Children are dying in pain because they cannot get the medicines they need

Government has not implemented its palliative care plan

I had a patient last year, a four-year-old boy, with a type of cancer called neuroblastoma. After initial treatment, the cancer came back, growing in the confined space between his spine and stomach, causing unbearable pain. His mother was a police officer; a strong, stoical woman who had seen a lot, but she was struggling.

After several weeks, using every available drug, including numbing him from the waist down, I managed to get the pain under control, and he died a peaceful death.

A month ago, a colleague in Durban asked for advice on managing a similar case. She didn’t have access to half the drugs I had (at Red Cross Hospital in Cape Town) and the nurses were refusing to administer even those that were available because they hadn’t been trained how to use them. The child died in excruciating pain.

The difference between my patient’s relatively good death and the nightmare one of the Durban child is access to proper pain relief within an effective paediatric palliative care system.

There are only a few places in South Africa offering proper pain relief, despite the fact that at least a million children are dying from – or living with – incurable conditions. Frustratingly, efforts to remedy this unacceptable situation have ground to a halt.

In 2010, the Hospice Palliative Care Association of South Africa (HPCA) initiated an alliance that hospices, professionals working in palliative care, academics and some officials from the Department of Health. A draft policy was created but never implemented.

Plan never implemented

A turning point came in 2014 when South Africa co-sponsored a resolution at the World Health Assembly in Geneva which called on all member countries to integrate palliative care into the hospitals and community care structures. A section of the resolution highlighted the need for policy-making that was tailored towards the needs of children.

We heard nothing from government until July 2016 when the Health Minister, Aaron Motsaoledi, appointed a 12-member steering committee to develop a palliative care policy. I was invited to represent paediatric palliative care. The policy was approved by the National Health Council in 2017 and by 2018, we had developed an implementation plan. It was quite an ambitious plan, which included:

- Specialist palliative health care teams and beds in all major hospitals and district hospitals.

- The Essential Drug List to include up-to-date palliative care drugs and to make them available to all patients who needed them.

- Palliative care training for all health-care officials, including doctors, nurses, pharmacists, social workers and clergy.

However, it seems that the plan is not being implemented because of financial constraints. A budget was created but not approved or allocated.

We showed that palliative care is cost-effective. The problem with medicine is that we are so cure-focused that we are stumped if we can’t cure a patient. Palliative care comes in at that point – even if we can’t cure, we can manage pain and distressing symptoms. With the proper support, patients can be cared for at home and in the community. With proper counselling, the family of a patient with an incurable condition can accept it early on, avoiding unnecessary, futile interventions. We have patients all across the country being admitted to intensive care units when we should call it quits beforehand and support the family through that end phase.

In an attempt to regain momentum, we have called a public meeting in Johannesburg on 18 March which will include all stakeholders in paediatric palliative care from both government and the NGO sector.

We hope to emerge with achievable goals. If the national policy is not affordable, what can practically be done in the short term?

Practical steps government can take now

We could look at how to make drugs more available. We could train people already on the ground to use those drugs. We could train social workers to better support families.

We should also extend the Care Dependency Grant. This is a grant to families with very sick children: it funds travel to doctor appointments and to fetch medication, as well anything else the child might need such as more nappies or formula.

Currently, the grant is terminated in the month of the child’s death. Yet we see so many cases where a single mother has had to give up her job to care for the child and has been relying on the grant and suddenly she is left destitute. Would it not be possible to extend the grant by three months so that she can get back on her feet and feed her family again?

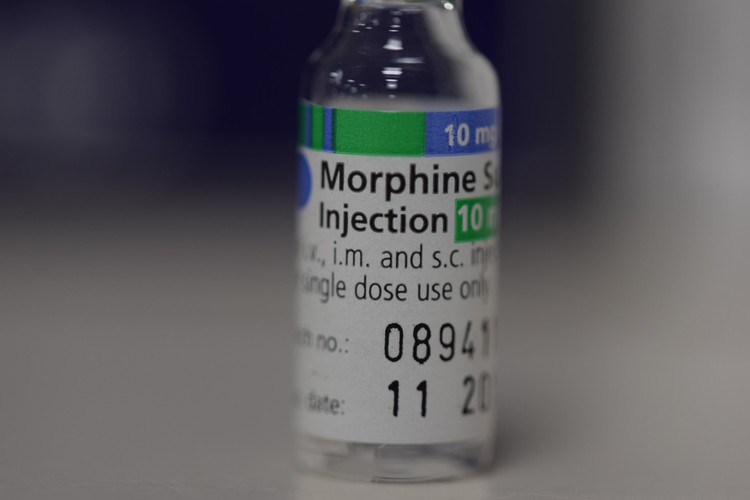

Another problem is access to up-to-date pain relief. Many pain drugs we use for children are off licence, which means that insufficient studies have been done to see if they are safe in children. This poses an ethical dilemma as you don’t often get consent to do studies on these very vulnerable children. So a lot of prescriptions are based on “expert opinion”.

While South Africa’s Essentials Medicine Committee has agreed to include some drugs for the management of symptoms other than pain in the Essential Drugs List where the only available evidence is expert opinion, this still leaves us without certain medications that are being used internationally by paediatricians to manage difficult pain in children.

If that rule were lifted, ordeals such as that suffered by the little Durban girl would be averted overnight.

Views expressed are not necessarily those of GroundUp.

Support independent journalism

Donate using Payfast

Don't miss out on the latest news

We respect your privacy, and promise we won't spam you.

Letters

Dear Editor

No human should be subjected to unnecessary high levels of pain and suffering when there is medication available that would spare them from this, and spare the trauma inflicted on parents who have to witness death under these circumstances.

The medical profession has a responsibility but requires support to enable appropriate training to safely administer the treatment.

Show compassion and mercy please, I beg you.

Dear Editor

My father broke his hip and was forced to lie in his own urine due to nursing staff being more concerned with consuming their food instead of providing him with a urine bottle. They refused to give him any sort of pain medication and left him in excruciating pain for 10 days, waiting for an epidural kit which they said they didn't have to do the operation.

It's not just the kids that suffer in the public hospitals, it's all the patients. Public facilities have turned into butcher shops of misery and suffering. The Cuban doctors employed there, besides having communication problems, are incapable of dealing with the majority of emergencies let alone managing them.

Thankfully my father passed away on the 10th day from a heart attack due to a blood clot from the fracture. He didn't complain, but I for one can't even begin to imagine the pain he must have endured and the disgusting treatment he suffered at the hands of the doctor and pathetic nursing staff more intent in eating KFC than tending to patients.

To top it they allowed a prisoner under SAPS guard to smoke continuously next to him which caused him immense mental stress. I bear an inordinate amount of hatred toward the public sector health profession due to this and similar other experiences as well as this thieving government that are more intent on their own self aggrandisement than providing simple things like pain killers and an epidural kit to patients in need.

I can sympathise with doctors frustrations in not being able to source the required drugs to provide palliative care. It'll only be through initiatives such as individuals menationed in this article that will turn the tide and prevent recurrences of deplorable incidents such as happened to the child above. Doctors that endevour to change the status quo in favour of their patients, albeit dying peacefully and pain free have my eternal admiration and gratitude.

You are truly agents of mercy in those final hours of life.

© 2019 GroundUp.

This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

You may republish this article, so long as you credit the authors and GroundUp, and do not change the text. Please include a link back to the original article.