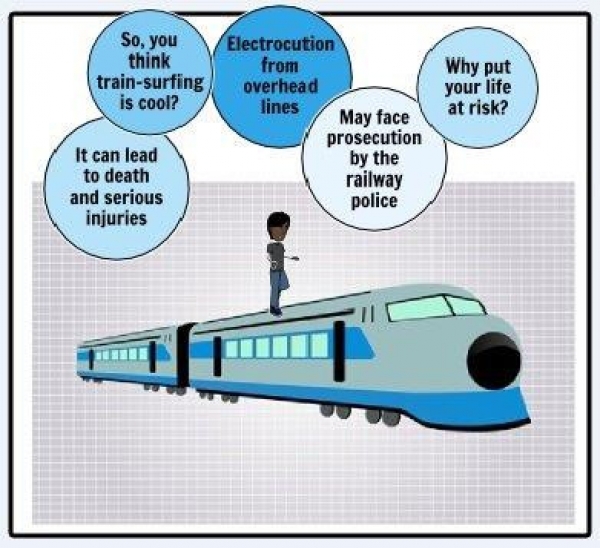

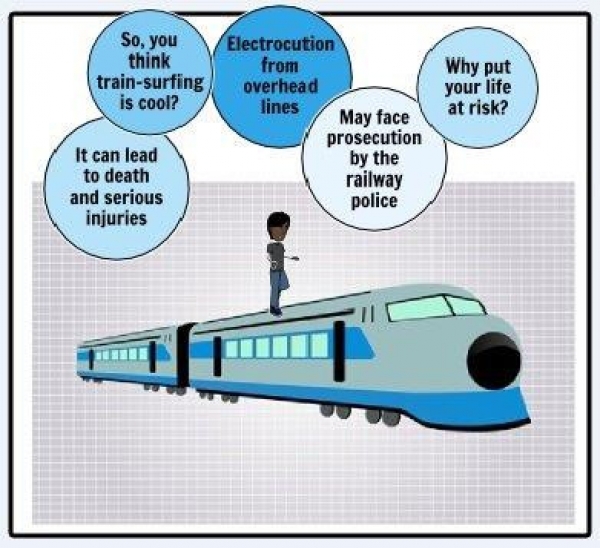

Metrorail cartoon aimed at discouraging train surfing.

9 April 2015

Whiteboy and Tupac are chilling on a bench in New Canada station before their usual high-octane commute to school. Whiteboy, aged 18 and in grade 11 at a former model C school in Jozi, wears a striped T-shirt, shorts and brown suede shoes. He’s smoking Dunhill Courtleigh blends. His “macala” (friend) Tupac is a year younger, with short hair, neat in school rig and black toughees (school shoes) with red laces, high as a kite on weed, with sleepy red eyes. Their excited schoolgirl fans can’t wait to see the action.

The boys are train surfers on the Soweto to Jozi Metrorail. Whiteboy, a master of the bhegos (a backwards-running move in platform surfing) with a top rep to preserve, started surfing in primary school when he was 12.

“My classmate Lucky introduced me to surfing and now I have my own students,” says Whiteboy. “Surfers have decided to ban me from performing on the platform because I am too good. They prefer to see me do the matrix on top of the train.”

Surfing Soweto: a documentary by Journeyman Pictures from 2011 with astonishing footage of boys train surfing in Soweto.

It was on top of a train that 15-year-old surfer Ayabonga Mphoso was electrocuted in February while commuting to school from Khayelitsha to Cape Town. After the train left Philippi station there was a loud bang. The train came to a halt and the grade 8 boy’s body was found on the carriage roof, reportedly with his school books beside him.

There’s a high risk in all train surfing moves. In platform surfing there is isipharaphara, where you hop in and out of a moving train, hands grabbing hold of the steel bar on the train door. Even more dangerous is Whiteboy’s backwards specialty, the bhegos.

Train surfers Whiteboy and Tupac chilling at New Canada Station with some of their fans. Photo by Mosa Damane.

The matrix is performed on the carriage roof of a moving train, and involves bending backwards to avoid deadly overhead electric cables and girders. There are rules of etiquette: beginners climb to the roof from the space between carriages, veterans take the harder route from a carriage window – both while the train is in motion.

Then there’s the gravel, running along the rail rocks next to the sleepers hanging on to that steel bar; and the tsho dlozi (swinging outside a moving train with the doors closed, hands holding tight on the train’s roof edge).

At New Canada station a train arrives on platform 3 and as it pulls out Whiteboy and Tupac swoop, one grabbing a door while the other does side surfing with isipharaphara. They let go when they realise the train is not heading for Jozi.

“It’s a pity I’m wearing my school shoes today,” says 17-year-old Tupac. “I wish you could see me rocking my black 35s (All Star takkies). Ngiyashisa kabuhlungu kabi! (I’m too hot!).”

He says Whiteboy taught him the basics of surfing.

“In 2010 I was very shaky, but now I can do all the tricks. I don’t get a thrill from riding unless I’ve smoked a joint.”

Train surfing has been going on for years. A decade or so ago surfers bonded in violent gangs which terrorised schoolkid commuters and graduated to lives of crime. These days gangs are largely gone and the tough guy image has mellowed, with surfing practised for fun, thrills and status.

“In the morning at 7am we all gather for a joint before surfing trains that come and go from different areas,” says Whiteboy. “My favourite place is the Croesus curve towards Langlaagte station, where spectators get to see me do “gravel*.”

Whiteboy doesn’t think about death when he’s surfing, only about getting his moves right. “I don’t focus on the crowd that much either. I keep myself safe by focussing on making the right moves and grips. When the security guards do a stop and search for illegal commuters and surfers I climb on top of the roof and no one will come after me. They are scared of the voltage and it’s my game – catch me if you can!”

Finally train 9334 arrives and departs for the classroom with Whiteboy doing a spectacular bhegos while Tupac hitches in and out of a carriage door with isipharaphara.

Like old soldiers, train surfers who escape the morgue just fade away. Sonic, former member of the once feared Rough Riders gang, is now 31, living alone in a two room shack in Mzimhlophe, selling sweets and snacks to make ends meet.

Back in 1995 Sonic was only 11 when his friend Sisqo introduced him to the “cheesy” life of train surfing and he vividly remembers his first journey on train number 9323.

“We boarded at Mzimhlophe station and on our way to Mjibha (Joburg) pupils started changing their uniform and wore jeans that were hidden inside their school bags,” he says. “Girls put on make-up and lipstick. I was attracted to this fast life in the train: boys surfing, smoking, and beautiful girls screaming and cheering those who surfed all the way to Jozi.”

That day in Jozi they moved on to Moonlight, a club not far from the taxi rank, where Sonic had his first beer and smoked his first cigarette, to be part of the crew. “We spent the whole day dancing to dope and loud house music,” he says. “On our way home the gang mugged anyone who happened to be in the way. I mugged a skinny boy and took his cash and belongings.”

“Zile, the big boss of the Rough Riders, was impressed with what I did and I was welcomed as a member of the gang because of what I did to that poor skinny boy. I was under the influence of alcohol when I did it, but it became a big deal for Zile.”

“I learned a lot of stuff as a Rough Rider: invading a platform full of pupils like hyenas in search of the weakest victims to rob. A single hot klap made things easier. We would surround a group of coconuts on the platform and take all phones and money. No one would come after us, even those who knew us from Mzini (Mzimhlophe) where we come from.”

Sonic got his nickname because of his speed when platform surfing. “I twisted my right hand on Dube platform 3,” he says. “I was high on benzene, missed my step and flew like a jet before landing on my hand. Tjo! Damn! On that day I banned benzene for life and stuck to alcohol and zolo (weed).”

In February 2002 Sonic, then 18, was arrested with other Rough Riders for one of their train robberies. He spent four years in prison, two of them at Diambo juvenile prison in Krugersdorp, which he describes as “a small heaven, we ate seven colours (tsotsi taal for Sunday lunch) every day and watched DStv”.

Another old soldier is Spider, now 26 and one of the few train surfers who got electrocuted by an overhead wire – and lived to tell the tale.

For Spider it started when he was 13 and in grade 8 at Anchor Comprehensive high school in Orlando West. “My heroes were the Amaroto (Rats) gang and their spharaphara (hopping) moves on the trains,” he says. “I didn’t hesitate and was quick to show on my first ride to Macanas (New Canada station) that I am brave and ready to be a member.”

Retired train surfer Spider: electrocuted and living on R1250/month disability grant. Photo by Mosa Damane.

Train number 9323, known to the Rats as the school bus, carried schoolkid commuters only – no adult would brave the mayhem. “For booze and drugs we mugged cheese boys and girls (kids with rich parents), those with expensive phones and bags,” says Spider. “Our favourite treat was vodka and pap sak (cheap wine) and we enjoyed surfing under the influence of alcohol and drugs.”

A girl nicknamed Mum Rider joined the Rats. She was a 16-year-old grade 11 pupil at Langlaagte Technical High School and Spider remembers her as “very beautiful and full of drama, like a gangster.”

Mum Rider carried a silver flick knife and Spider had a thing for her, but found her too intimidating. “She was a pacer, demon fast on the platform with magic and pace in her feet.”

Spider’s career as a surfer ended in 2004, when he was 15 and still a young Roto (Rat). “It was Friday afternoon around 2.45 and my gang was on fire, high on drugs and drink. I vividly remember climbing on top of the train and bracing myself for the matrix stunt. What happened after I don’t remember at all.”

The high voltage shock cost Spider two broken ribs, two front teeth and the loss of the use of his right hand. Today he lives with his parents in Orlando West, wears a cap to cover his scary scalp wounds and draws a disability grant of R1,250 a month.

Spider’s scar from being electrocuted. Photo by Mosa Damane.

His surfing friend Madrugs lost his right arm after a voltage shock.

Today Spider says he would like to work for Metrorail, educating young commuters about the perils of train surfing.

“My message to those who are still surfing is simple: I know you feel like you own the world, but the end result is not funny – you either die or get disabled for the rest of your life.”

So how many lives does train surfing claim? It seems the authorities don’t know or aren’t saying. An obliquely-worded indicator is to be found in the latest State of Safety Report by the Rail Safety Regulator, SA’s custodian of railway safety, presented last November. The Regulator, whose function is to investigate all railway accidents, records 16 deaths from “electric shock” on the tracks during the year ending 31 March 2014 – double the previous year’s total and a cause for “concern”.

The 16 fatalities, the report states, “does not exclude those individuals who are train surfing”. So how many of the 16 were train surfing? The Regulator’s reports over the past six years reveal a total of 83 fatalities in the electric shock category. How many of those deaths were from train surfing?

And train surfers don’t just die from electric shocks. They fall off carriage roofs, get crushed by train wheels and perish from a host of mishaps. So of the total 456 rail fatalities from “operational occurrences” in 2014, how many were from train surfing? And how many of the total 2,701 fatalities over the past six years?

We are waiting for a response to these questions from the Rail Safety Regulator CEO Nkululeko Poya.

In April 2014 Prasa Rail CEO Mosenngwa Mofi (the Passenger Rail Agency of SA consolidates passenger rail entities including Metrorail) revealed that 17 of 238 rail fatalities on its networks in 2013 were from “people falling while hanging outside the trains or vandalised train doors.” Metrorail security services, said Mofi, had been put on high alert. “We will arrest and prosecute anyone caught hanging on the outside of the train.” The arrest threat could have been aimed at train surfers, but were there surfers among the 17 fatalities?

“I don’t have death figures of train surfers,” says Metrorail Gauteng spokesperson Lillian Mofokeng. “We have safety campaigns that are held randomly. Every Friday we choose a school or station for our commuter educational programme. Metrorail has managed to arrest some of the surfers, but most of them are as young as 14, and we can’t charge a minor who is badly injured and needs medical attention.”

As for arresting them, “train surfers are too good for our security guards,” admits Mofokeng. “Guards are not trained to chase people on the roof of a moving train.”

Riana Scott, spokesperson for Metrorail Western Cape, said there have only been three incidents of reported train surfing on the Cape Town network in the past two years, including the fatality in February. “It’s not something that’s very prevalent in Cape Town, probably because we have the sea and people can do real surfing. And these three incidents were only alleged to be train surfing – people continually ride on top of the trains.”

Train surfing first emerged as an extreme activity among township youth in South Africa during the 1980s. The craze spread to Brazil, with an AP story out of Rio de Janeiro in 1988 reporting 150 train surfer fatalities the previous year, with hundreds more injured and the government company that ran commuter lines paying out $700,000 in death and injury claims.

In the 1990s it became popular on Germany’s S-Bahn rapid rail system; one crew leader known as the Trainrider found notoriety surfing the 320 km/h Inter-City Express. In 2008 train surfing reportedly claimed the lives of 40 German teens.

In Russia it has become an extreme sport known as Zatseping, with numerous videos posted on YouTube. Surfing in Russia reportedly claimed more than 100 teens dead or seriously injured in 2011.