26 May 2020

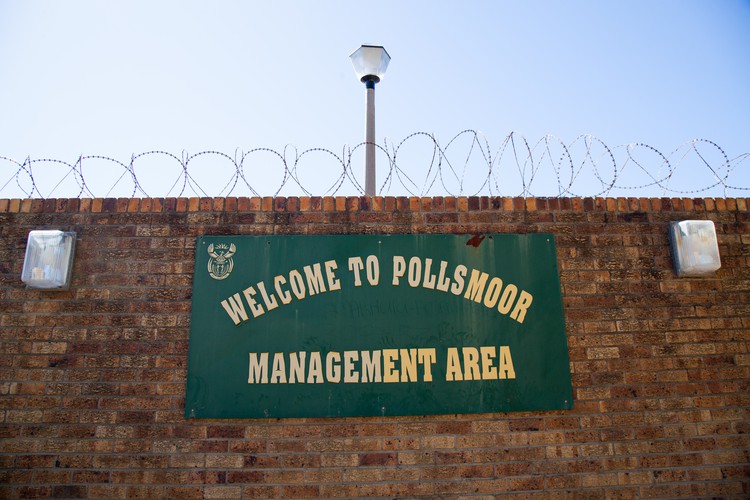

Earlier this month Minister of Justice and Correctional Services Ronald Lamola announced that 19,000 low-risk inmates would be released from South Africa’s overcrowded prisons. Archive photo: Ashraf Hendricks

Earlier this month Minister of Justice and Correctional Services Ronald Lamola made the long-overdue announcement that 19,000 low-risk inmates would be released from prison. It is a bold and necessary step to save lives as Covid-19 threatens to wreak havoc in South Africa’s overcrowded prisons.

Under the plan, people who have been sentenced for “crimes of need” would be eligible for early parole, with priority given to those with underlying health problems, the elderly (60 years and above), and women with infants.

Prisoners who meet the criteria for release will not be automatically granted parole; rather, parole boards will make decisions on a case by case basis.

Government has made it clear that people behind bars for murder, gender-based violence, child abuse, and other violent crimes will not be considered for release.

Social distancing is hard to achieve in our communities; inside our overcrowded prisons, it is impossible. Overcrowding obstructs attempts to curb the virus, exacerbates pre-existing health issues, and fuels the spread of other diseases such as TB and HIV.

Conditions are especially dire in remand facilities, which account for a staggering 30% of the prison population, and where remandees wait for months or years for the completion of their trials.

Government must move swiftly on its stated intention to assist people locked up only because of their inability to pay bail. These people should not be behind bars in the first place, and while one hopes they will not remain there much longer, the nature of the assistance government is considering has not yet been shared.

Compounding the problem are the more than 230,000 new arrests that have come with lockdown for violations of the Covid-19 regulations. While not all these cases are prosecuted, the majority are, and Covid-19 arrests have reportedly led to a 10% to 15% increase in remand detainees. Imposing custodial sentences, police records, and fines beyond many people’s means for lockdown violations conflicts with the restorative approach that government emphasised in its release decision.

Productive, restorative alternatives to placing people in custody and giving them criminal records — such as community service and a requirement to participate in educational programmes related to Covid-19 prevention — are desirable, and they are possible. It is equally concerning that government is detaining foreign nationals for immigration offences. There is no compelling public safety reason to continue pre-trial detention in such cases.

Even under the most ambitious release plan, many thousands of people will remain behind bars. South Africa’s prisons were dangerous before the pandemic; human rights abuses like rape and torture are widespread. During lockdown, these risks are multiplying. Oversight and monitoring of detention facilities are dramatically limited, and it is increasingly difficult for inmates to stay connected to family, friends, and loved ones. Those who were already vulnerable —including rape survivors, LGBTQ prisoners, and women — are likely to be especially hard hit in this crisis. It is essential, then, that we focus also on critical services for prisoners. Access to their legal representatives, psychosocial support, and oversight bodies such as JICS must be prioritised and facilitated.

Understandably, especially in a society so ravaged by violent crime, the release announcement has been met with fear, anger, and scepticism from certain sectors. But, the release of prisoners is about collective safety — the safety of all of us. Contrary to popular belief, detention facilities are not separate from the rest of us: whatever calamity unfolds there will affect us all. People are released from prison in the normal way of things; prison staff move daily between facilities and their communities, and so do many others (visitors and various service providers) in a non-lockdown context. If we’re truly concerned for the wellbeing of society, we will take whatever measures to stop the spread of Covid-19 in our prisons, and to uphold the rights of incarcerated people.

Covid-19 has amplified the emergency that South African prisons represent for society as a whole. For years, civil society organisations have criticised the over-use of incarceration — consistently shown not to work terribly well at rehabilitating people or reducing crime. The pandemic has led policymakers to rethink many aspects of our society. It is not naïve to hope that the same can happen with our prison system. We need to release — and stop locking up — people who do not pose a violent threat to our communities. And we cannot abandon the people who we know will not get out.

Views expressed are not necessarily those of GroundUp