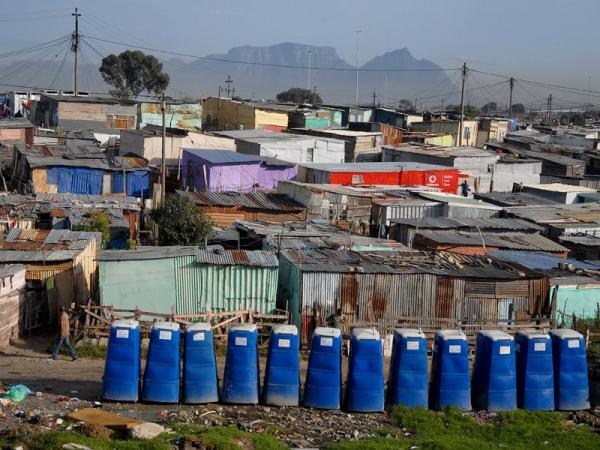

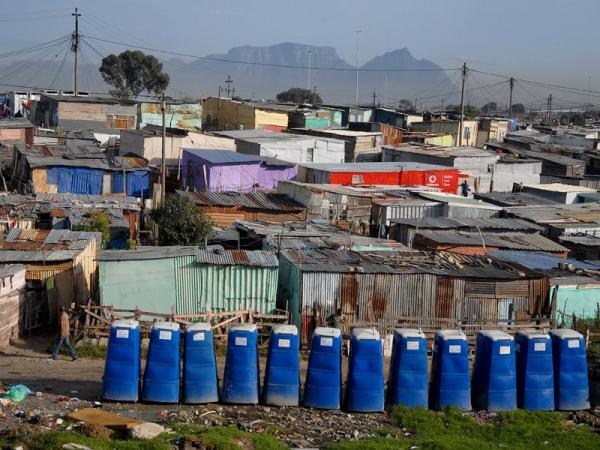

Row of portable toilets. Photo by Masixole Feni.

17 July 2014

Today, Mayor Patricia De Lille responded in a special edition of Cape Town This Week to the Human Rights Commission (HRC) report on sanitation provision in Khayelitsha that was published yesterday.

De Lille claims the HRC’s report contains misconceptions, and “displays an inexplicable lack of understanding of the legislative, financial and other factors which determine service provision.”

De Lille says 82 percent of Cape Town’s informal settlements face constraints that prevent certain types of sanitation provision. Such constraints include privately owned land, on which the City cannot legally provide sanitation services; high population density in informal settlements precluding full flush toilet infrastructure; and high water tables where full flush toilet installation is impossible.

“It is particularly astounding that the HRC can argue that the City’s provision of chemical toilets constitutes unfair discrimination,” De Lille says, noting that full flush toilets outnumber chemical toilets in Khayelitsha by fourfold. The City says chemical toilets are provided as a last resort and portable flush toilets are provided on a 1:1 basis per request.

De Lille also emphasises the City’s self-imposed guideline of a 1:5 toilet provision ratio, which, she says, no other municipality matches. She says sanitation provision is done “in full consultation with communities, especially as it relates to the location of such toilets.”

The Social Justice Coalition (SJC), however, believes De Lille still misses the point. “The mayor and the City don’t get the point of what the report is saying,” says the organisation’s spokesperson Axolile Notywala. “The City talks about the kinds of technologies, but they don’t have a plan for providing more sanitation for residents of informal settlements. They provide services on an ad hoc basis. The important point here is that a plan needs to be developed in order for every citizen to have sanitation.”

Notywala also says the City recognizes constraints but does not deal with them effectively. “We know some areas are in low-lying lands, but does that mean those people will never get sanitation?” he asks. “We’re not saying the City needs to install full flush toilets for everyone tomorrow, but they need a proper plan to look at each and every informal settlement and its conditions to overcome those challenges.”

The SJC is currently conducting a social audit of toilets in Khayelitsha, with data collected by residents as it was for the HRC report.

De Lille says, “While I respect the important role of Chapter 9 institutions, it needs to be understood that they are there to underpin our democracy, not to undermine elected governments and their electoral mandate.” She also writes, “I would also have expected this level of a lack of understanding of how government functions from the SJC, who deliberately misrepresent information to secure the funds necessary to underpin their annual R2.7 million salary bill.”

Notywala responds, “The SJC has nothing to hide. The City is free to have the SJC’s financial information, but they are running away from the real issues here, which are the rights violations of people in informal settlements. We conduct social audits not to get money, but to improve rights. It’s not about us. It’s not about the SJC or individual members of the SJC. It’s about the people living in informal settlements whose dignity and human rights have been violated by the City.”

De Lille says the City is determined to provide the best service possible to all residents, “unlike the ANC and the HRC who seemingly only have the race card left to play.”