2 June 2023

While the number of murders has increased dramatically since Bheki Cele became Minister of Police in 2018, the homicide rate began worsening several years before he took over. Archive photo: Ashraf Hendricks

Any which way you slice it, South Africa’s homicide statistics are extremely grim. Over 27,000 people were murdered from April 2022 to March 2023, probably the highest recorded number in a single year to date.

Nearly the same number of people were murdered in 1994, at the height of the low-intensity civil war in Gauteng and Kwazulu-Natal, though the homicide rate now is still lower than that period because the population has grown from 40 to 60 million.

Murder (or homicide) is the most important and useful measure of crime. First, it is the most serious crime. Second, it is the most reliably measured crime: people often don’t report other crimes and bodies are hard to hide. Nevertheless, even the number of murders and murder rates over particular time periods are not consistently reported across sources. Here we have primarily relied on the South African Police Service data for murders per quarter and year, and we have used the Thembisa AIDS model (an extremely useful and reliable source for much South African data) for population estimates in order to calculate murder rates per year. All numbers are approximate. South Africa’s last published census was for 2011, which means that murder rates (which depend on population estimates) are increasingly difficult to estimate with confidence.

Until about a decade ago, the number of murders per year was declining. While still very high, we appeared to be getting violent crime slowly under control. Then this happened:

|

Year |

Murders |

Per 100k |

|

2012/13 |

16,213 |

31 |

|

2013/14 |

17,023 |

32 |

|

2014/15 |

17,805 |

33 |

|

2015/16 |

18,673 |

34 |

|

2016/17 |

19,016 |

34 |

|

2017/18 |

20,336 |

36 |

|

2018/19 |

21,022 |

37 |

|

2019/20 |

21,325 |

37 |

|

2020/21 |

19,972 |

34 |

|

2021/22 |

25,181 |

43 |

|

2022/23 |

27,272 |

46 |

Several facts:

Why has the murder rate got worse? David Bruce, a widely respected researcher on violence, policing and public security, points to several possible causes: declining police numbers, the proliferation of firearms and violent organised crime. He also suggests that the worsening economy could be contributing to increased violent crime. “This impact is most strongly concentrated in the four most populous provinces,” he told GroundUp.

The Western Cape is one of the most violent provinces and there have been more murders in the past year (April 2022 to March 2023) in the province than in any other year in the past decade.

|

Year |

Murders |

Per 100k |

|

2012/13 |

2,575 |

44 |

|

2013/14 |

2,904 |

48 |

|

2014/15 |

3,186 |

52 |

|

2015/16 |

3,224 |

52 |

|

2016/17 |

3,311 |

52 |

|

2017/18 |

3,729 |

57 |

|

2018/19 |

3,974 |

60 |

|

2019/20 |

3,975 |

59 |

|

2020/21 |

3,848 |

56 |

|

2021/22 |

4,109 |

60 |

|

2022/23 |

4,114 |

59 |

Over the past ten years, the province’s murder rate has climbed from just under 45 per 100,000 people to about 60 per 100,000 people.

Yet there appears to be some promising news in this. The number of murders in the fourth quarter (January to March 2023) is massively down compared to the same period last year, from 1,015 to 872. While it’s too early to say whether this is a fluke, there may be reasons to believe the effect is real.

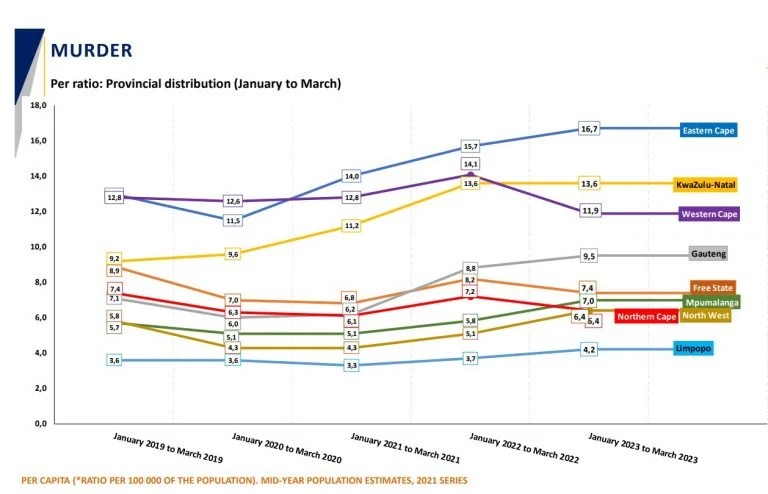

Murders rates by province for January to March (the fourth quarter of SAPS’s crime statistics period) 2019 to 2023. Note that the Western Cape and Northern Cape had strong declines. Murders in the Free State also declined, while murders in the rest of the country increased. Source: SAPS

Bruce says that a possible explanation for the Western Cape’s improvement is the different quality of engagement by the provincial government. “The available evidence is that the Western Cape government is directly involved with questions on how to improve safety in the province. There’s no clear evidence of anything similar in any other province and at a national level.”

“In the world of the analysis of crime trends, there’s an infinite range of explanations. But what is clear to me, is that the [Western Cape] government is engaging in the questions of safety in a way that is more advanced than the national government and also more advanced than other provincial governments,” he says.

Cape Town Mayco Member for Safety and Security JP Smith told GroundUp that the Western Cape has many safety challenges, including gangs, organised crime and drugs. “It is why the City has invested so heavily in its enforcement and emergency services for the past 15 years, and fighting for increased powers, to assist the SAPS to make communities safer.”

Smith said that in 2019, the City in partnership with the Western Cape Government, started accelerating law enforcement deployment in some of the worst crime-affected suburbs in Cape Town through the Law Enforcement Advancement Plan (LEAP).

LEAP officers are deployed in Delft, Gugulethu, Harare, Khayelitsha (Site B policing precinct), Kraaifontein, Mfuleni, Mitchells Plain, Nyanga, Philippi East, and Samora Machel.

Other high-crime areas in which they are deployed are Atlantis, Bishop Lavis and Hanover Park, along with Lavender Hill, Steenberg and Grassy Park, according to a recent statement by Western Cape Premier Alan Winde and provincial minister for oversight and community safety Reagan Allen.

“The statistics revealed by SAPS management show that we have made progress,” says Smith. “Many Cape Town policing precincts — once notorious for holding top positions for incidences of murder, attempted murder and other serious crimes — have dropped off these lists.”

Although there has been an improvement in the murder rates in the province, Smith acknowledges “that there is still much work to be done towards a safer Cape Town”. The Western Cape, after all, has the third highest homicide rate in the country.