18 November 2020

An explosive 2015 report reveals how the National Lotteries Commission’s chief risk officer flagged key governance issues that have since come back to haunt the commission. Instead of being heard she was hounded out and the report was buried – until now.

A five-year-old internal report into irregularities at the National Lotteries Commission (NLC) “has gone off like a nuclear bomb”, a source at the troubled institution told amaBhungane.

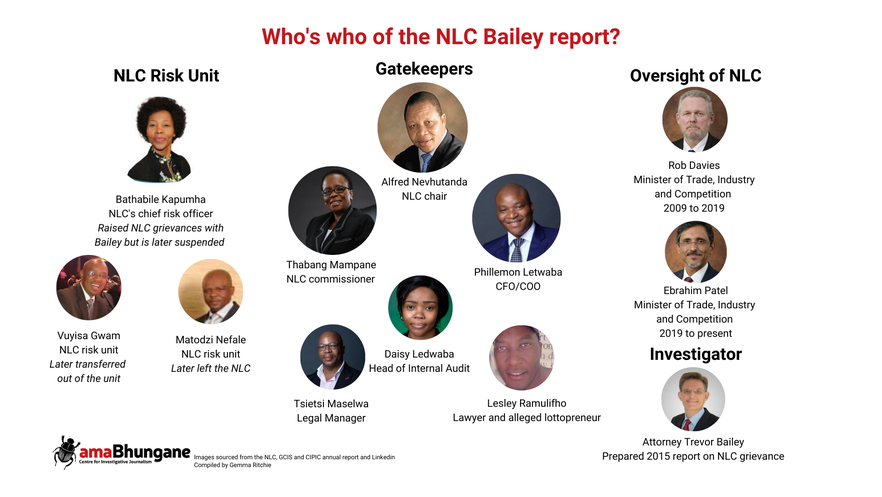

AmaBhungane, which obtained a copy of the report, set off the reaction when we dispatched questions to key players implicated in the report – including outgoing NLC chair Alfred Nevhutanda and chief executive Thabang Mampane (“commissioner” in NLC parlance).

The report, delivered in October 2015 by attorney Trevor Bailey, was the result of an investigation ordered by the NLC’s own board, but was subject to fierce attack by Nevhutanda, largely on procedural grounds, resulting in its effective neutralisation.

The emergence of Bailey’s report is embarrassing for both the NLC and the ministry of trade, industry and competition – led at the time by Rob Davies, but now headed by Ebrahim Patel.

It reveals that both the NLC board and the ministry received early warnings and evidence concerning structural and leadership problems at the NLC that have since blown up in public.

Yet neither the board nor the ministry acted at the time.

GroundUp and the Limpopo Mirror have since exposed numerous abuses of the lottery disbursement process, some of them involving people who were flagged in the report five years ago.

The Bailey report was prompted by a grievance lodged by the NLC’s chief risk officer, Bathabile Kapumha. Her grievance, directed at chairperson Nevhutanda and commissioner Mampane, was supported by two of her investigators in the NLC risk unit, Vuyisa Gwam and Matodzi Nefale.

Kapumha was subsequently suspended and left the NLC. She departed in fear of her life soon after she was involved in an accident apparently caused by her car’s brakes and steering malfunctioning.

In the wake of Kapumha’s departure, Nefale also left and Gwam was transferred to another division, effectively gutting the risk unit.

Contacted by amaBhungane, Kapumha, who had not seen the contents of the report, declined to comment. Nefale also declined to comment, while Gwam could not be reached.

Bailey was tasked to probe Kapumha and her colleagues’ grievances and the NLC’s alleged interference with their investigations.

Bailey, who has served as an acting judge in the Labour Court, found that the grievances “had compelling merit and were justified”.

He recommended the board should consider instituting disciplinary action against Mampane and that the minister should consider acting against Nevhutanda “having due regard to the seriousness of the aggrieved employees’ grievances”.

That did not happen.

Instead, in early 2016 Nevhutanda challenged Bailey’s appointment, his process and his conclusions – and the matter was left there.

But now the report has reemerged at a time when Nevhutanda, whose term expires at the end of the month, appears to be locked in a bitter battle with Patel over the past and future of the NLC.

Just last week, President Cyril Ramaphosa signed a proclamation authorising the Special Investigating Unit to probe alleged corruption at the NLC dating back to 2014, the year when Kapumha’s nightmare started.

At the heart of Kapumha’s grievances were allegations that Nevhutanda, Mampane and others interfered in the functioning and independence of her risk unit, whose job it was to check the applications of potential beneficiaries of lottery money.

The risk unit’s diligence first earned Kapumha and her colleagues praise and then got them into trouble – allegedly when their work led them to investigate powerful or politically connected organisations.

Bailey’s report sets out how in 2013 Kapumha found major irregularities in applications for funds for arts, culture, heritage and environment projects.

The board decided in September the following year to report some 70 projects that were subject to corruption allegations to the police, and cancel the funding of projects amounting to about R320-million. The board congratulated those involved in the checks, including the risk unit.

But not everyone was delighted, it seems.

According to Bailey’s report, there were certain investigations which Kapumha believed ultimately led to her being first rebuked and then suspended.

We deal below with the most important claims and the subsequent fallout.

It is important to bear in mind that Bailey did not conduct a full forensic investigation, but prepared a report of his fact-finding efforts to advise the board on what to do next. His conclusions were provisional.

Also, Bailey’s report did not interrogate why organisations or individuals may have been flagged by the risk unit, and some may subsequently have provided explanations or corrections – so one should not assume they were guilty.

When we put detailed questions to the NLC on 21 October, they replied a week later with an aggressive letter from their lawyers. They eventually provided Nevhutanda’s original response to the Bailey report, given in March 2016, from which we have drawn some responses.

According to Bailey’s report, Kapumha was instructed to remove the Southern African Youth Movement (SAYM) from the list of 70 the board had blacklisted.

Kapumha told Bailey that on a number of occasions she was summoned to meetings with Mampane and Nevhutanda that were also attended by representatives of the SAYM.

Bailey records: “The SAYM alleged that they had supported the NLC during the process which led to the amendment of legislation governing the NLC and the SAYM should not therefore be prejudiced as a result of the irregularities with its application for funding.”

Bailey said the risk unit interpreted Nevhutanda’s intervention to remove the SAYM from the blacklist as some form of “payback” for the SAYM’s support during the process to amend the Lotteries Act.

SAYM executive director Alfred Sigudhla did indeed make a presentation to Parliament in August 2013 that pushed for the NLC to have more influence over beneficiary selection.

Sigudhla is a controversial character, whose organisation is also involved in the community work programmes run by the department of co-operative governance and traditional affairs.

He did not reply to our questions. Organisations linked to him have received over R78-million from the NLC.

Nevhutanda, in his 2016 response, denied he had refused to sign the board resolution until SAYM was removed from the 2014 cancelation list: “I deny the said accusation with the contempt it deserves,” he fumed.

“I also reject with … disgust the suggestion that I forced … some sort of payback to SAYM for assisting NLC in the amendment of the [Lotteries Act]. It is ludicrous in the extreme because I stood to gain nothing from this entire amendment process.”

The NLC has three distributing agencies – charities; sport and recreation; and arts, culture and national heritage – which assess and award grant applications.

The amendments increased the influence of the NLC with respect to the agencies, including making provision for the board not just to respond to applications, but to identify its own chosen projects for “proactive funding”.

And Nevhutanda did not deal with the central claim that SAYM was on the list of cancellations approved by the board, yet was somehow reinstated.

Kampumha told Bailey that during a planning session towards the end of November 2014, Nevhutanda called her outside and revealed that he had received a telephone call from then sport and recreation minister Fikile Mbalula.

Nevhutanda had said Mbalula wanted to know why the NLC was investigating him (Mbalula).

Nexus Forensics, one of the NLC’s forensic service providers, was investigating the Sports Trust, a project the risk unit had flagged.

The Sports Trust received the lion’s share of its funding via the sport and recreation department. But it also received more than R128-million in NLC funding between 2010 and 2018.

It aims to provide sporting equipment, kit and facilities for previously disadvantaged South Africans.

According to Kapumha, Nevhutanda complained that Nexus Forensics was an agent of the Democratic Alliance and it was therefore dangerous to allocate sensitive investigations, such as Mbalula’s projects, to Nexus Forensics.

Nevhutanda then allegedly instructed Kapumha to recall the investigation because his “head was on the block”.

Bailey’s report says Kapumha immediately met with Kgomotso Ngakane who was then Nexus Forensics managing director.

Ngakane told her Nexus Forensics was not aligned to any political party and had even done work for the ANC.

Nevertheless, Kapumha informed Nexus the investigation was being stopped and requested that they return all relevant documents in their possession.

Questioned by amaBhungane, Mbalula replied that he was unaware of any investigation by the NLC against him at all, meaning he could not have complained about it to Nevhutanda. He said it was the first he had heard of it.

In his interview with Bailey, Nevhutanda acknowledged that he told Kapumha that Mbalula had phoned him asking why the NLC was investigating “his organisation”.

But Nevhutanda strongly denied all Kapumha’s other statements concerning the Sports Trust and Nexus Forensics, including that he ever instructed her to withdraw the investigation.

In his 2016 response to the NLC board, Nevhutanda pointed a finger back at Kapumha, arguing that, on her own version, she “was pliable and was willing to compromise herself, her office and the NLC’s reputation by willy-nilly withdrawing investigations”.

Neither Ngakane nor Nexus Forensics would comment, citing client confidentiality.

The Sports Trust told amaBhungane it was not aware of any such incident. In a written response, it said, “The Sports Trust was informed by the NLC about the verification of application of funding received and was contacted afterwards by the forensic auditing company, which was appointed to conduct the verification process.”

It said it had cooperated with the verification and had not lodged any complaint, nor was it aware of the allegation that the minister had complained.

According to what Kapumha told Bailey, a number of other probes were halted at the instance of Mampane or Nevhutanda, supposedly because they were “sensitive and of national importance”.

Kapumha listed investigations into a sports project for the South African College Principals Organisation (Sacpo), into the Kara Heritage Institute, the South African Football Museum, the South African Institute for Drug-Free Sport (Saids) and the South African Sports Confederation and Olympic Committee (Sascoc).

Gwam told Bailey that during October 2014 the risk unit had instructed Nexus Forensics to check up how these entities had spent the funds allocated to them, though there was no evidence presented they had done anything wrong.

Sacpo, an association of technical, vocational education and training colleges (TVET), is recorded as having received a lottery grant of R62-million in 2013 for a sports development project subcontracted to a private company, the Institute of Sport. Sacpo provided amaBhungane with audited accounts showing the grant spending over three years.

Kara is an organisation promoting African heritage founded by MP Dr Mathole Motshekga, who served as ANC chief whip from 2009 until June 2013. NLC records show Kara received a grant of R12-million in 2013. Motshekga did not reply to requests for comment.

The football museum has been mildly controversial because of questions about the value realised from a R7-million grant.

Saids, which drives anti-doping initiatives, received a grant of R18-million in 2013 according to NLC records. The organisation said it was audited by the Auditor General and was not aware of any investigation into its lottery funding.

“No irregularities were … reported to us by the NLC compliance officers,” chief executive Khalid Galant told amaBhungane in a written response, adding that it was possible Saids was flagged because of one of its board members, Dr Harold Adams, also served on one of the NLC’s distributing agency boards.

Sascoc, which has had its own governance problems, is by far the largest single beneficiary of lottery money, receiving about R779-million since 2002. In a response to questions Sascoc said it was not aware of any investigation into its lottery funding. “We were not approached nor are privy to such an investigation,” acting Sascoc chief executive Ravi Govender said.

Back in 2015 Kapumha told Bailey that Nevhutanda was angry and told her at one point she was investigating projects that she should not be investigating – leading her to place these specific investigations on hold.

Mampane and Nevhutanda both told Bailey they never instructed Kapumha not to investigate any person or organisation.

Bailey did not believe them.

In his report he noted, “Although both Nevhutanda and Mampane vigorously denied that they had instructed Kapumha to withdraw investigating allegations of fraudulent activity concerning the above organisations, I am satisfied that the amount of detail and context Kapumha has given, which in some instances was corroborated by Gwam, is sufficient to persuade me that both Nevhutanda and Mampane gave the instructions.”

In his response to the board, Nevhutanda argued this showed Bailey’s partiality: “Notwithstanding how suspect [Kapumha] and her team’s conduct was in this matter, Bailey deemed it fit to accept same wholeheartedly. His conduct in doing so is simply irrational, capricious and arbitrary.”

Yet Bailey’s determination in Kapumha’s favour appears less capricious when considered in the light of the further events leading up to her grievance.

As Nevhutanda’s own evidence was to show, her allegations were entirely consistent with the atmosphere of paranoia that emerged at the NLC in the wake of the risk unit’s attempts to do its job.

Even if the NLC bosses never instructed Kapumha to withdraw investigations, there was clearly a view that the risk unit was exceeding its mandate.

Kapumha told Bailey that Mampane informed her during January 2015 that she intended to establish a committee that would decide which projects should be investigated and those that need not.

This “steering committee” was subsequently established, initially consisting of commissioner Mampane, together with then chief financial officer Phillemon Letwaba, legal manager Tsietsi Maselwa and head of internal audit Daisy Ledwaba.

Letwaba’s insertion is potentially significant, because we now know he went on to become embroiled in allegations involving him and alleged Lottopreneur lawyer Lesley Ramulifho – who also appeared on the scene back in 2015.

The steering committee met monthly prior to Kapumha’s suspension. She was required to present the case database which reflected all reported cases of alleged fraudulent activity.

According to Bailey, Kapumha was unhappy at having to provide the case database because she believed that it compromised the integrity of the investigations and the identity of whistleblowers.

Bailey said Kapumha questioned the motive for establishing the committee and its independence.

There was more.

On 23 January 2015 Kapumha was called into a meeting with Mampane and Letwaba and informed that she would no longer jointly approve projects for payment alongside the chief financial officer. She was not furnished with a board resolution amending its decision to mandate a joint sign off.

Then, at a steering committee meeting on 25 March 2015, Kapumha was informed that Ramulifho had been appointed to conduct a “watching brief”.

His task was to scrutinise the dockets of fraud cases that the risk unit had referred to the Hawks and keep the NLC informed of developments in those cases.

Kapumha told Bailey the risk unit had previously been the contact point for the police and there had been no prior discussion with her of shifting this. Gwam told Bailey that Ramulifho was not even on the NLC panel for legal services.

Given the allegations that emerged later linking Ramulifho and Letwaba, questions remain about the appointment and role of the watching brief.

Ramulifho did not respond to queries.

The background to Ramulifho’s appointment only emerged later, during Bailey’s interview of Mampane for his report.

Mampane told him that on Friday, 27 February 2015, she received a telephone call from Letwaba, who was acting as the commissioner at the time.

Letwaba informed her that a contact from the Hawks had called to warn him about the imminent arrest of a combination of NLC employees, distributing agency members and board members.

Mampane immediately informed Nevhutanda. At a meeting with him the following Monday, also attended by Letwaba and Maselwa, it was decided to employ Ramulifho to conduct a watching brief. This would include communicating with the Hawks and perusing the case files in order to ascertain all the surrounding facts concerning any Hawks investigation relating to the NLC.

The intention, Mampane told Bailey, was simply for Ramulifho to furnish the board with a report concerning the impending arrests so they could “manage the risk exposure to the NLC”.

At the steering committee meeting on 25 March at which she learned of Ramulifho’s new role, Kampumha said Letwaba told her that three lower level NLC officials who had been arrested in 2014 as a result of the risk unit’s investigations were “talking to the police”.

In particular, they were giving the police names and implicating senior NLC employees and board members.

According to Kapumha the steering committee also told her the police had opened a special project to investigate some board members. She said the committee was concerned that the NLC was being “infiltrated” by law enforcement and needed to find a way to mitigate this risk.

Both Mampane and Nevhutanda told Bailey there was nothing wrong with the appointment of the steering committee or the watching brief.

Mampane said it was important that referrals to the police, which could ultimately result in arrests, were done with the prior knowledge of the board.

She told Bailey the steering committee never took formal resolutions because that would have amounted to interfering in the risk unit’s work. Instead, the committee would “share its views” on investigations.

In Mampane’s opinion, the NLC could not have a situation in which it did not know what investigations the risk unit was undertaking and why.

According to Bailey’s report, on 31 March 2015 Mampane informed Kapumha that she had received information from a source that the risk unit team of Kapumha, Gwam and Nefale had earlier that morning attended a meeting with the police – who were about to arrest 18 individuals including NLC officials, distributing agency members and board members.

Mampane added that she had received information from the Hawks that Kapumha had informed them that the chair, Nevhutanda, was a suspect.

Kapumha denied any knowledge of this and said she had been at home that morning because her car had broken down and she had phoned Mampane earlier to inform her.

Later that day the risk unit team were summoned to a meeting in the boardroom attended by Nevhutanda, Mampane, Letwaba and Maselwa.

Kapumha’s version of the events at the meeting are set out in a detailed email she sent to Mampane the next day.

She recorded that Mampane stated that she had not for the first time received a telephone call from the police that they wanted to arrest individuals connected to the NLC. Consequently, Mampane had asked Nevhutanda to intervene at the highest level to protect the NLC’s image.

Mampane accused both Nefale and Gwam of improperly sharing information with the police.

Despite the team’s denials, Nevhutanda said that both he and Mampane knew for a fact that the risk unit team had attended the meeting and Kapumha had lied to Mampane about her whereabouts.

Nevhutanda stated that if he were the commissioner he would have suspended the risk unit team and “better still” would have fired them.

Nevhutanda stated that Kapumha had brought a new culture to the NLC and was turning it into a “police state”.

He said Mampane’s office should write a letter for the risk unit to forward to the police, to withdraw the cases that the risk unit had referred to the police.

According to Gwam’s account, Nevhutanda “started to fume” and said that he had been deployed by the ANC to the NLC to transform the organisation and the risk unit was doing things that went against transformation.

Nefale told Bailey that Mampane’s and Nevhutanda’s tone in the meeting was very aggressive. He felt that their attitude was uncalled for. He pointed out the risk unit’s task was not easy and often conducted in an adversarial environment. Nefale felt that the team should have been given support and guidance for the work they do as opposed to the criticism they received in the meeting.

According to Bailey’s report Nevhutanda did not contest much of Kapumha’s account of the meeting of 31 March.

He acknowledged saying that Mampane’s office should write a letter for the risk unit to forward to the police. Bailey said Nevhutanda believed the risk unit had incorrectly referred the cases to the police and that this could not be done without the knowledge of the minister, Mampane, the board and Nevhutanda himself.

In his 2016 response to Bailey’s report, Nevhutanda went further. “The events of the meeting of 31 March 2015 as indicated were greatly misunderstood and exaggerated,” he said. He denied that he “fumed” or “insulted” the risk unit “in the manner they suggested”.

He said all he and the commissioner required was “proper and lawful channels of communication” between the risk unit, the commissioner, the board and the police about projects singled out for investigation.

He said Kapumha and her team had violated policies relating to confidential information, had “clandestine meetings” with police and had unnecessarily exposed the NLC and its officials to potential reputational embarrassment.

“I still maintain that [Kapumha] sought to introduce a foreign culture… In so doing I did not and could not have meant that criminal activities be swept under the carpet… There is nothing I did wrong and to apologise for.”

That 31 March meeting left Gwam and Nefale very upset. They asked Kapumha to take the matter further.

Kapumha requested a meeting with Mampane, but when her request was deflected she approached the chair of the board risk management committee, Collen Weapond, to intervene.

The dispute remained unresolved and Kapumha decided to escalate the matter to the board audit committee by formally lodging a grievance concerning intimidation and constructive dismissal on 11 May 2015.

She noted: “The utterances that the risk division will be put under administration and disbanded are already being implemented.”

On 25 May Mampane handed Kuphuma a letter informing her she was being suspended for misconduct.

The board decided to proceed with Kapumha’s grievance by requesting an independent service provider to investigate it, leading to the appointment of Bailey.

At the time of Bailey’s report in October 2015, Kapumha was still on suspension. She later resigned.

The report is quashed

In May 2015, Bailey was appointed to interview the involved parties, assess the merits of the evidence and compile a report with recommendations.

His account of his interview with Nevhutanda is instructive.

“As the Chairperson, Nevhutanda sees himself as the head of and embodiment of the NLC. In Nevhutanda’s view, anyone who wishes to know about and/or take information out of the NLC should first approach Nevhutanda because Nevhutanda needs to be aware of any information that leaves the NLC.

“Nevhutanda also sees himself as the ‘go-between’ between the NLC and the Presidency, the Minister, DTI, other government departments and agencies such as the SAPS, SIU and National Intelligence Agency.”

Bailey’s investigation was viewed as an affront and documents attached to Nevhutanda’s response to his report showed the fightback began even before Bailey was appointed.

At a special board meeting on 2 June 2015, the audit committee raised concern that Mampane had suspended Kapumha after she submitted the grievance to them.

Bailey records that, in response, Mampane launched an extraordinary attack on audit committee chair Mathukana Mokoka, alleging that she had forced Kapumha to initiate the grievance.

Mokoka was incensed. She fired off a letter demanding the board investigate the allegation.

In it she noted, “I would like to remind you as the board of how reluctant I was to take on this matter as I suspected how it might turn out given the people who are alleged to be implicated. I was however very saddened and shocked by [Mampane’s] allegations.”

Board human resources committee chair Govin Reddy was dispatched to question Kapumha, who confirmed that the allegations Mampane had levelled against Mokoka were untrue and the grievance was her own doing.

Mokoka, who was not reappointed to the board when her term expired in 2017, did not respond to requests from amaBhungane to comment.

Bailey delivered his report to the acting company secretary on 26 October for onward transmission to the board.

Nevhutanda’s documents reveal that by 19 November that had still not been done.

Adam Cowell, a governance expert contracted to serve on the audit committee and mandated to liaise with Bailey, threatened that if this was not done they would send it on themselves.

On 24 November, he indeed forwarded the report to members of the board, including to Zodwa Ntuli, who had been the department’s representative on the board.

She wrote back to Cowell, noting that she was no longer the representative and providing the email address of the department official responsible for oversight, Jodi Scholtz.

Ntuli noted that the report raised “matters that could embarrass the DTI and the Minister if not attended to” and requested the audit committee to “ensure that the Minister is made aware of this”.

As a result Cowell forwarded Bailey’s report to Scholtz on 30 November.

On 8 December, Scholtz wrote back, copying in Moosa Ebrahim, chief of staff in the minister’s office. Scholtz said the report “raises a number of very contentious issues and seemingly governance infringements” – and she awaited further feedback from the audit committee chair.

It seems there was consternation among some board members that the department was now in possession of the report and there was talk of terminating Cowell’s contract.

However, under the leadership of Reddy and Mokoka the board took up the Bailey report and requested Nevhutanda to respond.

On 14 December he wrote back rejecting Bailey’s allegations and demanding access to all relevant records including “any and all minutes, notes taken, file notes, voice recordings of Mr Bailey’s meetings”.

On 15 February 2016, Nevhutanda delivered an 86-page response (along with 25 annexures) and on 9 March he delivered an additional 11-page argument.

Amid the rebuttals already mentioned, Nevhutanda alleged a conspiracy, saying Bailey “appeared to have been a hired gun to serve the interests of those who intended to destabilise the NLC and to cause the removal of the Commissioner and myself”.

Based on an attack on the procedure of Bailey’s appointment, on the way in which his terms of reference were set and on the way he proceeded, Nevhutanda urged that Bailey’s report “be rejected in its entirety”.

It was difficult to establish what happened next.

By April 2017, Kaphuma had resigned and the board members who had supported her – Weapond, Mokoka and Reddy – did not have their terms renewed.

Neither Weapond nor Mokoka would provide information to amaBhungane and Reddy succumbed to cancer in October 2017.

The then minister, Davies, told amaBhungane he had “no real personal recollection of the matters you raised” but would forward the questions to the department.

But it was hard to get answers out of the department.

Director general Lionel October texted a response, stating: “We had lots of issues with the board as they acted in a very legalistic manner and did not want to cooperate with the agency management unit of the department.”

Eventually spokesperson Sidwell Medupe responded, setting out the ministry’s version.

He wrote: “The chair of the Audit Committee sent the report to the Ministry… The legal status of the report was disputed within the Board.

Medupe said the minister had received legal advice from the department to the effect that there was not sufficient evidence to bring any action against the chair and it was the responsibility of the board to deal with any others mentioned in the report.

Medupe echoed October, saying: “The environment is exceptionally litigious and if due process is not followed, it often undermines the outcomes of investigations… Recently, the DTIC has laid criminal charges regarding misuse of funds in the Dhenze project.”

Dhenze is one of the projects in which both Letwaba and Ramulifho are implicated. Ramulifho’s organisations have received at least R60-million in lottery grants for a variety of projects.

So, instead of galvanising investigation and reform, the report has lain dormant – and Nevhutanda last year even persuaded minister Patel to extend his term by a year, which runs out at the end of this month.

Now, five years after Kapumha blew the whistle, it appears Patel has had enough. Nevhutanda is leaving but there is a continuing battle over the secrets he is leaving behind.

Bailey’s report shows why.

Disclosure: The late Govin Reddy was amaBhungane investigator Micah Reddy’s father.

Note: The NLC was previously known as the National Lotteries Board. For the sake of clarity we have not made a distinction between the two in the article.