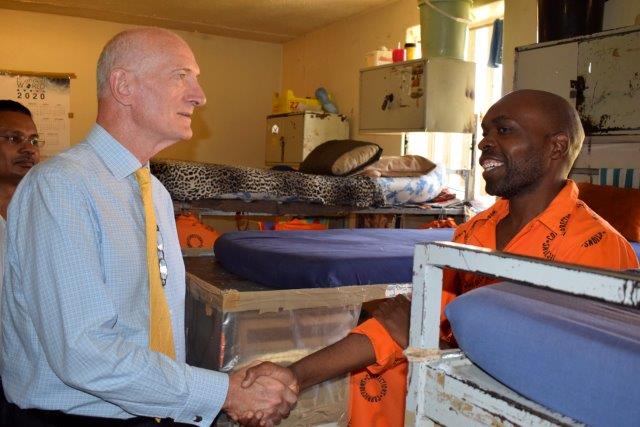

Judge Edwin Cameron talks with Mthunjelwa Johannes Manganyi at Zonderwater. Photo supplied (Manganyi gave permission for the photo to be used.)

3 March 2020

The end of apartheid brought about a remarkable change in the way we approached crime and punishment. The world’s most famous former “criminal”, Nelson Mandela, now President of South Africa’s constitutional democracy, had experienced the viciously punitive, small-minded, worst of apartheid’s prisons. His government abandoned the retributive approach apartheid embodied. Instead, Mandela inspired a fundamental transition.

Instead of putting retribution first, our country embraced a restorative approach to offenders and their punishment. This demanded that prison conditions respect human dignity. Rather than punitive detention only, our Constitution promised a system of corrections grounded in human rights. No longer would prisoners be discarded as irredeemable burdens. Instead, they would be treated as people worthy of respect and rehabilitation. The correctional services statute enacted in 1998, while Mandela was President, eloquently embodies this approach.

More than two decades later, reality is more harsh. South Africa has one of the highest rates of imprisonment in the world. Worse, our re-offender rates are also as worrying as they are high. As our policies have become more punitive, our crime rate continues going up. In other words, harsh punishments aren’t working to keep our communities safe.

Our correctional centres are badly overcrowded. Sometimes desperately so. We force our correctional centre staff in some instances to cram three times more inmates into cells than intended. This may mean sleeping on the floor, in unhygienic conditions, with below-par ablutions.

Why the overcrowding? Because, at the very time we enacted a humane and sensible statute (from prisons to correctional centres, and prisoners to inmates), we also changed our criminal laws. We made them harsher and much more punitive. More crimes, more offenders, more custodial time.

Since 1995 the number of people in our correctional centres has increased by two-fifths (39%). About one-third of all detainees are not even convicted – they are awaiting trial.

In 1994, only 400 prisoners were serving life sentences. That number has ballooned monstrously. Today, nearly 16,000 prisoners are serving life sentences.

The correctional statute has high ideals. But the fearful truth is this: our correctional centres contribute to rather than ease our crime problem.

The judicial inspectorate, which I’ve headed since January 2020, was established to inspect and report on correctional centre conditions. The inspectorate has strong powers of investigation. Deaths, mechanical restraints, use of force and isolation of inmates must be reported to it.

Just weeks after I took office, the inspectorate visited Zonderwater prison near Pretoria. In many respects a model institution, it seemed well-run and smoothly-functioning, with an experienced corrections officer, Mr Baloyi, at its head.

Zonderwater boasts a dairy farm, chickens in barns (not cages) and huge hectares producing tons of vegetables and fruit, not just for its own consumption, but for the whole region. It even has its own functioning sewerage treatment plant.

With rightful pride, officials took us to their production workshops. These should be the heart of any centre. The head is the hugely experienced Mr Rulashe. Spread out over several acres, his workshops train offenders in woodwork, metalwork, upholstery, signage, and printing. Every day, Mr Rulashe, through discipline, focus and practical training, helps prepare learners for their release – so that they can return to their communities and participate in building our society.

But there’s a dark side. The correctional services budget undervalues the acute potential of programs like these. Zonderwater workshops are operating at less than half their capacity. Out of 62 staff members needed, Mr Rulashe has only 28. He pointed to a number of classrooms he had to shutter. Why? Because the department did not fill the teaching posts, for nationally accredited diplomas.

Mr Rulashe has the skills and the will to double the number of inmates he turns into carpenters, metal-workers and printers – but his qualities are not matched by budgeting clout and political follow-through.

Recently I briefed the parliamentary portfolio committee. MPs swiftly matched Zonderwater under-utilised rehabilitation facilities and programs with their own stories, from across the whole country.

Taunting our country’s humane and sensible vision of criminal justice, our correctional facilities are quickly growing increasingly dangerous. They stand as reminders of how hard it is to heal from the violence of our past.

There is a sustained focus on incarceration over rehabilitation. This is not what corrections personnel choose. It is our choice – we, you and me, the public, and our representatives in Parliament, who in our name enacted ever-harsher, ever more futile punishments and crimes. We have crammed our correctional centres and blocked the avenues of rehabilitation and reform.

There’s more. Overcrowding means that sexual assault and other violence is widespread. The conditions are fertile for communicable and infectious diseases. And mental health is a grave concern. Are these conducive spaces for rehabilitation, or pointless and punitive institutions?

Even an ideal correctional system requires external oversight. In our increasingly creaky system, mandatory reporting is indispensable. This is for two reasons: to ensure accountability, and to provide early warning if big trouble is on the way.

The correctional services statute is clear about what it demands. Every single death, natural or unnatural, must be reported to the inspecting judge. Every use of force must be reported. Every time an inmate is put in solitary confinement or shackled with mechanical restraints, this must be reported.

But over the last few years, the reporting system has fallen into shambles. Compared to 2018, the year 2019 saw a stomach-churning plunge downwards in the number of incidents reported.

In some cases, the decline is as high as 84%.

Obviously, mandatory reportable incidents are severely underreported.

We now have assurances from the department that a new system, E-corrections, will resolve these problems. We hope it will quickly become operational and deliver all it has promised.

If not, we risk a surge of institutional violence that may shock the conscience of our country. Already, the warning lights are flashing. This is not good for inmates, or for the personnel we employ to guard them, often at great personal risk. Nor is it good for our society.

Our law envisions a carceral system based on human rights and dignity. We are struggling to fulfil its standards; but there is hope.

There is hope in the work of Mr Rulashe at Zonderwater, in the work of people who dedicate themselves to trying to open paths for inmates, thereby securing our society’s future.

But a functioning correctional system requires not only well-trained, honest, and disciplined personnel; it requires proper oversight. And it requires a proper budget. We need to do far, far better with both.

Views expressed are not necessarily GroundUp’s.