1976 in Cape Town: recollections of 11 August

“We did not burn the schools”

While many think of the Soweto student uprising when June 16 comes every year, students also rose up in Cape Town and elsewhere in the months that followed.

“We are going to talk about the events of 11 August not 16 June,” says Kenneth Fassie, one of five former students at Langa High School in 1976 that met with GroundUp.

Kenneth Fassie’s brother, Themba, who bares a striking resemblance to their famous sister, Brenda Fassie, is also present, as is Baba Zondi, Ketani ‘Chisa’ Katanga and Terrence ‘Tapepa’ Makhubalo.

Kenneth Fassie was 17 at the time and in form three (now grade ten). They were writing exams when Soweto exploded.

“When we came back to school after the exams, the staff room was like a police station. Police were there and they provoked us, searching us for petrol bombs. After a month of harassment from police, we held a meeting where we used to sit, in a place we called Betane,” says Fassie.

Betane was an open space not far from the school where students who were excluded from school for not paying school fees would go and sit to avoid going home.

On 10 August, they decided to have a mass meeting on the school soccer field, where it was decided that the following day they would march to the Langa police station in solidarity with the students in Soweto and against Afrikaans as a language in schools.

Katanga was 20 and in form four (grade 12). “When we were leaving the school on the 11th - it was in the morning because we didn’t even attend mass - there were police everywhere with dogs. We were holding placards and they told us we are going to intimidate the younger children.”

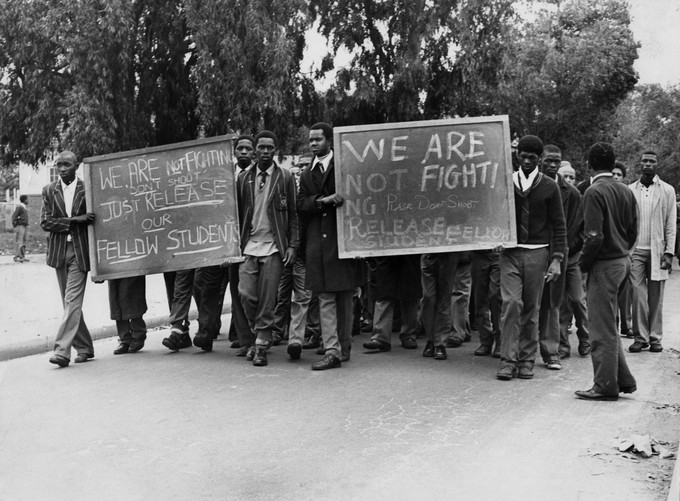

“On first attempt, we got shot at and some people were arrested … We then went back to our meeting place and we decided to go again, and the second time we had placards that said, ‘Release our fellow students - we are not fighting’. We had not even crossed the road to get to the police station and they shot at us,” says Kantanga.

Kantanga vividly remembers every road they took to get to the police station and names them.

The protest was meant to be peaceful with no violence. 17-year-old Xolile Mosie was the first student to be shot and killed in Cape Town. Students threw stones in retaliation, while the police shot live ammunition and left many students injured.

“We were young and active and Xolile was hyper. He was dancing around and was right there … The police who were in front are the ones who shot him. It was someone who was either behind them or behind the trees at the police station. We still do not know who shot him,” says Katanga.

Mosie died immediately. Then, says Katanga, “All hell broke loose.” His body lay on the side of the road for an hour before it was picked up by the police and unceremoniously thrown into a bakkie.

Makhubalo was the organiser of the meetings they held – every day at the time. He was detained more than once. He refuses to talk about some of the things he experienced.

He says when people were arrested they were tortured and the police tried to co-opt people to spy.

“This caused a lack of trust among each other because there were now snitches and many people decided to skip the country. You did not know who to talk to or who not to talk to,” he says.

“We had to move places [to meet] … Students from Gugulethu, who attended school in Langa, told students in their community and vice versa. Then we had communities like Bonteheuwel and other communities join in.”

Meetings moved from Fezeka High School in Gugulethu to ID Mkhize High School to confuse the police.

Community joins the protest

After the death of Mosie, the community joined the protests. Shops were looted and burnt and so were schools. Youth that were not students made the township ungovernable.

Katanga says police went door to door searching for people.

“They would come at 5 am searching for students from Langa High School … They would threaten our parents, saying if we do not go to the police station they will kill us, and some of the parents had no choice but to say yes when they were asked.”

Kenneth Fassie went into exile and only returned in 1992, spending 15 years of his life away from his family.

“No one wanted to go and leave their families behind, but we had no choice. We had to go for our safety,” he says.

Violence became a constant part of life. Just the sight of the police would start stone throwing.

“People started talking about the release of the prisoners on Robben Island. As students we had no political affiliation at the time, but because the underground movements were political they used that as an opportunity to recruit people. And as more adults joined, the protests became more political … It became more about black consciousness,” says Fassie.

Schools closed

Katanga says that even though most of the students did not go back to school, many have made something of themselves. But they also lost friends, neighbours and family members in the violence.

“For the rest of 1976, there was no school. In January, people were given the choice to go and write exams and go back to class, but some people chose not to; some could not because they had gone to exile.”

Later in 1976, a group known at that time as “Amabhaca” from Nyanga East were used as a shield by police. Langa residents walked street by street recruiting men to fight the Amabhaca.

“If people knew there is a man staying in the house, they would go and knock and ask for that man to join and the crowd, and that was done in every street,” says Katanga.

Police heard of the plans. Many people were shot and injured and some lost their lives.

Baba Zondi, who was 18 at the time, says the protests went quiet and then started up again in 1980. He left school mid-year.

Asked what they thought of the current situation in schools and universities, Zondi says, “We are not against them. We also wanted free education, but at the same time we wish they would stop destroying the resources they already have. We are against the burning of schools. We did not burn the schools as students. It was when the broader community joined that schools were burnt. We had no plans of doing that.”

Support independent journalism

Donate using Payfast

Don't miss out on the latest news

We respect your privacy, and promise we won't spam you.

© 2016 GroundUp.

This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

You may republish this article, so long as you credit the authors and GroundUp, and do not change the text. Please include a link back to the original article.