Explainer: affordable housing in Cape Town

The City of Cape Town has promised 12,000 affordable homes

Maitland Mews, a social housing development built on land previously owned by the City of Cape Town, was completed in March 2023. Photo: Ashraf Hendricks

The City of Cape Town announced earlier this year that it has 12,000 affordable housing units in the pipeline. Here we explain what the City means by “affordable housing”, where these homes will be built and when.

The need for affordable housing in Cape Town is enormous. There are more than 400,000 people on its housing waiting list and half of households in Cape Town earn less than R20,700 a month.

For more than a decade, housing activists from Ndifuna Ukwazi and Reclaim the City have called on the City of Cape Town and the Western Cape Government to build affordable housing in the inner city to counter apartheid spatial planning and put a stop to rapid gentrification. They have obtained court judgments compelling the government to prioritise affordable housing when selling off state-owned land.

In 2022, Mayor Geordin Hill-Lewis announced an “accelerated land release programme”, through which City-owned land would be developed into affordable housing. In the last two years, eleven City-owned land parcels have been released for affordable housing. But construction has not yet started on any of these sites.

What is affordable housing?

The City Council has approved a definition of “affordable housing” to mean homes that cater for households earning less than R32,000 a month.

The 12,000 affordable housing units in the City’s pipeline fall into at least one of the following categories:

- Social Housing: In this model the City sells land to developers, who receive a once-off subsidy from the Social Housing Regulatory Authority (SHRA), a nationally-funded government agency, to build apartments. The developers then rent the homes to households, mainly families, that earn less than R22,000 a month, to recoup development costs and cover maintenance and security. By law, rentals can’t be more than R7,326 a month.

- Open-market “affordable housing”: The City sells land to private developers to build homes for households earning less than R32,000 a month. The details of how this will be structured and regulated are still being worked out.

- Gap Housing: These are state-subsidised houses funded through the national and provincial governments. Once built, the houses are made available for purchase to households earning less than R22,000.

Other state-funded housing models, such as Breaking New Ground (BNG), formerly called RDP, are not included in the City’s “affordable housing”. These other models provide free – as opposed to affordable – housing, and do not prioritise housing near urban centres in the way affordable, Gap and social housing do.

There are also rental units owned by the City itself. But these are not included in the “affordable housing” definition, and the City is busy selling off these units to tenants.

Fewer than 5,000 units have been built

The only “affordable housing” that has already been built is social housing. No Gap or open-market affordable units (as defined by the City) have yet been built.

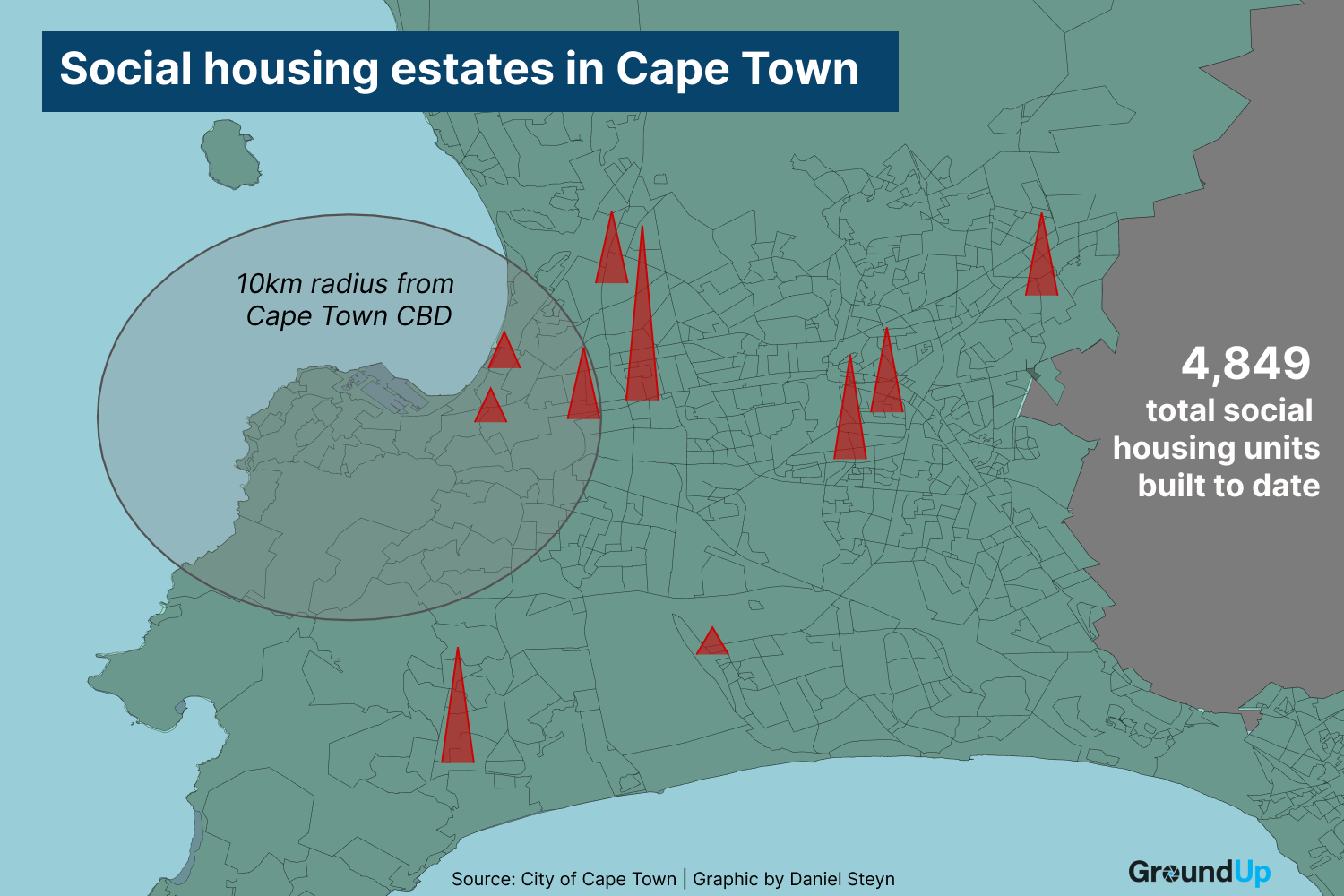

Cape Town has 4,849 social housing units, of which only 855 are within a ten-kilometre radius of the city centre. Some of these existing social housing developments have faced challenges, including rental boycotts.

There are ten social housing developments that currently exist across the City of Cape Town. Three are within a 10km radius of the Cape Town CBD. See an interactive version of this map here.

The City’s 12,000-home pipeline

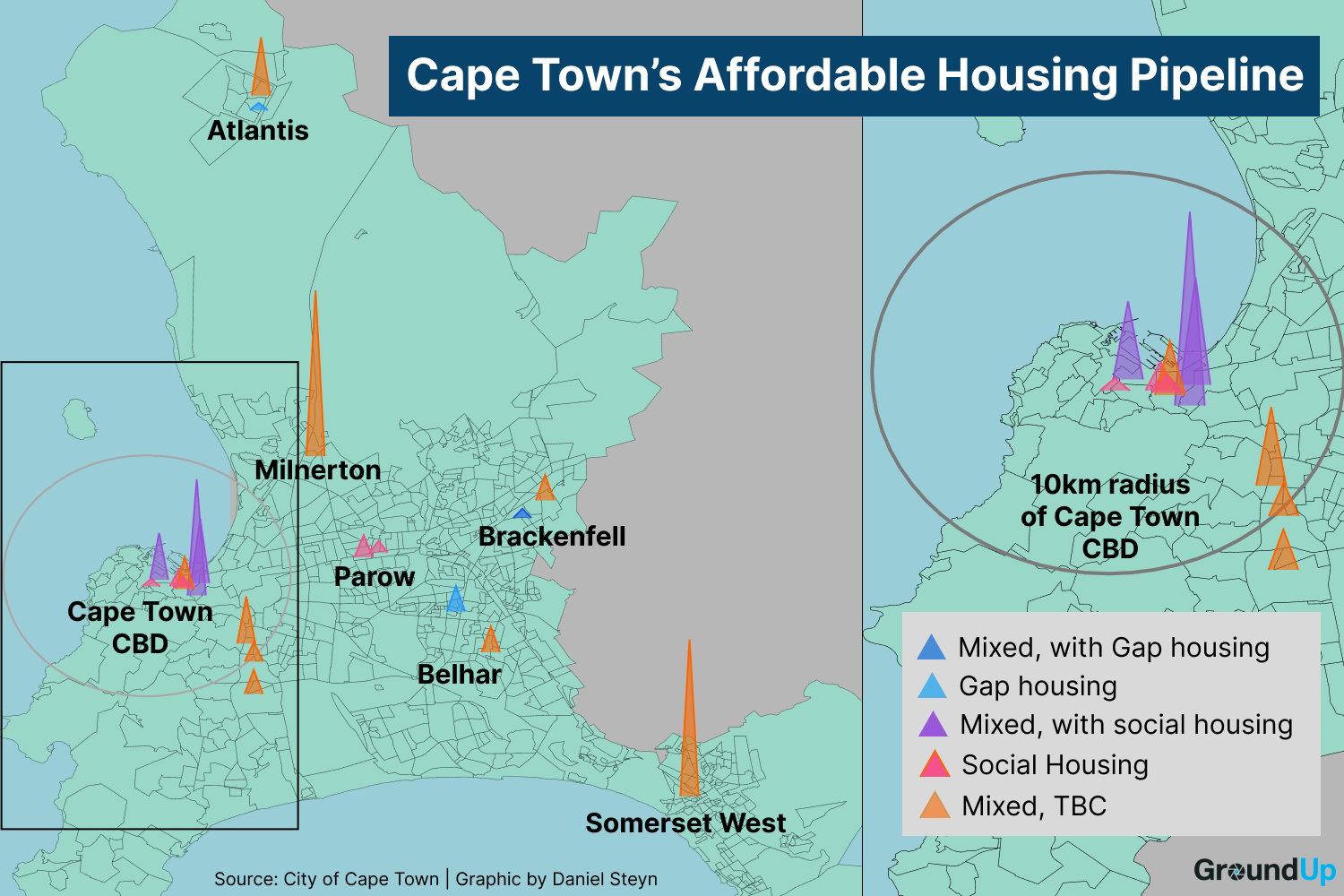

We asked the City for a breakdown of the 12,000 homes in the pipeline. The City provided us with a list of 21 land parcels owned or previously owned by the City, on which an estimated 14,020 housing units will be built.

But not all these units will meet the City’s definition for affordable housing. Some will be high-end, open-market units. The number of affordable units and open-market units still has to be determined for most of the sites.

What we know so far:

- At least 2,741 units will be “social housing” units, subsidised and regulated by the Social Housing Regulatory Authority.

- At least 916 units will be Gap housing.

- At least 683 units will be open-market affordable housing, as defined by the City of Cape Town.

- The remaining 9,680 units will be a yet-to-be-determined combination of affordable housing (social, Gap, or open-market) and high-end open-market units. At least 7,660 of these units will need to be affordable for the City to reach its goal of 12,000 affordable units.

The City is planning at least 12,000 affordable housing units. See an interactive version of this map here.

Location, location, location

Of the 21 developments in the pipeline, ten will fall within a ten-kilometre radius of the Cape Town city centre. Most of the remaining planned developments are in the metro’s other economic hubs.

Ndifuna Ukwazi has criticised the City for prioritising affordable housing developments on the “periphery” of the city, far away from jobs and opportunities.

But Cape Town Mayor Geordin Hill-Lewis has disputed this. He argues that all the planned developments are near “important economic nodes” where affordable housing is necessary. These include Bellville, Century City, Montague Gardens, Paarden Eiland and the “south-east corridor linking Khayelitsha and Mitchells Plain with Claremont and Wynberg”.

Two developments are planned for Atlantis, which is 55km from the city centre. One will include 900 units (the housing model is yet to be determined) and another will have 116 Gap units.

Asked why the City has chosen this location for affordable housing, human settlements MEC Carl Pophaim said that the Atlantis Special Economic Zone means there are “industrial opportunities” in the area and that the demand is suitable for Gap housing.

“One simply cannot ignore potential in communities based on their location away from larger urban centres, such as Bellville or Goodwood or the Cape Town central CBD,” said Pophaim.

Why it is taking so long

Construction has not yet started at any of the sites. The 21 developments are at different stages:

- At seven sites, a developer has been appointed, and planning is underway.

- At 11 sites, the City is still in the process of releasing the land.

- At one site, the old Woodstock Hospital, the first public participation process has recently ended.

- At a site in Earl Street, the City has taken on review a heritage tribunal decision recommending against development at the site.

The seven sites where a developer has been appointed will be a mix of social housing and open-market units. Progress has been slow.

At the Salt River Market site, for example, the land was released in 2022, but the City has to relocate families living on the site before it can be transferred to the developer, Communicare. Also, funding from the SHRA has not yet been approved.

At two other sites – Pine Road and Dillon Lane in Woodstock – the land was released in 2019, but development has not yet started. SOHCO, the developer for these sites, says it is in a “finance application and detailed planning stage” and “changes to the parameters of the social housing capital subsidy programme, combined with difficult site geotechnical conditions, have caused delays.”

The largest planned social housing development, expected to yield 840 social housing units in Pickwick Street in Salt River, was awarded to developer Instratin in 2023. Recent media reports suggest that social housing projects by Instratin are not being maintained or secured correctly. And several projects are unfinished years after they were meant to be completed.

The reports led SHRA to issue a statement saying it will “discontinue support for three social housing projects” implemented by Instratin. This does not bode well for the Pickwick Street development’s funding prospects.

“Considering that this is new information that is being presented to the City, we will look into the matter to evaluate implications on the project going forward,” a City spokesperson told GroundUp.

GroundUp reached out to Instratin for comment via their website contact form but received no response. An email address provided by an agent on their WhatsApp line does not work, neither does the phone number on their website.

Funding constraints in general at the SHRA may continue to delay projects. In 2023, its budget for funding social housing developments was cut by R315-million over three years. The SHRA says its focus has “shifted to working with partners to unlock stalled projects, support funding restructures, and enable the eventual completion of outstanding units.”

Click here for a spreadsheet with details of the planned projects in the City’s pipeline. The City has indicated this data is “dynamic” and subject to change.

This is the first in a series of two articles on affordable housing in Cape Town. On Wednesday, we unpack the City’s plans to develop affordable housing without state subsidies.

Support independent journalism

Donate using Payfast

Don't miss out on the latest news

We respect your privacy, and promise we won't spam you.

Next: R370 grant beneficiaries in Tsakane haven’t been paid in months

Previous: Fidelity fire service is unlawful, says City of Cape Town

© 2025 GroundUp. This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

You may republish this article, so long as you credit the authors and GroundUp, and do not change the text. Please include a link back to the original article.

We put an invisible pixel in the article so that we can count traffic to republishers. All analytics tools are solely on our servers. We do not give our logs to any third party. Logs are deleted after two weeks. We do not use any IP address identifying information except to count regional traffic. We are solely interested in counting hits, not tracking users. If you republish, please do not delete the invisible pixel.