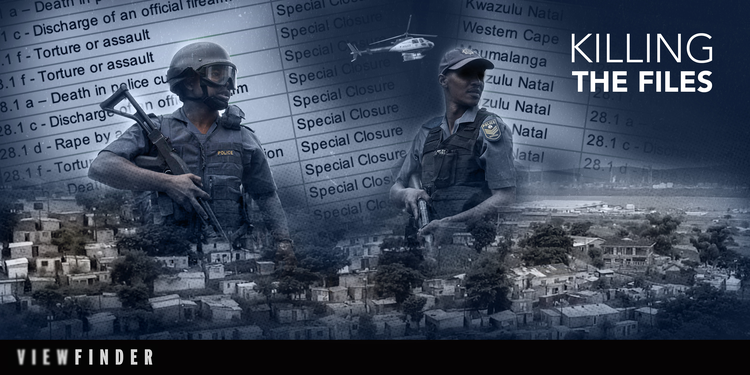

Viewfinder unpacks the mysterious “special closures” category, the high-water mark of at the Independent Police Investigative Directorate (IPID) cover-up. Poster design by Alex Noble, with archival photo by Ihsaan Haffejee for GroundUp

18 November 2019

Viewfinder unpacks the mysterious “special closures” at the Independent Police Investigative Directorate (IPID) during former director Robert McBride’s suspension. Last month, IPID management promised to release its report into these closures. Parliament set a date to receive it. Both institutions have since gone quiet. Meanwhile, new stories of victims likely denied justice continue to emerge from the data.

The Independent Police Investigative Directorate’s intake registers are replete with complaints of heinous crimes by police officers across South Africa. One originates from a small, rural township in northern KwaZulu-Natal on the evening of 29 June 2014.

It recounts how Zikhona Hadebe*, a woman in her late twenties, got into a fight with her partner. The fight was apparently severe enough for her to call 10111, the police emergency hotline, for help. The operator told her to sit tight; officers were on the way to assist.

A police van soon arrived. There were four officers inside. Hadebe got into the vehicle and the officers said that they would take her to the station. Instead, the driver drove them to the nearby town of Empangeni. One of the officers “injected” Hadebe with something. She was “told to sniff drugs”.

According to the complaint, Hadebe then “passed out and was repeatedly raped”.

Hadebe’s complaint was first registered as a rape case at her local police station. But, because the suspects were police officials, the docket was referred to IPID’s KwaZulu-Natal office.

Exactly 392 days later, case worker Smanga Nkwanyana closed Hadebe’s file as “Indeterminate” which, in official terms, meant that he was “unable to prove the allegation”.

In October, Viewfinder exposed that IPID investigators and their managers had taken short-cuts on investigations in a bid to inflate performance statistics. Whistleblower reports suggested that the practice was systemic, widespread across South Africa, and had evolved over many years.

Days after Viewfinder published, IPID acting executive director Victor Senna committed to publish the directorate’s own report on statistical manipulation. That report’s scope is expected to be quite narrow. It will only look at a limited number of cases that were apparently closed prematurely between mid-2015 and mid-2016. The scope, as Viewfinder understands, would however include an analysis of the Hadebe rape case file.

In IPID’s data, certain hallmarks in the closure of the Hadebe case suggest that the closure was, likely, an instance of statistical manipulation. For one thing, Nkwanyana (the IPID investigator) approved the closure of a case in which he was also the “case worker”. Doing so was prohibited by IPID’s quality assurance safeguards.

Yet, it is the “special closure” status, which Nkwanyana assigned to the Hadebe case, which presents the biggest red-flag. Since KwaZulu-Natal and Gauteng whistleblowers flagged it with head office in 2016, the term “special closure” has become associated with statistical rigging at the IPID.

When former IPID director Robert McBride testified at the Zondo Commission of Inquiry in April, he said: “The provision of special closure in the Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs) was abused to prematurely close cases or bring them to finality so that it can appear that IPID has gone through all these cases at rapid speed.”

McBride was reflecting upon happenings at the IPID during his 18-month suspension.

“Special closures” often meant that IPID officials used their discretionary powers – for instance that a case was “Unsubstantiated” or “Indeterminate” – in order to close and archive cases, instead of investigating them properly and referring the completed dockets for prosecution.

IPID data shows that 1,586 cases were dispensed of as “special closures” between June 2015 and September 2016. Like the Hadebe rape case, the overwhelming majority of these were from KwaZulu-Natal.

IPID’s 2015/16 Master registers show that hundreds of cases were disposed of as “special closures”. McBride reported at the Zondo Commission that this was done to manipulate statistics. Photo: Daneel Knoetze

Viewfinder’s investigation suggests that the use of “special closure” to “kill files” — as one whistleblower put it — was the high-water mark in a long history of statistical manipulation at the directorate. (Read the key take-aways from our first report for an overview of our findings.)

In April 2017, management at IPID KwaZulu-Natal assured the Auditor General that the “special closure” function on the case management system had been disabled. Poorly handled “special closure” cases were also apparently re-registered and re-assigned for investigation.

At the time, an IPID head office investigation into statistical manipulation, initiated by McBride on his return from suspension, was also reportedly underway.

Nearly three years later, and only after Viewfinder’s exposé, IPID management promised to publish its findings and present these to Parliament.

Parliament’s Portfolio Committee on Policing (PCP) chair Tina Joemat-Pettersson welcomed the news and set a date for the presentation. After numerous postponements, the presentation date has now been reset for 27 November. Committee spokesperson Malatswa Molepo said that this was to grant IPID an extension.

“The Committee takes the IPID investigation seriously and we eagerly await the results of the investigation in order to re-establish the public trust in IPID,” he said.

Meanwhile, Viewfinder has received a number of requests for help from victims or victims’ families. One of those coming forward, spoke of a mother’s agony. She had committed suicide four months after her 23-year-old son was found hanging in a police holding cell. “I want justice for my family, please help,” the message concluded.

There are thousands of descriptions of alleged crimes by police officers recorded in IPID’s intake registers. Apart from the descriptions of rape, one trend has stood out: the speculative torture of people by police officers on the hunt for guns, drugs, stolen wares or suspects.

This case description, which originates from Hazyview in Mpumalanga in 2015, illustrates the point: “The victim … was at her home when police arrived looking for her husband … She told the police that the husband is not available and the police proceeded searching the house but still couldn’t find anything. The victim was handcuffed and suffocated with a plastic bag that was wrapped on her head. The members also went to the wanted [person’s] mother who also suffered the same fate of being handcuffed and suffocated with a plastic [bag] wrapped on her head.”

Almost none of these cases progress through the investigative and prosecutorial pipeline to an outcome in court. One has to presume that the perpetrators get away and, in all likelihood, remain in uniform.

Many cases move suspiciously through IPID’s case management system and are prematurely completed or closed. An analysis of each investigation, a vetting of each docket, is now imperative.

Viewfinder understands that IPID’s awaited report to Parliament is rooted in docket analyses of the 1,586 “special closure” cases. If done properly, this may represent the tentative start of an important process of reflection and reckoning at the IPID. But, data anomalies and whistleblower reports dating back to at least the late 2000s suggest that much more may be needed for a full picture of the cover-up to emerge.

Viewfinder phoned IPID’s KwaZulu-Natal office to put queries to Smanga Nkwanyana (the investigator who closed the Hadebe rape case). An official there said that Nkwanyana had been an investigator at IPID KZN until his death in 2017. Further questions about the case, special closures, and the delay in IPID’s report to Parliament were sent to IPID acting executive director Victor Senna, IPID national head of investigations Matthews Sesoko and IPID spokesman Sontaga Seisa. These all went unanswered.

*Not her real name