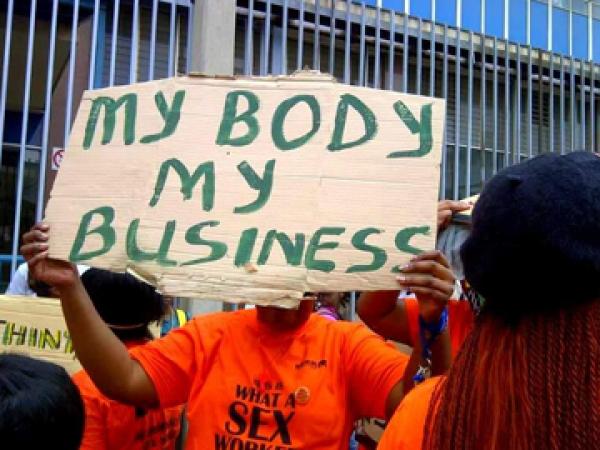

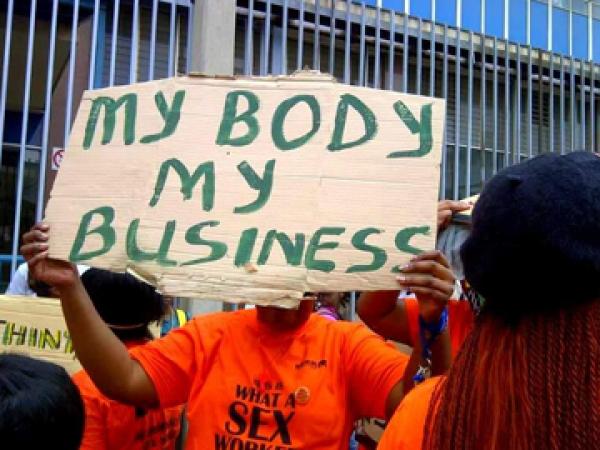

Sex workers and allies march on 3 March 2013 in Johannesburg to commemorate International Sex Workers’ Rights Day. Photo courtesy of Sonke Gender Justice.

23 May 2014

Two recent events brought the question of decriminalisation of sex work into the public eye. The first was the leaking of a draft policy document developed by Amnesty International advocating for decriminalisation of both the buying and selling of sex.

This received strong criticism from those opposed to sex work, such as Nicholas Kristof, who writes opinion pieces for the New York Times.

The second was the vote by European Parliament earlier this year in favour of adopting the Swedish model of decriminalisation of sex work. This model criminalises the purchase of sex, prosecuting clients only.

For those committed to policy reform for sex work in South Africa, these events are significant and will influence the debate on what legal model South Africa should adopt.

The South African Law Reform Commission (SALRC) has previously considered four policy models on sex work in South Africa: full criminalisation, partial criminalisation (the Swedish model would fall under this), legalisation and full decriminalisation. Although supporters of the Swedish model have hailed it as a great success, and as a more ‘woman-friendly’ policy approach to sex work, research has shown that the Swedish model has not been empowering nor has it improved conditions for sex workers in Sweden, or any of the other Nordic countries that have adopted the model.

At first glance, partial criminalisation appears to be a positive move – recognising that people selling sex are not criminals that ought to be punished. The real problem, the model assumes, are the clients who provide the market, driving people into sex work and exploiting and abusing sex workers. It is understood that prosecuting clients will cut off demand, which would discourage people from entering sex work, and allow others to leave.

But the Swedish model is problematic both conceptually as well as practically. While ending the prosecution of sex workers is certainly a step in the right direction, this model focuses on the wrong thing. It ‘demonises’ clients and assumes that people who are willing to pay for sex should be punished. It understands sex work as a social ill, something inherently exploitative, and assumes that sex workers (assumed to all be women) are perpetual victims. The policy, therefore, aims first and foremost to reduce the perceived social ill, while the rights of sex workers form a secondary consideration.

Sex workers making a rational and well-thought-out choice to do sex work are left unconsidered. The fact that the vast majority of sex workers (men, women and transgender people) choose to do sex work because it offers them a viable source of income, and an opportunity for survival in the context of poverty, is virtually ignored. Moreover, the idea that many sex workers are experiencing sex work as sexually liberating, where they can determine the terms under which they have sex, is incomprehensible to policymakers. Sex worker movements and collectives from across Europe and the world have come out against the Swedish model, arguing that a move like this not only limits their autonomy, but also threatens their livelihood.

It should come as no surprise then, that it hasn’t benefitted Swedish sex workers. Along with threatening their source of income, partial decriminalisation has worsened working conditions. Unlike previously, where there was no explicit prohibition of sex work, many people now are forced to work in unsafe or remote locations so as to avoid their clients getting arrested, which makes the negotiation of safer sex more difficult, and exposes them to a greater risk of abuse or exploitation by clients.

It has failed even by its own metric of reducing sex work and trafficking. Neither the incidence of trafficking, nor the demand or supply of sex work has decreased in Sweden in the 13 years since the model’s introduction. Sex workers in Sweden have repeatedly called attention to the fact that they were not adequately consulted in the policymaking, and that overall, the Swedish model fails sex workers miserably.

What is needed in South Africa, instead, is policy reform which is centred around sex worker rights, one informed by the insights and experiences of sex workers themselves. Considered in this light, full decriminalisation is the policy choice that makes the most sense in the South African context.

In our context, Sisonke Sex Worker Movement – a collective of sex workers from across the country – has been advocating for decriminalisation for years.

One of the greatest challenge sex workers in South Africa are facing is harassment and abuse by the police. Many police officers go out of their way to abuse and discriminate against sex workers, believing the current law gives them the right to rape, beat, and arrest sex workers without intent to prosecute, or detain sex workers indefinitely without formal arrests.

If the Swedish model is introduced, it is likely only to provide different opportunities for police harassment of clients and interference in the livelihood of sex workers. Under a decriminalisation model, however, police are the protectors of sex workers —not their adversaries— and sex work is regulated under existing labour, occupational health and safety laws.

A truly feminist policy framework should empower the marginalised, not further limit their opportunities for survival or agency. It’s clear that the current criminal status of sex work in South Africa needs to be reformed, but we must be careful to choose a policy reform which will in fact be empowering; one which will truly support and protect the rights of sex workers, in keeping with the values of the our Constitution, and reduce the high rates of gender-based violence in our communities.

The authors are with the Policy and Advocacy Development Unit at Sonke Gender Justice.