Theewaterskloof Dam on 7 June 2016. It is 29% full. At the same time in 2012 it was 52% full. It has the capacity of almost all the other 13 dams supplying Cape Town’s water combined. It is the seventh largest dam in the country. Photo: Masixole Feni

8 June 2016

Six months have passed since the City of Cape Town tightened water restrictions on its customers, with no end in sight. In spite of the restrictions, water supply levels in the dams have fallen to extremely low levels.

As of 6 June, the combined supply of the dams is at 29% of capacity, the lowest level in the last five years at this time (see up-to-date weekly dam levels here). It is also the lowest of any week in records — albeit incomplete — that GroundUp has examined going back to July 2004.

In December, the City Council approved the implementation of level 2 water restrictions, to go into effect on 1 January 2016. These restrictions aim to reduce overall demand by 20%. Residential and business customers are required to reduce water consumption on gardens, cars, and paved surfaces.

All paying customers face increases in the price of water, but the City claims that customer bills should remain the same if they reduce consumption by 10%. Given the low levels of dams, the City has also warned that slight reductions in water pressure and quality may occur. Water allocations for indigent customers and the free monthly six kilolitre allocation remain unaffected. Stellenbosch and Drakenstein municipalities, which use an estimated 10% of the Cape Town’s water supplies, have also imposed water restrictions on their residents.

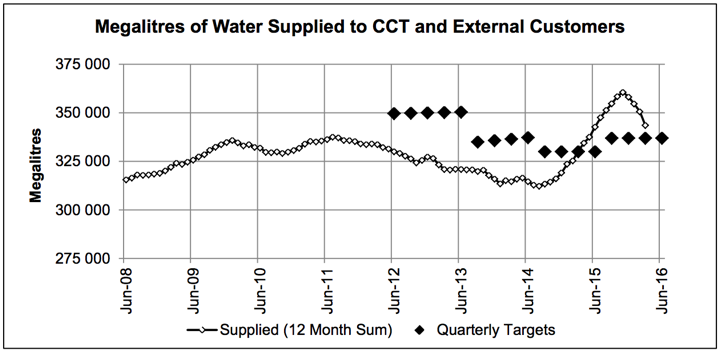

According to the City’s water utility report from 4 April, the level 2 water restrictions have succeeded in reducing water demand. Measured by a 12-month sum to account for seasonal variations, overall demand peaked in November 2015 at 360,000 megalitres. By March 2016, it had fallen to 343,000 megalitres (measured over the previous 12 months). The department believes it will soon achieve a target of 337,000 megalitres. However, if the drought continues, water supply will decrease while demand increases.

Cape Town’s water supply largely comes from rainfall throughout the Western Cape, particularly in the mountainous areas. Catchment areas funnel the rainwater to more than 14 dams throughout the province with a total capacity of 900,000 megalitres. From there, the water is chemically treated and distributed for customers to use. The national Department of Water Affairs and the City’s Water and Sanitation Department jointly manage this system. Cape Town uses 63% of the Western Cape’s total water supply.

The City needs the dams to be close to full capacity in October in order to last till the next winter. Last October, the dams were at 72% of total storage capacity. In the past five years, October water supply had never gone below 88%.

A megalitre is equal to a million litres. An Olympic swimming pool holds about 2.5 megalitres of water. The City of Cape Town supplies about 350,000 megalitres per year (enough water to fill 140,000 Olympic pools). There are about four million people in the city, so that works out to an average of approximately 250 litres per day per person. This also includes some water for agriculture and industry.

Even if the water restrictions and coming winter ease the current water supply problem, there are still concerns for future years. Dr Kevin Winter is a professor in environmental and geographical science at the University of Cape Town. He has conducted research on water sustainability. He sees the water shortfall as evidence that the climate is becoming increasingly unpredictable. As a consequence, he says the water supply will become uncertain and “social norms with regard to water demand will need to change.”

In the short term, Winter believes the City should be implementing more stringent level 3 restrictions, at least until it can definitely ensure adequate water supply. The Mayoral Committee Member for Utility Services, Ernest Sonnenberg, told GroundUp that level 3 restrictions would include tariff increases aimed at reducing water consumption by 30%. While the City has not published a detailed list of level 3 restrictions, similar restrictions by other municipalities included water outages during certain hours of the days, and substantial decreases in water pressure. Even though these restrictions could have short-term impacts on businesses and tourism, Winter believes the alternative of fewer restrictions would be much more damaging and chaotic.

In addition, factors such as increased urbanisation, population growth, and industrial development are predicted to strain the water supply. A 2009 newsletter published by the national Department of Water Affairs predicted that demand would exceed supply for the entire Western Cape region by 2019, and even earlier if Cape Town’s water reconciliation strategies were not effective.

The City’s Department of Water and Sanitation says that its water conservation efforts have been successful without too much inconvenience. It says that strict implementation of water restrictions and above target water reclamation efforts have contributed to decreasing demand in spite of the growing population. Sonnenberg said that any decision on water restrictions would depend on rainfall patterns in the next few months.

The City has also been taking steps towards ensuring future water sustainability. Currently, 6% of used water is reclaimed and used to irrigate sports fields, agriculture, and other industrial area with plans in place to increase that percentage. Since at least 2007, the City, in partnership with the national Department of Water Affairs, has been conducting studies into desalination plants, stormwater capture centres, and tapping unused aquifers. A R275 million project to divert winter runoff from the Berg River into the Voelvlei dam is scheduled for completion in 2021.

These projects aim to increase sustainability by drawing water from sources unaffected by rainfall. Still, the next few years will require consumers to take the initiative in personally saving water. For now, Cape Town anxiously awaits the winter rainstorms to fill its dams.

A correction was made to the explanation of the box titled Understanding water supply. We regret the error.