Appeal Court rules that City of Cape Town acted unlawfully

Ruling clarifies what constitutes lawful “counter-spoliation” when it comes to land occupation

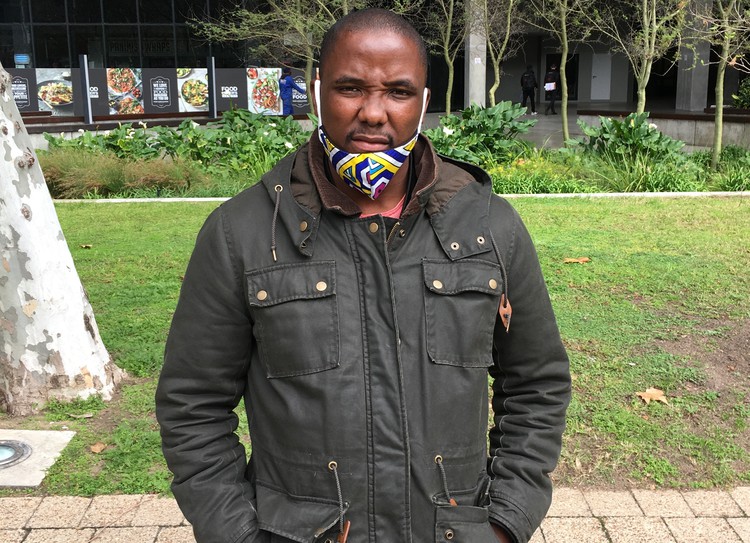

Bulelani Qolani was dragged naked from his shack on 1 July 2020 by City of Cape Town law enforcement officers. Photo: James Stent

- Bulelani Qolani was dragged naked from his shack eviction in July 2020 during an eviction of land occupiers in Cape Town.

- The City of Cape Town argued that the eviction was lawful under the remedy of “counter-spoliation”.

- Counter-spoliation, in this case, refers to taking back property that had been unlawfully occupied, without going to court first.

- The Supreme Court of Appeal has ruled that the City could not justify its actions in this eviction using counter-spoliation.

- The counter-spoliation remedy can only be used before a person has put up any poles, lines, corrugated iron sheets or similar structures with or without furniture, which point to effective physical control of the property occupied, the court explained.

The Supreme Court of Appeal has confirmed that the City of Cape Town was wrong in applying the remedy of “counter-spoliation” when it demolished the shacks of land occupiers in and around the city in 2020.

The City had argued that it could use the remedy at any stage before a fully constructed informal structure becomes occupied as a home, but the appeal court has said this is not permissible. The court said this amounted to the City taking the law into its own hands. Such evictions can only take place within a “narrow window” without having to go to court, the judges said.

The City took the matter on appeal following an equally damning ruling in July 2022 by three Judges in the Western Cape High Court in an application brought by the South African Human Rights Commission (SAHRC), the EFF and others, with Abahlali BaseMjondolo as an amicus curiae.

The application was sparked by the widely-publicised eviction of Bulelani Qolani, who was dragged naked from his shack during the evictions, which were carried out by the city’s Anti-Land Invasion Unit (ALIU).

In this week’s ruling, SCA Judge Connie Mocumie, writing for the unanimous court, said the removals, which took place between April and July 2020 without a court order, resulted in shacks being dismantled, belongings destroyed, people being injured and others being treated in the most undignified and humiliating manner, such as Qolani.

She said as a general rule, a possessor (such as the City) who has been unlawfully dispossessed (through land occupation) cannot take the law into their own hands to recover possession.

But, she said, if the recovery (of the land) is done immediately - or at once - then it is regarded as a mere continuation of the existing breach of the peace and is consequently condoned by law. This is known as counter-spoliation.

This is only permitted where peaceful and undisturbed possession of the property has not yet been acquired.

The City, in arguing that the remedy of counter-spoliation was lawful, had to show that the homeless person was not in effective control of the property, the judge said.

“This means, if a homeless person enters the unoccupied land of the municipality with the intention of occupy it, the municipality may counter-spoliate before the person has put up any poles, lines, corrugated iron sheets or similar structures, with or without furniture, which point to effective physical control of the property occupied.

“If the municipality does not act immediately, it will have to seek relief from the court through an ordinary interdict or under the Prevention of Illegal Eviction from and Unlawful Occupation of Land Act (PIE).”

Judge Mocumie said the City had argued that counter-spoliation was constitutional. If the City had been forced to get an interdict, or an order under PIE, by the time the court granted such orders, the occupiers would have settled on the land, the City said.

Under PIE, the City would be bound to provide alternative accommodation to the unlawful occupiers, and consult and negotiate and establish whether children and women were affected. The City argued that this is onerous and expensive and it had a long list of people waiting for housing for the next 70 years.

The matter was best left to the discretion of the City officials who carried out evictions in as humane as possible manner, under trying and sometimes violent circumstances, it argued.

The SAHRC, and others, argued that there was no guarantee that officials would not abuse their powers and the better option was to have the supervision of the courts.

The approach the City wanted to adopt - that of “trust us” - could not be correct and the City could not be left to be the judge and executioner in its own case.

Judge Mocumie said it was evident from an affidavit by the City’s own official that structures had already been erected when the ALIU arrived.

“This meant that the possessory element was already completed. The structures had assumed permanence and the invaders were therefore in peaceful possession.”

She said demolitions occurred after officials made a subjective, visual decision that the shacks were unoccupied. This without reference to any objective guidelines, or guidance from superiors who might be more sensitive to the socio-economic circumstances of marginalised people.

The appropriateness of the time within which to counter-spoliate was left wholly within the discretion of the City’s employees and agents “and this is often capricious and arbitrary and cannot be legally countenanced”.

She said while the City was facing an overwhelming demand for housing, this did not justify what it had done.

A municipality might be able to successfully counter-spoliate - as it was still part of our law - but it must do so immediately, within a narrow window period.

To change the law would have huge ramifications and might even require an attack on the constitutionality of PIE, she said.

“In the meantime, courts should deal with these matters on a case-by-case basis until those issues are properly raised and dealt with fully, fairly and pertinently,” Judge Mocumie said, dismissing the appeal and ordering the City to pay the costs.

In an earlier related appeal, the SCA overturned a ruling that the City must pay R2,000 to each person affected by the evictions. The court said this had been granted as part of an interim interdict, which was not permissible.

There was also insufficient detail at the time as to what items were destroyed or removed and from whom.

Support independent journalism

Donate using Payfast

Don't miss out on the latest news

We respect your privacy, and promise we won't spam you.

Next: Buffalo City ratepayers march to City Hall, rejecting electricity fee

Previous: Census 2022 results are “incoherent and implausible”

Letters

Dear Editor

"She said as a general rule, a possessor (such as the City) who has been unlawfully dispossessed (through land occupation) cannot take the law into their own hands to recover possession."

This judgement is proof that illegal activity will proliferate in SA. So the people can occupy unlawfully? But the City cannot remove them?

© 2024 GroundUp. This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

You may republish this article, so long as you credit the authors and GroundUp, and do not change the text. Please include a link back to the original article.

We put an invisible pixel in the article so that we can count traffic to republishers. All analytics tools are solely on our servers. We do not give our logs to any third party. Logs are deleted after two weeks. We do not use any IP address identifying information except to count regional traffic. We are solely interested in counting hits, not tracking users. If you republish, please do not delete the invisible pixel.