs are bringing three defamation cases involving total damages claims of R14.25 million (or if those claims fail, for public apologies) against six local defendants: Wild Coast community activist Mzamo Dlamini, environmental lawyer Cormac Cullinan, former Centre for Environmental Rights’ attorneys Christine Reddell and Tracey Davies, Lutzville (West Coast) community activist Davine Cloete, and social worker, author and commentator John GI Clarke.

The cases are all based on critical, and allegedly defamatory, comments and statements made variously by these six defendants in media articles, radio interviews, public lectures, social media posts, books, a letter to the mining minister and/or emails to mining analysts and investors between 2014 and 2018, all relating to the operations of the two mining companies and the associated behaviour of Caruso and Qunya.