17 years defending the right to fight

May Day last week should have been a time for reflection, not celebration; reflection about the potentially dire situation the labour movement now finds itself in. It is a situation brought about by tensions largely resulting from the ongoing global economic crisis that has impacted on every aspect of society. To help with this reflection, Business Report is this week making available copies of my book, Right to Fight, to the first five correct answers drawn from responses to the question below.

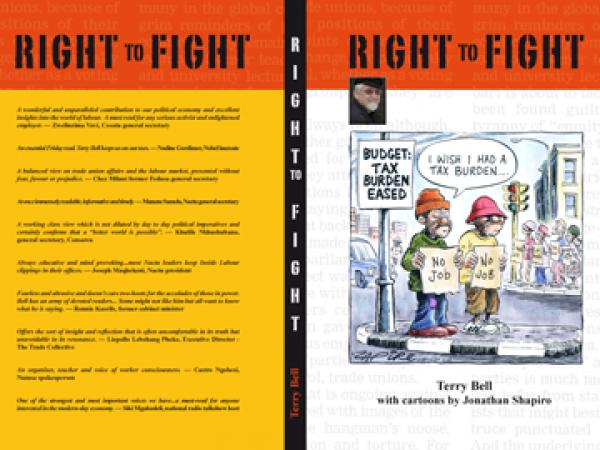

Right to Fight is a selection of the past 17 years that this column has appeared on Fridays in Business Report. At the time the column was launched, the first of 17 collections of the political cartoons by Jonathan — Zapiro — Shapiro also appeared. A selection of 19 of these is also included in this book, and these, in graphic form, sumarise what I think are the major issues we all face and have faced for each of the past 17 years.

These are, I think, years bracketed by two political watersheds: 1996 and 2012/13. The period began with great promise for working people, with the introduction of the Constitution containing a rightly lauded Bill of Rights and the gazetting of the Labour Relations Act (LRA). But it also heralded the emergence of an economic policy clash that persists today. Seventeen years down the line, we saw the bloody tragedy at Marikana, the Boland strikes and the clear rifts that now persist within Cosatu and the governing, ANC-led alliance. These obviously reverberate throughout the labour movement.

Much of the internal tension dates back to the ideological clash that emerged openly in 1996. It centred on economic policy and has its roots in the original social democratic orientation hinted at in the ANC Freedom Charter. This was reinforced by Nelson Mandela when, on his release from prison, he announced that “nationalisation is the policy of the ANC”.

Such talk sent shivers of apprehension throughout the business sector. There were fears that the new, ANC, government would take a less than laissez faire view of the economy; that in order to start righting the wrongs of apartheid a perhaps high tax and redistributive regime might be introduced.

Those who had benefitted often hugely from apartheid were loathe to see such benefits reduced in a non-racist era. And their fears were only slightly assuaged when soon-to-be President Mandela emerged from the World Economic Forum (WEF) gathering in Switzerland in 1993 to reverse his stand on nationalisation. However, it was known that the ANC Macro-Economic Research Group (Merg), sidelined at the WEF, had drawn up a comprehensive policy that placed the concept of redistribution above that of economic growth.

Reacting to this, the business lobby, in February 1996, produced a liberal, free-market policy proposal entitled Growth for All. The combined labour movement had, by then, turned to Merg, debated these proposals, and responded in April of that year with a comprehensive Social Equity & Job Creation publication. It contained a hardly revolutionary set of proposals, but these placed the need to redistribute wealth to the forefront, the direct opposite to the orientation of Growth for All.

But 1996 also saw the government, and in particular, Thabo Mbeki, Trevor Manuel and Alec Erwin also hard at work refining policy proposals drawn up with inputs from bodies such as the World Bank. This emerged in May as the Growth Employment and Redistribution (Gear) programme, a liberal outline based on the now much derided “trickle-down” theory supported by business. The die was cast and it would affect everyone within South Africa.

Cosatu, with 21 members in the new, ANC-dominated parliament, failed to actively promote its Social Equity document and criticism of Gear was initially muted. But the unions, across the federations and among independents, continued to exercise their legal right and moral duty to fight on various fronts. This roller caster ride through almost two decades is the focus of this book that I hope gives a more fully rounded idea of the role of unions, a role that extends well beyond demands for better pay and conditions.

Trade unions and their federations created a major job creation fund, opposed privatisation as well as discrimination on the grounds of gender and sexual orientation. Many of these can be counted as victories; other battles are ongoing, such as the support for the campaign to have value addd tax (VAT) removed from books to try to help make a reality of the government slogan: “Build a nation of readers”.

The columns and cartoons in Right to Fight give a glimpse of this often tumultuous period, illustrating the foibles, failings and successes of Cosatu, Fedusa, Nactu and various independent unions. Hopefully, they also provide an antidote to some of the myths surrounding the recent past and make for worthwhile reading. Cosatu president Zwelinzima Vavi, Nobel laureate Nadine Gordimer and former government minister Ronnie Kasrils are among those who have given it the thumbs up.

The selection of columns and cartoons that comprise this book is also part of the ongoing campaign against VAT on books that has been joined by independent booksellers such as Cape Town’s Book Lounge and Kalk Bay Books as well as Xarra Books on Constitution Hill. The have agreed to absorb the VAT charge and the book sells in such stores at no more than R100. Other booksellers are invited to join.

Belatedly: May Day greetings to all readers and to all workers, employed and unemployed.

Win a copy of Right to Fight

Answer this question: Who was the first general secretary of Cosatu?

Send your answer to business.report [at] inl.co.za putting “competition” in the subject line. Alternatively, post your answer to: Competition, Business Report, P. O. Box 1014, Johannesburg 2001

Right to Fight is also available to South African readers at R100 (p&p paid) by mail order through saredworks [at] gmail.com or through RedWorks, P. O. Box 373, Muizenberg 7950.

Support independent journalism

Donate using Payfast

Don't miss out on the latest news

We respect your privacy, and promise we won't spam you.

Next: Aged Out

Previous: Safer Communities

This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.