25 February 2025

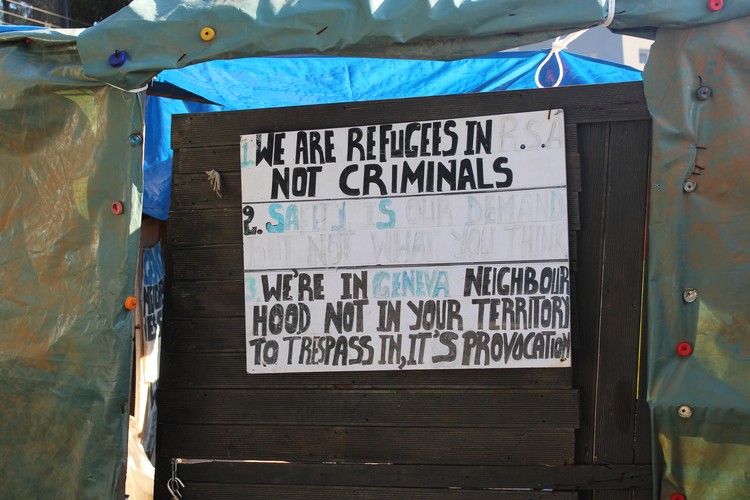

Spouses and children of asylum seekers are struggling to get recognition from Home Affairs. Archive photo: Kimberly Mutandiro

When rebels invaded his home in South Kivu in the Democratic Republic of Congo in 2002, killing many people, Kabamba Mukinayi fled to South Africa rather than be forced into the army. He applied for asylum at the Cape Town Refugee Reception Office and was granted refugee status within a few months.

His wife, Tshilobo Tshiamakanda, followed him and applied for asylum in Musina before joining her husband. When her permit was due to expire, they went to the Cape Town refugee office and applied for her to be joined to her husband’s status. She thought she’d automatically receive the same status as her husband. But 23 years later, she is still in limbo.

In June 2019, the Western Cape High Court handed down a landmark ruling granting access for spouses, children and other dependents of asylum seekers and refugees to be able to document themselves in South Africa under “family joining”.

Family joining means granting refugee status (or a similar secure status) to family members “accompanying a recognised refugee”, according to the Refugee Rights Unit at the University of Cape Town’s Law Clinic.

The ruling followed an application brought by the Scalabrini Centre on behalf of families of refugees who were facing arrests and detention because of documentation issues.

Tshiamakanda has submitted her Congolese marriage certificate several times but to no effect. She has had to endure decades of short-term and inconsistent renewals at the refugee office. She has had numerous interviews, yet her case remains unresolved. Without clarity on her status, she struggles to open a bank account or access other services. She freelances as a child carer.

“We are a legally married couple. All I want is for my wife to join my status so that her life can be easier,” says Mukinayi.

Several couples GroundUp spoke to at the refugee office are in similar situations.

Some said their files were lost during the closure of the Cape Town refugee office in 2012. The new office opened in 2023. Those who had applied at the Pretoria and Durban refugee offices tried to continue their applications in Cape Town, but they say the system couldn’t pick up their family joining files.

A Kenyan couple, who wished to be anonymous, say they have struggled for years to have their papers joined. The husband belonged to an ethnic minority that faced targeted attacks during post-election violence in 2008. His family’s home in Naivasha, about 90km from Nairobi, was burned down during clashes when the police did not intervene.

After receiving threats, he left Kenya and applied for asylum at the Musina Refugee Centre before moving to Cape Town.

In 2011, his wife joined him and also applied for asylum and to be documented with her husband. But before her case progressed, Home Affairs closed its Cape Town office in 2012.

The Western Cape High Court ruled that the closure was unreasonable and irrational in 2012. Home Affairs was ordered to re-open the office by the High Court in 2016, and again by the Supreme Court of Appeal in 2017. The department then sought leave to appeal from the Constitutional Court, but the application was denied.

Since the office reopened, the couple have made countless trips to Home Affairs, submitting applications at the office and online, attending interviews and waiting in long queues, only to be met with rejection, delays and silence.

To date, she has no papers and his permit has since expired. Because of the hostility he faced, he is now afraid to go and renew his permit again.

“They told me to wait for my family to be recognised, and before I knew it, I had overstayed,” he said.

“Every time we go to Home Affairs, it’s the same thing: missing documents, system errors, come back next week, next month, next year. But nothing changes,” said his wife.

The couple was told that their Kenyan marriage is not recognised in South Africa. Their daughter, now 13, has no birth certificate, is currently out of school, and is facing an uncertain future.

Attorney James Chapman, head of advocacy and legal advisor at Scalabrini, said the 2017 court order and 2018 ruling were meant to make it easier for dependents of asylum seekers and refugees to be joined, but families are still struggling.

“There is nothing that should prevent an individual recognised as an asylum seeker or refugee and has supporting documents from, by appointment at Home Affairs, joining their family. What happens in theory is that you approach the refugee reception office on the appointment date given by Home Affairs, and you bring all documents. If you don’t have supporting documents to prove your relationship, Home Affairs won’t proceed,” said Chapman.

He said the Scalabrini Centre had handled cases where the files of children who turned 18 were routinely separated from their families’ files, had to file for asylum again, and were then rejected. He said Home Affairs had now confirmed that file separation would only happen upon termination of dependency or upon request, not upon reaching 18. Those separated would still continue to benefit from the claim of the previous file holder.

“There is also a problem that … customary marriages are not being recognised. If you got married by customary law, say in DRC, they [Home Affairs] are not accepting those marital relationships. Only civil marriages concluded are accepted.”

He said in some cases, to join children, Home Affairs demanded DNA, “which is prohibitively costly”.

“DNA is even asked for in cases where parents have birth certificates from their country confirming the family relationship. Where the child is old enough the child should also be able to confirm the relationship without the need for DNA testing.”

Chapman said the Scalabrini Centre can be contacted for help.

GroundUp has waited for two weeks for comment from Home Affairs.