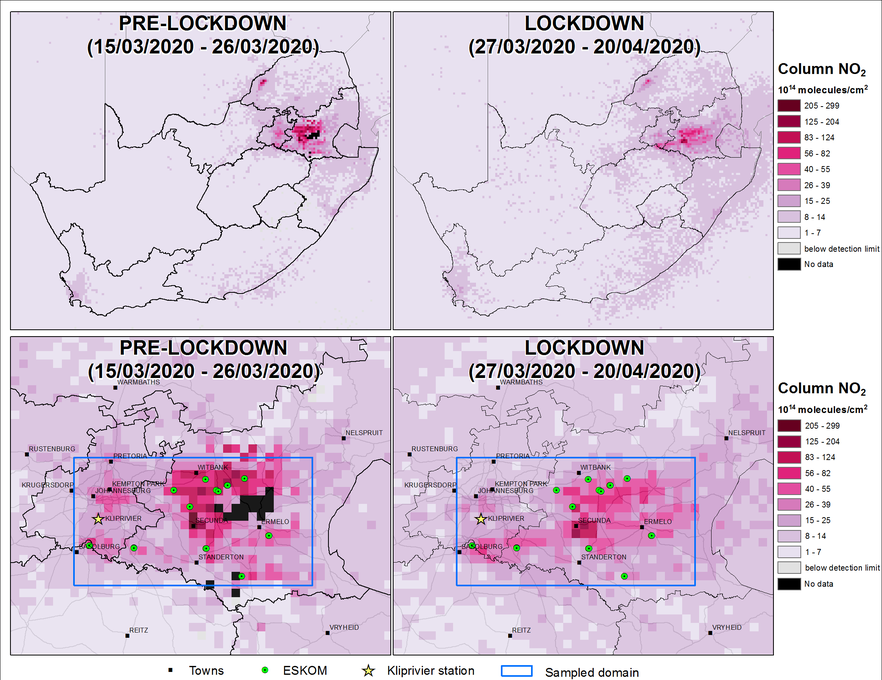

This graph shows the significant drop in nitrogen dioxide over parts of South Africa before and after the lockdown due to Covid-19. Source: CSIR/European Space Agency TROPOMI Sentinel-5P satellite

8 May 2020

A team of local and British scientists says air pollution levels have dropped by almost half in some parts of South Africa during the six-week Covid-19 lockdown, mainly because of lower emissions from Eskom power stations and heavy industry and an absence of bumper-to-bumper traffic.

The team, led by Council for Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR) principal researcher Prof Rebecca Garland, says preliminary analysis suggests that sulphur dioxide pollution levels have dropped by 47% on the Highveld since the lockdown began on 27 March, while nitrogen dioxide levels appear to have dropped by 23% over the same period.

This may be little comfort to people facing hunger or crippling job losses because of the lockdown, but air pollution is nevertheless a major global killer.

According to the World Health Organisation, air pollution causes about seven million premature deaths globally every year, largely as a result of higher mortality from stroke, heart disease, lung cancer and acute respiratory infections.

More than half of these deaths were due to ambient (outdoor) air pollution, mostly generated by power stations, factory fumes or traffic exhaust.

This graph shows the significant drop in sulfur dioxide over parts of South Africa before and after the lockdown due to Covid-19. Source: CSIR/European Space Agency TROPOMI Sentinel-5P satellite

Garland and her colleagues suggest that Eskom’s coal-fired power stations and heavy industry are South Africa’s largest sources of sulphur dioxide emissions, while the largest sources of nitrogen oxide pollution were from vehicle exhaust fumes, mining, fuel refineries and Eskom power stations.

South Africa’s latest air pollution results mirror some of the dramatic reductions reported from China, Europe, the USA and other heavily-industrialised areas since the Covid-19 lockdowns began.

Last month, Eskom also confirmed that electricity demand had dropped by as much as 9,000 MW a day during lockdown (roughly one third of the average pre-lockdown daily demand of 28,000 MW).

Garland stressed that the results are preliminary and also based largely on satellite observations from the European Space Agency’s Sentinel-5P satellite platform, which estimates pollution concentrations in the troposphere (from ground level to about six to ten kilometres above surface level).

She and her co-researchers (Seneca Naidoo, Mogesh Naidoo, Juanette John of the CSIR and Dr Eloise Marais from the University of Leicester in the UK) note that some pollution readings could be obscured on cloudy days. Because they were also based on daily snapshots recorded at about 1:30 pm daily over South Africa, they were not able to capture peak emission levels from traffic fumes during the early morning and evening rush hours.

Nevertheless, the data was valuable in the absence of detailed surface measurements from ground-based pollution monitoring stations.

The preliminary analysis is based on a comparison between pre-lockdown data (15 to 26 March) and the lockdown period (27 March to 20 April).

(Social distancing began on 16 March, with much less traffic from then, so the reduction in pollution might be bigger than measured, if compared to earlier dates.)

WHO graphic on air pollution

Garland and her colleagues note that air pollution has significant negative impacts on human health and that recent preliminary studies suggest there may be a higher death rate from Covid-19 in areas with severe air pollution levels.

Rico Euripidou, an epidemiologist and pollution researcher from the Pietermaritzburg-based groundWork environmental justice watchdog, said the national lockdown was an ideal opportunity for scientists to research local air pollution and health impacts.

“There have been massive drops in pollution levels in China and Northern Italy as the Covid-19 epidemic has unfolded over the past four months and we might expect to see some similarities here,” he said.

“The way that the air has cleaned up in some places with the Covid-19 lockdown is a remarkable testament to just how unsustainable the ‘normal’ economy - and ‘normal’ development - is. In many places around the world, young people are seeing a clear blue sky for the first time. And millions of people with asthma are breathing easier.”

Euripidou said there had been a major reduction in burning fossil fuels, which was the primary driver of air pollution globally and of the climate crisis. But this benefit was partial and short term.

“In South Africa, it is partial because many of our dirtiest plants, including Eskom’s big power stations, Sasol’s synfuels and chemical plants and Sapref, the country’s biggest oil refinery, are still pumping out pollution.”

“And everywhere it is short term because governments and big corporations want the ‘normal’ world back again … The poor and most vulnerable suffer most from the health impacts of air pollution and climate change, and they will suffer most from Covid-19 and the economic crisis. That will be used to justify a return to normal, but it is precisely the normal economy that made them poor and vulnerable in the first place.”

Euripidou pointed out that during the SARS outbreak in China in 2002 to 2003, a study by researchers at UCLA’s School of Public Health showed that patients with the disease were more than twice as likely to die from the disease if they came from areas of high pollution. (SARS, like Covid-19, is also caused by a coronavirus.)

“The same seems true of Covid-19: the more air pollution you are exposed to, the sicker you are likely to get. A Harvard study has just found the first correlation between air pollution and Covid-19 deaths in the USA.” (The study is not yet published in a peer-reviewed journal.)

WHO graphic on air pollution

Meanwhile, the International Energy Agency has described Covid-19 as the biggest shock to the global energy system in more than seven decades, with the drop in demand likely to cause a record annual decline in carbon emissions of almost 8%.

Dr Fatih Birol, the IEA Executive Director, said: “It is still too early to determine the longer-term impacts, but the energy industry that emerges from this crisis will be significantly different from the one that came before.”

“Resulting from premature deaths and economic trauma around the world, the historic decline in global emissions is absolutely nothing to cheer,” said Birol.

“If the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis is anything to go by, we are likely to soon see a sharp rebound in emissions as economic conditions improve.”