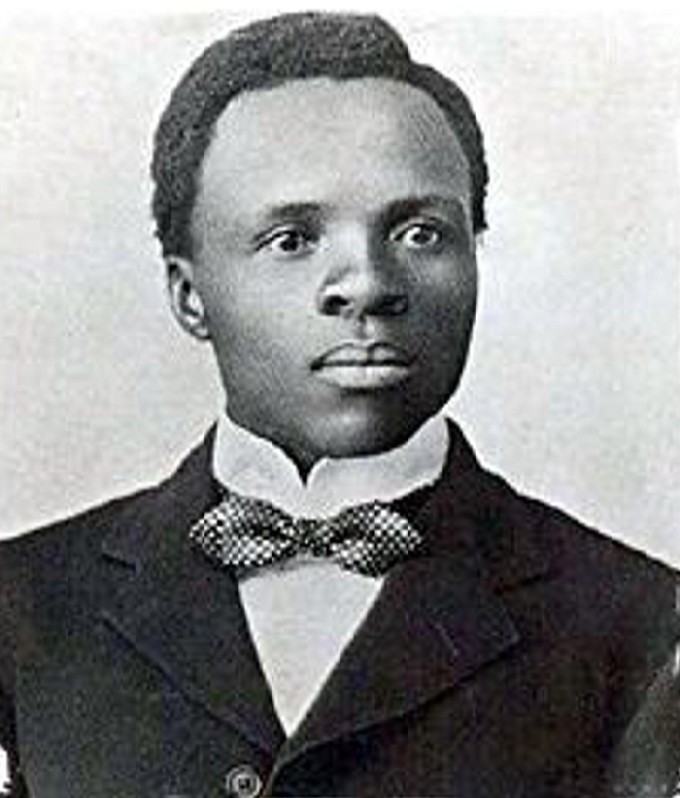

Sol T Plaatje wrote Native Life in South Africa, which describes the effects of the 1913 Land Act. It was described as “one of the most remarkable books on Africa by one of the continent’s most remarkable writers”. Photo from Wikipedia (public domain)

2 June 2016

South African students, and black students in particular, do not readily study history and become historians.

A career in history is not seen as a great job prospect.

African universities invest far too little in studying and writing their own history.

Black historical writing is often encumbered by a tone of historical grievance - collective experience or personal experience. Writing in the mode of grievance is necessary to exorcise the pain of the past and present, but it can also make one stand still and not move the past into the future.

It is on this account, that the American black writer Richard Wright in his essay Blueprint for Negro Writing once wrote: “Today, the question is: shall negro writing be for the negro masses, moulding the lives and consciousness of these masses towards new goals, or shall it continue begging the question of the Negro’s humanity”.

Wright speaks of two forms of black writing: one that looks backward and one that is fully conscious of the past, but wants to engage the project of the future. It is not enough to remind people constantly of black pain without constructing a modern mode of blackness and rewriting the narrative of emancipation that shapes the way we think of economy, democracy, global culture and even non-racialism.

Black writing can take the form of free-off loading - to write thoughts as particular events, incidents or engagements demand. Or it can be more serious - social and historical scholarship digging through archives. The former is easy and the latter is harder requiring dedication and huge economic and personal sacrifice.

We can only admire the political activism and historical work of CL R James, the Caribbean black thinker and writer of a seminal work on the first black slave revolt and revolution on the island of St Dominique, later renamed by the revolutionaries as Haiti.

Long before him, this sort of history and sociology was a project undertaken by the illustrious champion of the scientific recording of black experience, the American intellectual WEB Dubois.

Du Bois was also an admirer, by the way, of Weber, the German sociologist. It is worth mentioning this, as white traditions of intellectual enlightenment are a gift to humanity just as white or European civilisation drew on the scientific, artistic, and technological gifts and contributions of other civilizations. Most of whom happen to be non-white.

Writing about self - either one’s self or one’s people - is to enter an arena of self-examination. This is to come to terms with one’s own existence, first as a person, then in relation to others closest to one, and then to those outside of one’s group. To put experience of life into words is to process the very nature of one’s own existence.

It is, in a way, to own the truth of one’s own existence rather than something written about one’s self through the eyes of others who are totally divorced from one’s world. Self-truths and truths about others can be told through fiction or non-fiction. Wright and Baldwin wrote in both genres, including autobiography.

Some forms of experience cannot be confined to certain types of words and images. They must be freed from the reigning hegemony. Again, it is the question of how one owns one’s own experience of life. How one is able to tell certain truths about one’s life. This is a matter of confidence, good writing and to unpack white stereotypes, not just scream at them.

Black writers in North America have been a great inspiration and impetus for others. WEB Du Bois attempted to compile the first encyclopaedia of black experience. His project was ambitious and he battled to raise the requisite funds from white benefactors, some of whom tried to exercise some degree of influence over the editorial process. Having little support in the US, Du Bois was invited by Kwa- Nkrumah the first President of independent Ghana, to establish and settle himself in Ghana. Both were champions of pan-Africanism.

The newly independent Ghana gave Du Bois the resources to restart the Black Encyclopaedia project. One could regard this as the first inception of what I call the ‘Black Gutenberg’ - this way of creating writing platforms to exercise independence over black experience and writing.

In South Africa we can decry white writing but we have not invested and cultivated social networks that nurture and support black writers.

Yet South African black writing has a long pedigree - prominent names are well known such as Sol Plaatje, I B Tabata, Tengo Jabavu and many others of the older generation. The list of prominent writers is long - Richard Rive, Lewis Nkosi, Nat Nakasa, Es’kia Mphahlele, and many others have shared their world and reflections for all.

Black experience has to also come to terms with the fact that claiming humanity against white racism does not automatically turn the world into a romantic ideal. It means nothing against xenophobia, or tribal, ethnic and other forms of conflict that undo the continental project of African Ubuntu.

Race is not the only problem and the lens through which we see the world is a product of many internal and external virtues and vices. Our common nature should incline us to construct a better world through cosmopolitan virtues, but the path to be beaten in that direction will be painful and hard.Blacks should not leave the enterprise of writing simply to observers interested in the whole experience of black interiority. The challenge of black writing is to build a humanist tradition that is far more profound and transformative than being stuck in discourses of whiteness and blackness, however passionate. Otherwise we will inherit only a binary way of looking at the world and we will be collectively much poorer in understanding and much less able to create a new world.

Views expressed are not necessarily GroundUp’s.

Correction: The article mistakenly referred to Richard Rive as Richard Reeves. Thanks to reader Themba Moyake for pointing this out. The word “contemporary” has also been replaced with “prominent”.