Auditor accused 3Sixty managers of “constructing evidence”

3Sixty Life: a lesson in how not to run a company, part two

3Sixty Life, the NUMSA-owned insurer, has been facing insolvency.

With new acting CEO Khandani Msibi at the helm in 2021 it might have seemed that the problems plaguing 3Sixty Life, the insurer owned by the National Union of Metalworkers (NUMSA), would be solved. But the company’s external auditors quickly sounded new alarm bells.

For months, the financial authorities had warned that the company was sliding towards collapse. Then in November 2021, Pravesh Hiralall, a director at SizweNtsalubaGobodo Grant Thornton, the company’s auditors, announced that he had not been able to finalise the audit for the 2020 year.

In a 22 February 2022 affidavit, Hiralall said that he and his team had “experienced challenges” in their interactions with management at 3Sixty Life which made it impossible to conclude the audit of the financial year ending in December 2020, which had been due in October 2021. Hiralall said he had not been provided with information and documents essential to the audit.

He also reported extraordinary behaviour from the CFO of the 3Sixty Group, Olu Luthanga, and the CFO of 3Sixty Life, Ellan Cornish. He claimed they proposed to him how he should make up financial statement line items. Hiralall said that his team was “impeded” by 3Sixty Life’s management “seemingly constructing evidence to address audit queries”.

Meanwhile the issue of the money siphoned off from 3Sixty Life’s With-Profit fund would not go away. Battling a lack of funds in January 2021, 3Sixty Life had withdrawn R70-million from the With-Profit fund — which is built up by policyholders who pay extra to ensure a larger payout when they claim — to pay out pending claims. The board presented this as a loan, to be repaid by the end of the year.

And according to a 31 December 2021 report from its internal auditors 3Sixty Life had “repaid” R14 million of the loan. This “repayment” was framed by 3Sixty Life as an in-kind repayment, namely that by not charging the With-Profit fund in administration fees, they had repaid R14-million.

The Prudential Authority disagreed, pointing out that there had been no payment back into the fund.

3Sixty Life’s next plan to get out of the financial hole was to sell a company belonging to another part of the 3Sixty Group. This was to be done by the end of May 2021. But on 31 May the new CEO Msibi wrote to the Prudential Authority to say that due to “unforeseen delays”, the transaction could not be completed by end of May. Msibi asked to be allowed until the end of June to sell the company and use the funds as a capital injection into 3Sixty Life. Meanwhile, he said, 3Sixty Life’s solvency position had shown “remarkable improvement” and that he expected May’s financials to show “spectacular improvement”.

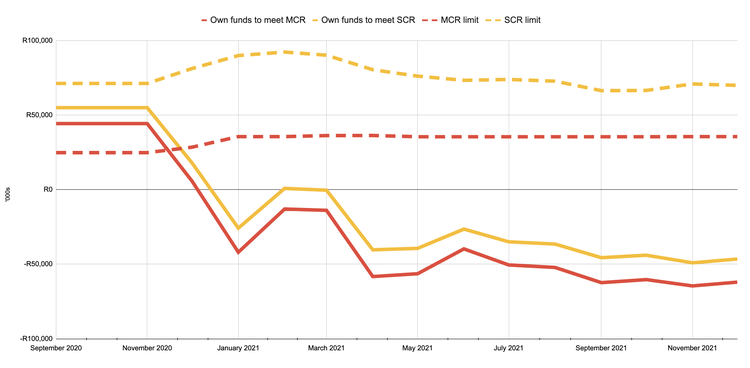

Dotted lines are the minimum and solvency capital requirement limits. Whole lines are the capital that 3Sixty Life had available to it to meet these limits. Where the line falls below R0, 3Sixty Life’s liabilities exceed their assets. Data between September 2020 to October 2021 are from 3Sixty Life management accounts provided to the Prudential Authority; data for November and December 2021 are from projections by 3Sixty Life’s actuary.

At the end of June 2021, 3Sixty Life required R75-million to meet their minimum capital requirements, an improvement from end-May, when they required over R90-million.

In an 11 June reply, the Prudential Authority accepted the extension but warned that if the company had not recapitalised by the new deadline, the regulator might need to step in.

On 17 June, Msibi wrote to the Prudential Authority again to say the 3Sixty Group “had sold one of its key assets, SALT Employee Benefits (SALT EB)”. SALT EB is a retirement fund administrator that had been bought by the 3Sixty Group, with the aid of a loan from 3Sixty Life. Except not quite. Apparently the buyer - SALT EB’s former owner - had not yet secured funding from ABSA to conclude the sale and so Msibi was “not able to give clear indications of the transaction conclusion”.

The end-of-June deadline extension was missed.

On 2 July, Msibi wrote to the Prudential Authority to ask for another extension of the deadline to meet its minimum capital requirement — the minimum a financial services company must hold if it is not to default — to 31 August. He also suggested the Prudential Authority “should consider relaxing current regulations”. At this stage, six months had passed since 3Sixty Life breached its minimum capital requirement.

On 16 July, the Prudential Authority replied that it would accept the extension to recapitalise 3Sixty Life to 31 August, on the understanding that the sale of SALT EB was completed by 16 August.

The sale did not happen on 16 August.

Instead, on 13 August, Pauline Karuiki of the Dignity Group wrote to the Prudential Authority to complain that 3Sixty Life had not paid claims that it had underwritten to the tune of R1.7 million, lodged between 3 and 11 August that year, and had not received any response from 3Sixty Life. “We have claimants and their families in our offices crying, wanting the money to bury their loved ones over the weekend,” wrote Karuiki.

By the end of September, 3Sixty Life required R98-million to meet their minimum capital requirements.

On 4 October, Kuben Naidoo, CEO of the Prudential Authority and Deputy Governor of the Reserve Bank, wrote to Msibi. He said that in the absence of the recapitalisation plan, the Prudential Authority was considering regulatory action, including restricting the company from taking on new business.

Msibi responded the same day to plead that 3Sixty Life should be allowed to get new business from “internal channels”. Then on 18 October, Msibi wrote to the Prudential Authority to say the SALT EB plan was off the table and promised that 3Sixty Life would have a “Plan B” by 5 November.

The SALT EB sale would have been for R70-million. At end-October 2021, 3Sixty Life’s own funds available to meet their minimum capital requirements was minus R60-million, according to their own management accounts, and they required over R95-million to meet their minimum capital requirements.

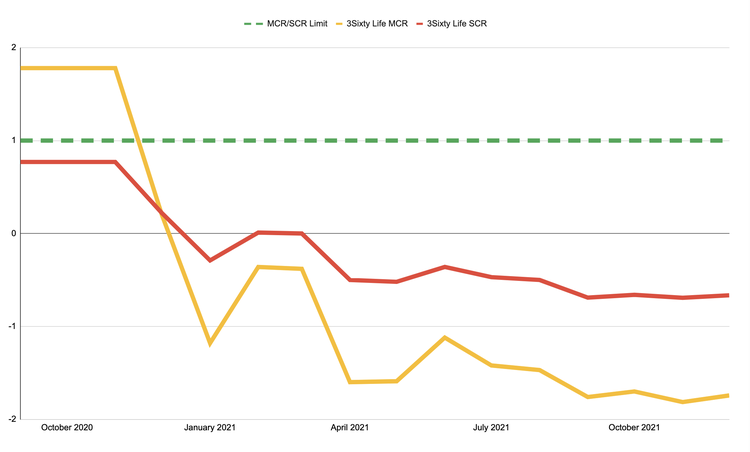

3Sixty Life’s minimum and solvency capital requirement ratios over late-2020 and 2021. Ratios of both the MCR and SCR must be equal to one. Ratios below 0 indicate liabilities exceed assets and the company is insolvent. Sources as above.

On 20 October the Prudential Authority asked to meet the board of 3Sixty Life to understand what this Plan B would entail, and how it would solve the company’s problems.

On 9 November 2021, 3Sixty Life was informed by the Prudential Authority that it was now prohibited from taking on new business, and that if it failed to recapitalise to at least meet its minimum capital requirement by 1 December 2021 the Prudential Authority would “use available legal remedies to protect the interests of policyholders”. These measures could include curatorship (under section 54 of the Insurance Act) or winding up the business of the company (under section 58 of the Act).

In a meeting between 3Sixty Life and the Prudential Authority on 26 November, the regulator was told that the SALT EB sale was again back on the table, with a signed agreement due by the end of November.

The Prudential Authority was told that in addition, 3Sixty Health, another company in the 3Sixty Group, had applied for an overdraft facility of R40-million from ABSA, R20-million of which would be loaned to Doves, which would invest it as equity in 3Sixty Life. But, according to the Prudential Authority’s papers, ABSA was reluctant - without audited financial statements, and with the company insolvent, such a loan would be a risk.

On 30 November, the SALT EB sale had fallen through again.

On 7 December, Msibi wrote to the Prudential Authority. He said that 3Sixty Life had not met its minimum capital requirement by 1 December. He pleaded with the regulator not to intervene and offered, at last, the sketch of a new Plan B.

The 3Sixty Group, he said, had decided to cede R130 million worth of property owned by the Doves Group (3Sixty Life’s immediate parent company). A total of 62 “unencumbered” properties, worth R122-million had been identified. The transfer was to raise 3Sixty Life’s minimum capital requirement ratio from -1.85 to a safe 1.44 ratio.

But the Prudential Authority was not convinced. There were serious doubts about the terms of the transfer, and particularly whether the properties, which were occupied by Doves funeral parlours, were in fact “unencumbered”, as claimed.

Over a year had now passed since 3Sixty Life had breached its solvency capital requirement, and close to a year had passed since its minimum capital requirement was breached. The company had been insolvent for the entire year.

The Prudential Authority decided to take action. On 15 December it approached the High Court in Johannesburg to apply for an order to place 3Sixty Life under curatorship, which was granted on 21 December.

We intend to report what happened after that in a future article.

Information in article was drawn from publicly available court papers submitted in the curatorship matter. From what we can tell, Luthanga and Cornish did not respond to Hiralall’s allegations about their behaviour in that record. We emailed both Luthanga and Cornish to offer them a response to Hiralall’s allegations. Luthanga’s 3Sixty Group email address, which was working in 2021, bounced our email back, and we have not received a reply from Cornish. We will include any response if or when it arrives.

Explainer: The two financial regulators

The Prudential Authority regulates banks and insurers and some markets. Its role is to help preserve financial stability across the South African market, making sure that people who are supposed to be covered by a financial provider are, in fact, covered. If a financial provider takes on a significant loan, or change in ownership, or gets into money trouble, the Prudential Authority must know.

The Financial Services Conduct Authority, on the other hand, is primarily concerned with whether customers of banks and insurers and other financial services companies are being treated fairly and in accord with regulatory guidelines. If a company adds a fee that is not permitted by statute, or increases fees without warning, it would investigate and take action, for instance by levying fines.

The Prudential Authority will mostly check that a business is a going concern, while the Financial Services Conduct Authority will monitor the conduct of the business at the level of the customer or client.

Support independent journalism

Donate using Payfast

Don't miss out on the latest news

We respect your privacy, and promise we won't spam you.

Next: No more space for large-scale housing projects, says Western Cape government

Previous: Driftsands community protests over week-long power outage

Letters

Dear Editor

In the midst of all this capital scarcity, Doves seems to have found the funds to buy or lease the very large property formerly hosting the SAB World of Beer. This is a property several times the size of any other funeral parlour that I have seen, and the layout is not suitable for a head office. So I can't see why this occurred.

© 2022 GroundUp. This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

You may republish this article, so long as you credit the authors and GroundUp, and do not change the text. Please include a link back to the original article.

We put an invisible pixel in the article so that we can count traffic to republishers. All analytics tools are solely on our servers. We do not give our logs to any third party. Logs are deleted after two weeks. We do not use any IP address identifying information except to count regional traffic. We are solely interested in counting hits, not tracking users. If you republish, please do not delete the invisible pixel.