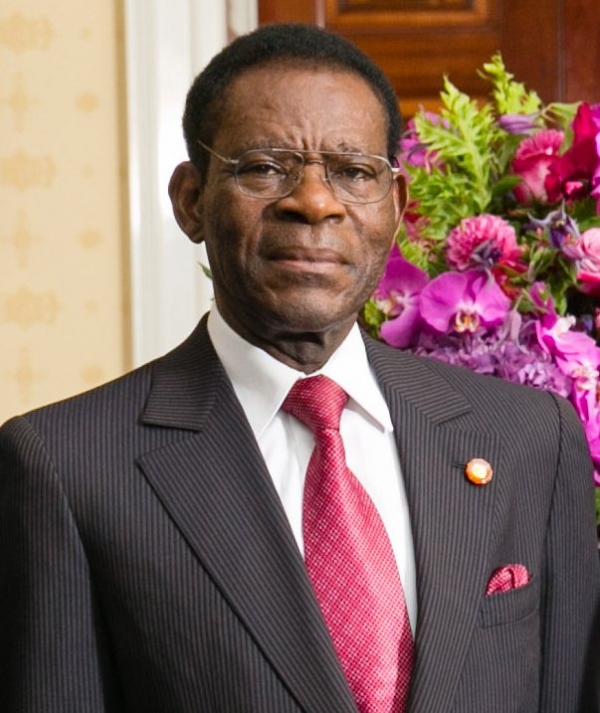

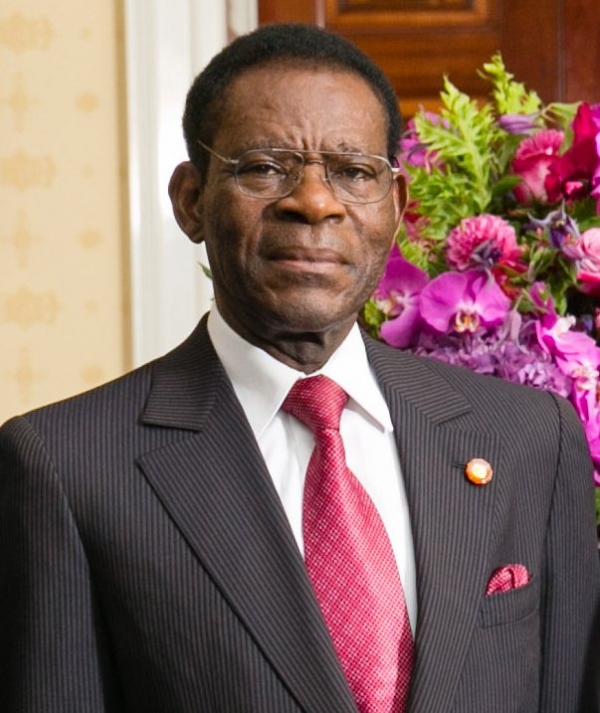

Teodoro Obiang, who been president of Equatorial Guinea since 1979. Photo by Amanda Lucidon. Licensed under Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

19 January 2015

The brutal kleptocracy of Equatorial Guinea hopes to gain a measure of international acceptance by hosting the African Cup of Nations (Afcon) soccer spectacle that kicked off this weekend, writes Terry Bell. The oil and gas wealth generated by this “Kuwait of Africa” provides the economic wherewithal for the ruling elite to buy favours while the bulk of the population wallows in repressive poverty. Bell was the only foreign journalist to cover the independence of Equatorial Guinea more than 46 years ago.

There was little fanfare in Equatorial Guinea in October 1968 as that country celebrated perhaps the shortest independence handover in history. I know because I was there. By a combination of bad luck and equally bad judgment, I and my partner, Barbara, were stranded for three months on the island now known as Bioko, that houses the capital, Malabo.

With independence looming, the Spanish authorities had placed a ban on visitors shortly after we landed. As a result, I was the only journalist and, apart from some Mobil oil and of Red Cross workers, we were the only foreign visitors on the volcanic island that, together with a clutch of smaller islands in the Bay of Biafra and a sliver of the mainland sandwiched between Cameroon and Gabon, makes up the tiny state of Equatorial Guinea.

It soon became obvious why the authorities of what was then still fascist Spain had decided not to have an open door policy for independence: the tension hung as heavily in the air as the intense humidity. This malarial African toehold of imperial Spain, lying almost squarely across the equator, was coming of political age with a legacy of brutality and neglect.

It had only been accepted as a colony in 1959 and was, even by then, a drain of the Spanish fiscus. Equatorial Guinea’s cocoa-based economy had all but collapsed and exploratory oil wells had, at that stage, turned up dry. The Spanish dictator, General Francisco Franco, decided to give in to calls for independence and started belatedly to provide more education and training for Guineans.

These locals, often hastily trained to take over as bureaucrats and police, openly expressed their loathing of the Spanish. Fearful Spanish colonials reacted by sending wives and children back to Spain and stocking up on provisions in fortified homes. Weeks before independence day the local gun shop — it supplied weapons and ammunition almost exclusively to Spanish citizens — reported having sold out of all arms and ammunition.

Around the airport, south of the capital, used by the Red Cross to fly in aid to then beleaguered Biafra in the dying days of the Nigerian civil war, Spanish soldiers watched wearily from behind sandbagged machine-gun posts. Members of the feared “black Guardia” — the political police of fascist Spain — regularly made their presence known in bars as pre-independence elections were held.

But the elections came and went without incident and were won resoundingly by a local strongman Francisco Macias Nguema, known as El Gallo Rojo (The Red Rooster). Like his opponent, Atanacio Ndongo, Macias was a member of the Fang community from the mainland, originally brought to the island by the Spanish to help subdue the rebellious islanders, the Bubi.

The manner in which the elections were held was controversial and it was said that most Bubi had boycotted them. The only factor unifying Bubi and Fang seemed to be hatred of Spain and the Spanish.

We got to understand this because we had arrived in Equatorial Guinea on a Spanish supply ship on its regular, fortnightly run. Travelling third class with several Spanish navy conscripts and returning Guinean students, gave us some background. It also proved a boon in that we made contacts, especially among local residents when we landed. We spoke very poor Spanish, but we were accepted as South Africans in exile.

So it was that we made our way, almost certainly the only foreigners present, with Guineans we had met, to the traditional flag lowering and raising ceremony. It was to be outside the governors’ — soon to be presidential — residence up the hill from the town that clustered around one side of the rim of the sea breached extinct volcano that is the harbour.

That afternoon of 12 October 1968 was overcast and sticky as we stood, with a crowd of several hundred Guineans, across the square from the whitewashed residence, facing a nervous-looking honour guard of rifle toting Spanish sailors in dress whites. The tension seemed just as palpable as the humidity that hung like a moist blanket over everything.

To a cacophony of boos, the sailors presented arms as the Spanish flag was lowered and, then, to ragged cheers, the new flag of Equatorial Guinea was raised. That was it. The flag lowering and raising signalled end of more than 200 years of Spanish colonial rule and the birth of Africa’s then newest state. A gold braided officer barked an order, the sailors turned and marched off down the slope toward the harbour where their grey-painted ship lay at anchor.

It took some time for the small crowd gathered in the square to realise that nothing more was going to happen. Then, in ones and twos or small groups, we began to disperse, moving down the hill through the deserted streets of the dilapidated capital. The shutters on all the shops, homes and businesses were tightly shut. It was eerie, but not unexpected.

Oil company and Red Cross officials had instructed their employees to stay home behind locked doors. Long-time resident and honorary British consul, Sydney Dunn, the sole diplomatic representative on the island, also announced the day before, that he would shut up shop.

Dunn, the managing and only director of the Ambas Bay Trading Company, the last colonial outpost of the Lever conglomerate, locked and barred his office and warehouse and retreated with his wife to his fortified house on the cliffs overlooking the harbour and the capital. Another anti-climax was about to be reached.

The only activity was in several bars in the back streets where locals celebrated independencia with often blood-curdling threats about what would be done to those Spanish who remained on the island. Most said they had voted for Macias, but few seemed sure how good a president he would be. The consensus was that anything and anyone would be better than what had gone before.

Life returned to a form of tense normalcy in the succeeding weeks. Although Equatorial Guinea had become the world’s newest state, the international postal system and a bank in London still seemed unaware of its existence. But finally, we were able to leave. From a secure base in Zambia we stayed in touch with events in Malabo which seemed to involve several summary executions. Ndongo, the one-time challenger of Macias who had become deputy president, also died a reportedly horrific death, at the hands, it was said, of Macias. A colonial tyranny had given way to a homegrown one.

But Macias himself came to a sticky end in the wake of a military coup in 1979, led by his nephew and still president, Theodoro Obiang Nguema Mbasongo. A political opposition developed and was brutally crushed, with several of its leaders fleeing to Spain. One of them, Severo Moto, is accused of being behind the abortive mercenary coup led by Simon Mann.

In 1995, the initial assessment by US oil giant Mobil that there were “no commercially viable offshore oil deposits” in Equatorial Guoinea was proved spectacularly wrong. Huge deposits of gas and oil are now being exploited and this former backwater has been referred to — in terms of oil output and income — as Africa’s Kuwait.

However, little seems to have changed for the long-suffering population. But it has certainly changed for the ruling elite. In 2004, for example, allegations of widespread theft of oil revenues were vindicated when it emerged that $300 million (R3.45 billion) had been deposited into a New York bank account where the sole signatory was President Obiang. And in October last year, the president’s son, also Teodoro, paid $30 million (R345 million) in a United States justice department settlement following charges that he used funds plundered from his country to amass assets in the US.

Certainly, the immense wealth that has flowed into Malabo in recent years, has ensured that the Obiang family lacks neither money nor power. What they apparently crave is international acceptance, hence the invitations to various African leaders and the offer to host the Afcon Cup.

The opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author. No inference should be made about whether these reflect the editorial position of GroundUp.