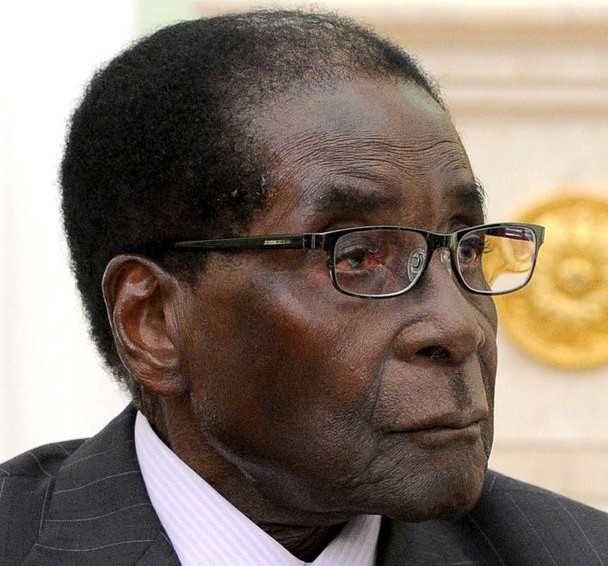

Robert Gabriel Mugabe: 21 February 1924 – 6 September 2019. Photo: Kremlin via Wikipedia (CC BY 4.0)

6 September 2019

On the day of Robert Mugabe’s death, and against the backdrop of xenophobic violence in South Africa, here are four personal stories by GroundUp’s Zimbabwean reporters that show what Robert Mugabe meant, not only to them, but many Zimbabweans.

The death of Robert Mugabe today brings a sigh of relief to millions of Zimbabweans whose lives were wrecked by his totalitarian rule. Personally I say his passing away (not on) was long overdue. Good riddance.

I grew up in Harare where my father was a furniture salesman travelling the width and length of the country sourcing orders. He made at least two trips a month to the Midlands and Matebeleland provinces where the army launched a scorched earth war against the Ndebele people in an operation called Gukurahundi (sweep away the dirty).

My father survived the army’s impunity because he was a Shona — the army did not kill Shonas — and he also survived the Ndebele vengeance because he could speak their language fluently. He told us gruesome accounts of Ndebele people who were shot execution-style because they could not speak the Shona language. The army killed men, women and even disabled people. It is estimated that about 20,000 Ndebeles were murdered.

I hate Mugabe because Gukurahundi sowed the seeds of hatred and tribalism between Shonas and Ndebeles, and the animosity is even getting worse.

Mugabe created and promoted corruption that eventually brought the economy of the country to its knees resulting in poverty, unemployment and the breaking down of families as millions of people emigrated to foreign countries seeking a better life.

People died of treatable diseases while he refused to release money to buy medicines.

Mugabe is the equivalent of Hitler as far as homophobia and racism are concerned. His devastating land expropriation of white-owned farms was nothing but a disaster. Instead of putting a pragmatic land reform process in place, he gave the land to his trusted people and senior army generals.

Operation Murambatsvina of June 2005 (he who refuses the rubbish) is one of Mugabe’s cruel legacies. He demolished without notice or a court order informal settlements that had mushroomed in Harare. People were thrown out of their houses and left stranded in the cold while the government offered no assistance to the victims.

Lastly, I personally witnessed three women being washed away by an over-flooded Limpopo River as they attempted to cross illegally into South Africa. The disaster happened in March, 2003 at a popular crossing point called Chivara, west of Beitbridge.

I blame Mugabe for making us suffer in foreign countries. I would confidently say if it was not for Mugabe’s impunity, xenophobia would not be known in South Africa. His unpopular policies of evicting white farmers, industrialists, non governmental organisations and the muzzling of the press resulted in disaster that triggered a mass exodus of Zimbabweans to other countries.

The list of his crimes is endless.

Born and educated in rural Zimbabwe, I thought our 1980 independence was going to bring everlasting freedom. Alas, little did I know that freedom was going to be short-lived.

Yes, Robert Mugabe the former Zimbabwean president who ruled the country for nearly four decades contributed to the well being of Zimbabweans but mostly to those who shared his politics.

From 1980 the Mugabe-led government opened a lot of schools and introduced free primary education. This was no doubt a great stride taken by his government.

In the early 1990s I noted the freedom we cherished was gradually fading.

From 1998 till 2007 I worked in one of the Zimbabwean government departments. I was already married and blessed with four children. My aim was to get my children educated but this was really tough for me. With the little salary I was paid I could not manage to send them to better schools, rent a house in town and support my parents.

Realizing that I could not meet all the basics my wife started informal trading. She had battles with municipal police because informal traders were not allowed to sell their wares in town. This was a blow to our family. My wife had to join other cross-border traders.

From 2006 she sold doilies in Cape Town until she realised that there was a chance for me to get informally employed in the construction industry in Cape Town.

I liked her idea. I was earning trillions of worthless dollars a month in my government job. Largely because of Mugabe’s land reform programme, the Zimbabwean currency had crashed and we could barely get by.

So to test out South Africa, I took a month’s leave and travelled to Cape Town. I joined fellow Zimbabweans at places where people wait to be hired for a day’s work.

But this was a very different situation from what I was used to in Zimbabwe. In Cape Town I usually got hired twice a week earning R120 per day. I was not used to this type of work but because I wanted my children to get the necessary education I had to force myself to do these odd jobs.

When my one month’s leave was over, I had a difficult choice: If I returned to Zimbabwe would I be able to pay my children’s school fees? On the other hand, the type of work I was doing in Cape Town was hard for me.

Should I leave my formal employment in Zimbabwe for odd jobs in South Africa? This was really a tough decision. I opted to resign. Ultimately the economic situation back home was too desperate. I decided to live in a foreign country doing work I had no stomach for.

Looking back at the excitement of Zimbabwe’s dawn in 1980, I wondered where it went wrong? Why did I end up living in a foreign country? Why should I be separated from my family for almost a year? Who is going to nurture the children when we their parents are in South Africa trying to raise their school fees?

I still don’t have answers to these questions. Gradually I have accepted that I have to fend for my family in a foreign land.

The death of Robert Mugabe has been met with little or no sympathy by Zimbabweans living in Gauteng. This has been worsened by the latest xenophobic attacks across the country. Many feel that there isn’t much of a home to go back to after the damage which was caused by Mugabe and his allies’ tyranny.

Bheki Sibanda is a Zimbabwean Ndebele who was displaced from his rural home in Nkayi in Matebeleland. He was only six years old at the time but says he remembers the pain he felt when Mugabe’s people forced him and his family to flee his home during Gukurahundi, in 1983.

“Our home was always under attack because they suspected that my uncle was a member of Zipra,” he says. Sibanda says all the wealth his family once possessed was left in shambles.

“We had everything: cows, goats and a nice home. But we had to leave it all behind because they promised to kill us.”

Sibanda says they had to board a bus during the night. They left their home for good and have never returned. Later all their wealth was taken, their home looted. To date Sibanda lives in Johannesburg and does not have a rural home to take his family to.

“Nothing was ever the same,” he says.

He makes a living today as a cross-border trader between Zimbabwe and South Africa.

“l am aggravated by xenophobic attacks in South Africa but l have to fight to build my family the home we lost. All of it happened because Mugabe was a tribalist and he caused great hatred between Ndebeles and Shonas.”

I am a 40-year-old economic refugee.

I had a true rural upbringing in Chikwaka, Mashonaland. I lived in Goromonzi district, about 80km from Harare. I started my education at a day school, St Francis Udebwe Primary, in 1984.

My father was a famous farmer. He supplied fresh produce for the whole district. He specialised in market gardening and chicken rearing. My mother was the one in charge of transporting produce to Harare for market. The proceeds paid for my education.

I enjoyed life until 2005. After the land grabs my life changed for the worse.

Robert Mugabe is the only Zimbabwean president I knew. It’s true he loved power and he overstayed his welcome but I adored him. I loved the way he used to speak with conviction. He was a public speaker. I envied his English. I am proud to be who I am today and believe it is because of some of the policies of Mugabe that contributed to my successes.

I believe he did well. I can safely say everyone in my village including the elderly can read and write. Mashonaland East has many top high schools. The best ones such as Goromonzi High, St Johns Chikwaka, St Ignatius and Bernard Mzeki are within my vicinity.

At St Francis school both primary and secondary where I did my Ordinary Level (O level), school was a place of learning only. Misbehaviour was never tolerated. At the age of seven, I made a decision about my life, what I wanted to be: a journalist. The environment enabled me. At that time teachers were also mature, loving and caring.

Relaxed hair was not allowed in school. All children, both females and males, maintained short hair. Even now most Zimbabwe schools have a short hair policy. The belief is that hair issues distract learners from learning.

There was also a policy of no speaking Shona during school times except in Shona lessons.

From Grade R in Zimbabwe learners were encouraged to speak English in school. Those who were caught speaking Shona were punished. As a result my confidence in speaking English grew at a young age. As a result when I started secondary school I did not struggle with English literature and essay writing.

The Ministry of Education monitored and invested in schools.

In the seven years I spent at Udebwe Primary school, the Minister of Education visited our school several times. It meant a lot to my friends and me especially because we were at a rural school. Our school had electricity, a science laboratory, library and internet.

My rural home is well developed. We have a hospital called Mabvudzi and a clinic opposite St Francis secondary. There are communal boreholes for people who cannot afford to dig wells in their homes. During my time in the village there were community development officers who monitored children’s nutrition and ensured that every household had a toilet.

However problems arose around 2000 when people from my village invaded surrounding farms. The commercial farmers were the pillar of our economy. Some of them were my father’s friends. They lent and borrowed farming equipment from each other and shared farming Ideas. What people from my village did was purely greedy because in Chikwaka we have vast rich agricultural lands which no-one is utilising.

The new farmers in my home area caused deforestation and destroyed farming equipment. Winter farming and green mealies the farmers used to plant in October ahead of the main planting season in December have vanished.

It is believed the land was shared among ZANU PF members and the masses who were supposed to benefit didn’t. President Mugabe failed to stop his people from grabbing the farms. $15 billion (US dollars, not Zim) diamond mining revenue was never accounted for. Poor management of the economy by the former president also drove me out of my beloved country.

At this point in my life I should be living in Zimbabwe contributing towards development and sharing my journalism experience with fresh students. But here in South Africa I am stuck, my future uncertain.

Zororai murugare baba vangu. [Rest in peace my father]