President Jacob Zuma at the ANC Youth League Conference in 2013. Photo: Greg Nicolson (courtesy of Daily Maverick who have copyright on this photo)

15 February 2016

President Jacob Zuma’s brief comments in the State of the Nation address on instituting a national minimum wage (NMW) in South Africa suggest that government may be looking at this policy the wrong way round.

The NMW is an ANC policy that the President should be championing. The evidence is unequivocal: a national minimum wage, correctly set, will almost certainly reduce poverty and inequality while increasing the wages of the working poor. Inequality, the new international consensus tells us, is bad for growth. An NMW is therefore one part of our economic solution, not a potential problem.

Instead, President Zuma made cautious remarks focusing on the implication that an NMW has the potential to impede employment creation and growth and hurt small businesses. This is a shift from previous government statements (see, for example, here and here) and may suggest a preoccupation with placating business groups and ratings agencies.

His remarks ignore the point and benefits of a NMW, while unduly focusing on risks that have been shown to be overstated.

International studies and local economic modelling – presented at Wits University’s recent NMW symposium – show that by raising wages of the poor an NMW can increase consumption, thereby boosting spending and hence output and growth, and reduce poverty and inequality. A clear consensus exists that, on average, minimum wages, correctly set, have a very small or neutral impact on employment. Here is a “people’s policy” the ANC should be shouting from the rooftops.

At the symposium, Professor Roxana Maurizio, a Latin American expert, highlighted the steep rise in real minimum wages in Argentina, Brazil and Uruguay. These increased by as much as 200% between 2000 and 2012. This, she showed, played the most important role in reducing the gap between the top and bottom end of wage earners (the 90/10 ratio) and between those at the middle and bottom end (the 50/10 ratio). Both ratios fell 18% and 33% in Argentina and Brazil respectively. In Uruguay, the 90/10 ratio fell by 10% and the 50/10 ratio by 9%.

Increasing minimum wages was the main cause of this decline. Evidence from other developing countries presented by Uma Rani, an expert from the International Labour Organization, supported the role of minimum wages in reducing inequality.

For the UK and US, Professor Alan Manning from the London School of Economics, showed that a stagnant national minimum wage in the US played a leading role in increasing wage inequality between middle and bottom earners from 1979 to 2009. In the UK, after the institution of an NMW in 1999, Manning notes that there is ‘strong evidence that higher levels of minimum wages are associated with lower levels of wage inequality’; for some groups the NMW accounted for up to 50% of the decline in inequality (measured by 50/10 ratio).

This should be encouraging to South African policy makers given our world-beating levels of inequality and deep poverty. Half of full-time South Africa workers earn below R3,640 while approximately 5.5 million workers can be considered to be “working poor” with their wages unable to bring them and their dependents above the poverty line. According to Statistics South Africa the gap between very high wage earners (the 95th percentile) and wage earners close to the very bottom (the 5th percentile) grew from around 30 times in 2010 to almost 50 times in 2014.

Two statistical modelling exercises commissioned by the Wits research project confirmed that the NMW is likely to have similar inequality-reducing effects in South Africa as has been observed elsewhere.

Using the United Nations Global Policy Model – a forecasting model used by the G20, a group of the world’s 20 largest economies – shows the positive impact of workers in South Africa receiving a “larger slice of the pie” (i.e. through an increase in the “wage share”). This results in an increase in available income, consumption, output and growth.

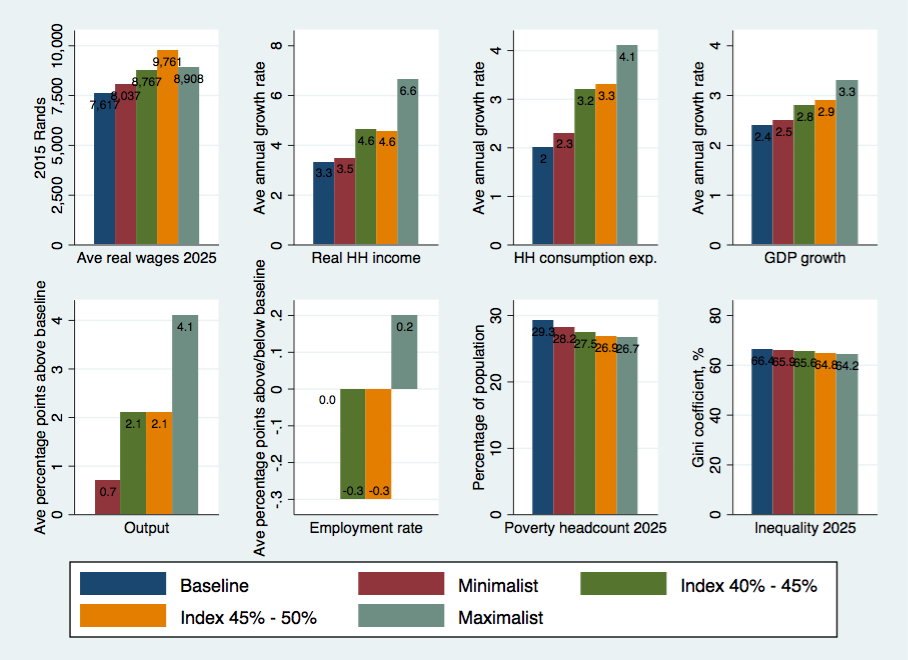

In another modelling exercise, Dr Asghar Adelzadeh uses a detailed and customised econometric model for South Africa, showing the consequences of a direct rise in wages for low-income earners through the institution of a NMW. The four different NMW levels are compared to a scenario in which the economy is left to evolve along its current path – the “business-as-usual” or “baseline” scenario.

The results show that, depending on the level modelled, by 2025 average wages are between 6% and 28% greater than in the baseline. This can result in up to a doubling of the average growth rate of household income, thereby stimulating increased consumption.

In the middle-of-the-range scenarios, output rises by 2.1 percentage points and in the highest scenario GDP growth is 0.9 percentage points above the baseline. Wages amongst the lowest earners rise most, poverty falls dramatically, and inequality declines.

All of this occurs together with a slight fall in the employment rate of up to 0.3 percentage points below the baseline, while the overall number of people employed increases (as the population grows and economy expands).

This very slight nature of any negative impact on employment – which preoccupied President Zuma in his brief remarks – is confirmed by the international experience, also presented at the recent symposium.

Professor Alan Manning showed this to be the case in the developed world, with Professor Roxana Maurizio and Dr Lotta Takala-Greenish focusing on the developing world (see here too).

Ben Stanwix, from UCT’s Development Policy Research Unit (DPRU), presented the existing South African evidence on the impact of sectorally-set minimum wages. The results are varied and differentiated by sector, region, age, gender and a range of other variables, but the overall (local and international) evidence points towards minimal consequences for employment.

This is because, as the presenters noted, firms adjust to higher wage costs in a myriad of ways; wage costs are not the sole factor which determine investment, and increased spending by workers can boost economic growth. Reducing inequality we have been told, including by the conservative International Monetary Fund, is good for growth. An intervention that tackles inequality in South Africa therefore has a number of potential positive spillover effects.

Achieving these positive effects requires the NMW to be carefully constructed and correctly set. It should be set in a way that addresses workers’ basic needs and reduces working poverty and inequality. It should be designed in a manner that maximises benefits and minimises any potential negative consequences.

The ANC and government have chosen to pursue instituting a national minimum wage. It is a bold and progressive policy that could change the lives of millions of poor South Africans for the better. This is the message we should have heard from President Zuma.

Views expressed are not necessarily GroundUp’s.

See also Jeremy Seekings’s article on the level to set an NMW.