12 May 2025

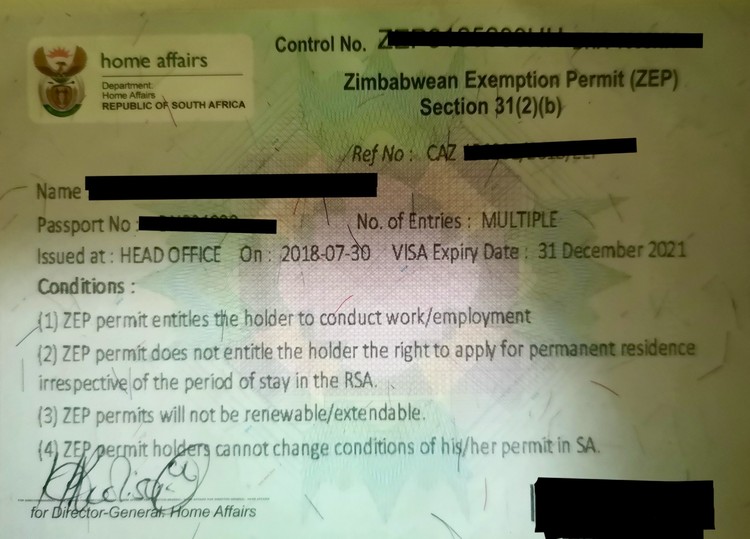

An interdict protecting ZEP holders is being challenged in the Supreme Court of Appeal. Archive photo: Tariro Washinyira

The legal saga over the Zimbabwean Exemption Permit (ZEP) returns to court on Tuesday as the Supreme Court of Appeal (SCA) hears the Department of Home Affairs’ appeal against a ruling that temporarily protected ZEP holders from arrest and deportation.

The interim interdict, granted in June 2023 in a case brought by the Zimbabwean Immigration Federation (ZIF), shielded all ZEP holders — about 178,000 people — while the legality of the permit system’s termination was being challenged.

The validity of the ZEP was last year extended to November 2025.

The Department of Home Affairs is asking the SCA to set aside the interim relief granted to the ZIF, effectively reinstating the department’s ability to enforce immigration laws against ZEP holders until the wider legal questions around the permits are resolved.

In its court papers, the Department of Home Affairs argues that the matter should be considered moot because there’s already a separate high court ruling, in a case brought by the Helen Suzman Foundation, that declared the minister’s decision to end the ZEP system unlawful and set it aside. The department is also appealing that ruling.

According to the department, the permits were always meant to be temporary and subject to the minister’s discretion. It argues that requiring the minister to maintain the ZEPs until Zimbabwe’s economic conditions improve would amount to an indefinite obligation not supported by the law.

In response, the ZIF argues that the department’s appeal fails to take into account the severe human consequences of terminating the ZEP system. These consequences go to the heart of constitutional rights and cannot simply be brushed aside.

The ZIF argues that it is common cause and undisputed that “ZEP holders would likely be deported in the absence of an interdict preventing such deportation” and that “for ZEP holders that are married to South Africans there would be a breakup of families in violation of their rights to family life and dignity.”

They contend that even without deportations, the sudden shift from lawful residency to undocumented status strips permit holders of basic protections. It places jobs, access to education and family stability at risk and opens people to the daily threat of arrest, harassment, or detention.

ZEP holders face irreversible harm, the ZIF argues. Many would not qualify for any other visa, despite having lived, worked, and built families and businesses in South Africa for over a decade.

These are not hypothetical concerns, they say. When the ZEP system was initially terminated, thousands of people were left scrambling to apply for exemptions they were unlikely to qualify for, with no realistic chance of their applications being finalised in time. That uncertainty continues to this day and remains a real and ongoing threat to livelihoods, safety, and dignity.

They claim the department relies on technical arguments to justify ignoring these impacts, but that doesn’t excuse the abrupt and damaging way the policy was ended or the lack of meaningful alternatives for those affected.

The ZIF also rejects the department’s claim that ZEP holders could have applied for other visas instead of relying on court protection. They argue that these alternatives were either unavailable, impractical, or too slow.

The ZEP scheme was created precisely because most permit holders did not qualify for mainstream visas and the department admitted as much in its own court filings, they argue.