30 June 2025

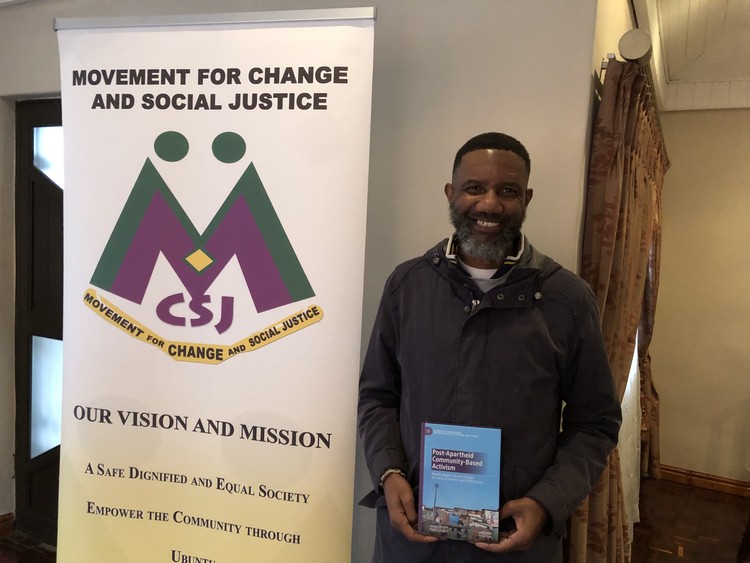

Two professors from the University of Massachusetts in the United States launched their book about the life of veteran activist Mandla Majola and the role he played in movements like the Treatment Action Campaign. Photo: Mary-Anne Gontsana

“I want people to remember my name, my contributions: serving, suffering and sacrificing for the community,” says veteran activist Mandla Majola. He was speaking at the Gugulethu launch of a book about his life and activism, dating back to the fight for access to HIV medication in the early 2000s with the Treatment Action Campaign (TAC).

The book, Post-Apartheid Community Based Activism: Mandla Majola and the Struggle for Social, Economic and Health Equity, is written by Professors Rajini Srikanth and Louise Penner of the University of Massachusetts in Boston, US.

Majola joked that he was hesitant when he was approached by the professors three years ago about their plan to write the book. “These professors used to visit the Treatment Action Campaign. They were impressed by my work and decided it was time to write a book about my journey as a social justice activist,” he said. “I don’t want the spotlight … but over time I realised the importance of the book.

The authors describe the book as “a timely, grounded study of community-based, human rights activism in contemporary South Africa”.

Majola said he got involved in the fight for HIV medication after his aunt, who had HIV, died in 1999. “I decided to learn more about HIV because what happened to my aunt really shocked me.” He joined the TAC, where he was responsible for campaigns on the prevention of mother-to-child transmission and on access to treatment.

He worked from the TAC’s Khayelitsha office and became involved in advocacy around gender-based violence and other community issues like water and sanitation.

“In 2010, Zackie Achmat asked me to help him at the Social Justice Coalition. We specifically looked at the xenophobic attacks in Khayelitsha. After these incidents were quelled, the SJC shifted its focus to water, sanitation, and the criminal justice system.”

He returned to the TAC in 2013 and worked there for three years until he graduated with a master’s degree in philosophy from Stellenbosch University in 2016.

He then got a job at the University of Cape Town’s School of Public Health, where he worked for five years. While working there, he and others formed the Movement for Change and Social Justice (MCSJ), which focuses on the public health system and gender-based violence.

Majola is currently completing a master’s degree in public health at UCT.

Neliswa Nkwali, from the TAC, said Majola was “the one who saw and pushed my passion for activism”.

“I survived cancer because of this man and the circle that we were all in,” she said.

“This book highlights the fact that we need to bring back real activism, back to the spirit that we had in the 2000s,” said Mike Hamnca, also from the TAC.

Tantaswa Ndlelana from the MCSJ said she felt “honoured” to be working with Majola. “I remember when we couldn’t get antiretrovirals. You led the path, and we fought until there was change.”

“Let this book be an inspiration.”

Majola was one of the TAC’s leaders for many years. The TAC was known for its uncompromising advocacy of scientific medicine. Yet Majola’s father was a traditional healer, an irony that the authors deal with. In fact, many leading members of the TAC found a way to balance this tension. An interesting part of the book is its description of the conflict between Majola’s father and his community, and how it came close to breaking the Majola family.

Majola’s father would treat anyone who came to his door, including gangsters. The community held this against him, especially because the gangsters usually won when they had conflict with the community. The book quotes Majola:

“There was a very difficult incident that happened in 1985. There was a family that had gangsters in my street. They were notorious in my neighbourhood, so the community decided … that they had enough these people [and my father for treating them] … And then one Sunday [community members] attacked [the gangsters]. And there was a huge fight. … My father had to flee. Then that … evening people came to our house, knocking around about 9-10 in the evening, singing, calling his name, [saying] that they’re going to kill him.”

The authors then explain that Majola’s father left to live on the family’s homestead in KwaZulu-Natal to stabilise his wife and children’s lives. But this forced separation was difficult for the family, which was “plunged into financial and emotional security”.

“In his absence,” Mandla tells us, “was the first time that I felt poverty.”

The authors quote Majola:

“We used to go to neighbours to ask for sugar … And my mother was working a night shift as a cleaner. After the community attacked our house, community leaders summoned my mother to the school that is closer to my home. My mother and older sister had to go there to account for my father’s activities and whereabouts. My mother was interrogated and insulted. They kept on saying, “but people are coming to see [my father] to consult.”

“I still remember that time vividly because I was frightened. People used to come at night every time that they had community meetings and I would be worried that they would come to our house and burn it down.”

When Majola’s father returned he was a broken man. The authors quote Majola:

“My father used to shave. He was not shaven: his beard was white. … [He had mismanaged] the money that he got from the municipality of Cape Town [after] he resigned because he used to drink.”

It is in telling these anecdotes that the book, which is mostly written in an academic style that can sometimes be difficult to understand for non-academics, is strongest and most readable.

The people who will most want to read Majola’s story are likely the residents of Gugulethu where he is well-known. So it is a pity that the book can only be purchased online for over R700 at the moment, a price that makes it inaccessible even for middle-class people, let alone working class people on the Cape Flats. Hopefully, the publishers, Springer, will make it more accessible in Gugulethu, perhaps by donating many free copies to the library and schools there.

Indeed Majola said he hopes to get help printing more copies of the book, to make it accessible to more people in townships.

The book is available for purchase from Amazon for $50 and online from Springer for €34.