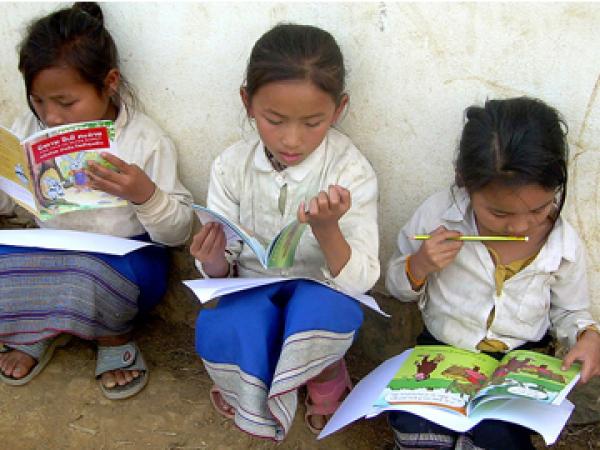

Three Lao girls sit outside their school, each absorbed in reading a book. Photo by Blue Plover (CC BY 3.0).

18 November 2013

Jack Lewis explains how we can quickly make radical improvements to primary school education.

As a primary school pupil I was rebellious and probably a bit lazy. Two things stand out as making a difference in my education. My father, seeing I wasn’t reading enough, insisting on reading Dickens’s Tale of Two Cities with me every evening before bed. He would ask me questions about what we had read. He was a disciplinarian, well educated and well read with wide ranging interests. And reading Wind in the Willows in school - each student with a book, our teacher, armed with a strap which he used on miscreants, calling out pupils names at random requiring each to read the next paragraph out loud. I learned how to pay attention, how to enjoy reading, how to think about what I was reading.

Crude and unacceptable as his methods were, even now – many decades later — I remember how focussed I was in reading class - yes “reading class”, a class where we learnt to read and concentrate and listen to others’ reading. Rebellious and loskop as I was, I forced myself to concentrate to be sure to know the place when my name was called. Once we reached the end, the teacher asked us our opinion of the story - I remember being the only student who said he did not like Wind in the Willows. I have since revised my opinion about Mr. Toad of Toad Hall - as with many other opinions.

I can’t shake the idea that if we could get all our young grade 1 to 6 pupils from poor “no-fee” schools reading and playing reading, writing and number games, we could break the backlog in primary education and set up a generation which would be able to – with some support – obtain meaningful matriculation results and proceed to tertiary or vocational training. The reading, writing and numeracy deficit set up in the primary school years remains and holds learning abilities back for life. This deficit is widely identified as the main reason for the poor performance of students in high school and their subsequent difficulties in employment and tertiary education. For the lofty National Development Plan to have any chance of success, we need a population that can read, write, comprehend and manipulate numbers fluently in English and in mother tongue.

The results of the 2012 National School Effectiveness Study, a massive six year exercise, are shocking and gives a clear idea of the scale of the problem. It showed that between Grade 3 and 5, few learners had reached the point where they could undertake sentence writing or exercise the “higher cognitive skills of inference and interpretation”.

These capacities underlie learning in all other subjects, including mathematics. The main reasons for the poor test results, says the study, are that “too little work is done in each lesson; teachers stick to low-level cognitive tasks and don’t involve learners in critical textual analysis”. And this is because the Study found that teachers own subject knowledge is “simply inadequate to provide learners with a principled understanding of the discipline”. The Study found that 70% of Grade 5 pupils at “no-fee” schools could not do a simple Grade 2 level addition correctly. The main reason for this poor performance is *the inability of the teachers to answer these simple questions correctly. *

The National School Effectiveness Study tries to be positive, providing a long list of fixes for the poor state of education. However, it recognises that nearly all of these fixes — such as time management or setting extending writing tasks, improved teaching of English — will have a limited impact unless something is done about basic reading, writing and numeracy and the quality of teaching radically improved.

The National Development Plan includes improvement in the quality of Education as critical for getting SA working by 2030 - a mere 17 years from now. It aims to “Improve the school system, including increasing the number of students achieving above 50 percent in literacy and mathematics, increasing learner retention rates to 90 percent and bolstering teacher training.” All these depend on the quality of teachers and someone being strong enough to take on SADTU to agree to performance monitoring, retrenching many principals and developing much better managed schools.

How do we break the vicious cycle of mis-education that is preventing South Africa from moving forward? We would do well to look at the experience of Nicaragua’s National Literacy Crusade that achieved a radical reform of the education system and reducing the overall illiteracy rate from 50.3% to 12.9% within only five months. While our goals would be different with a programme aimed primarily at children in Grades 1 to 7, some of the methods are relevant.

Using tertiary students, a new education system was established with very clear performance criteria and students and volunteer teachers were quickly trained to teach the system. In our situation in South Africa what is needed is intensive reading, writing and numeracy classes - irrespective of content knowledge. This would include puzzles with the names of the continents, shapes and sizes games, age appropriate well written books to be read in reading class sessions - basic education indeed. These additional classes could take place in school hours and in additional hours. There is a strong case to be made for a national service scheme in which all tertiary graduates not already drafted (doctors and nurses mainly) work for a year in such a programme.

In Nicaragua a series of record-keeping documents and tests were devised to determine the progress of literacy students during the campaign. The lack of regular testing, feedback, correction and support by teachers is one of the main things retarding learning. A new system with new methods has to be established in parallel to the existing schools both to make up for these appalling literacy and numeracy deficits and as a means of exerting pressure on the school system to change its work habits.