City evicts recently housed Wolwerivier families

Dozens of Metro Law Enforcement officers swooped on Wolwerivier relocation camp on Wednesday morning. They broke locks and ejected two households deemed to have occupied the municipal built structures unlawfully. Yet, a community leader has called this show of force an insult, citing the general lack of safety and protection for Wolwerivier’s inhabitants.

Eighteen-year-old Sive Ndinise was at school when contractors for the Anti-Land Invasion Unit (ALIU) broke the lock to her home, carried out her possessions — a table, plastic chairs, a mattress, a suitcase and a few kitchen utensils — and loaded these onto a truck. Once the structure was emptied, a new lock was attached to secure it.

The ALIU have set up a mobile unit at the settlement — a municipal built relocation area for families cleared off land needed for development. The City of Cape Town has tasked two law enforcement officers, along with a private security company, to protect completed — but unoccupied — structures from “invaders”.

According to officers on the scene on Wednesday, they had been instructed to remove households deemed to have “unlawfully” occupied houses at Wolwerivier.

Wolwerivier. Photo by Shadi Garman.

But community leader Thozama Qobongwana says that Ndinise was a legitimate beneficiary who had relocated along with Skandaalkamp’s 250 other families to Wolwerivier earlier this month. Skandaalkamp was an informal settlement adjacent to the Vissershok landfill site off the N7. The community were relocated as a precondition for the dump’s extension.

“[Ndinise’s] grandmother was the original beneficiary. But she passed away before the move and we did not want her grandchild to be without a home. So we helped with all the paperwork to ensure that she could also stay within our community. The City itself helped to move her furniture here and to get her instated. Now she is evicted just like that, without warning,” said Qobongwana.

Mayoral committee member Benedicta van Minnen however remains adamant that the two households evicted by the ALIU had illegally invaded the structures and had not signed the requisite occupational agreements with the City. To Qobongwana’s complaints, she responded that City would investigate if the community could provide more information.

“The probability of a wrongful eviction however is low, as the Informal Settlements Management staff knows exactly which units were allocated to specific beneficiaries,” she said, adding that the City was under “no obligation” to make alternative provisions for the “illegal” dwellers.

“They need to go back to their original places of residence,” van Minnen said.

But Skandaalkamp no longer exists; it has been demolished, so there is nowhere for residents to return to. The move from Skandaalkamp, and the allocation of units to households from there, appears to have allowed some residents to fall through the cracks. In one of the units I inspected, two Skandaalkamp families — 4 adults and six children — were apparently sharing the 24m2 floor space to sleep at night. There is over-population of this sort throughout Wolwerivier, says Qobongwana, which has led to general resentment and a desire for more units to become available for Skandaalkamp’s people.

In another instance, 53-year-old Nzimeni Mayekiso — a resident of Skandaalkamp of 25 years — says he was excluded from the list of beneficiaries because he was ill and being cared for by a family member elsewhere when the allocations of units were made. He was still spending his nights on the floor of the security hut at Wolwerivier two weeks after the move in early July.

“I have no structure in Skandaalkamp anymore, because it was broken down along with the others. But, I have no place in Wolwerivier either, so I am very concerned because the security guards will not let me stay there forever,” he said.

Finally, Qobongwana went on to complain that the City and Law Enforcement were “abusing” people, while failing in the task of making Wolwerivier safe and secure for the new residents. She pointed to two incomplete projects: the lack of streetlights and the incomplete perimeter fence meant to secure the settlement.

“Children can get raped and murdered by skollies in those bushes because there is no fence,” she said.

“And, at night it is pitch dark and no one can see anything outside. This is a perfect environment for criminals to operate in. Instead of spending money to fix these, the City sends so many officers and trucks simply to evict someone who is part of our community.”

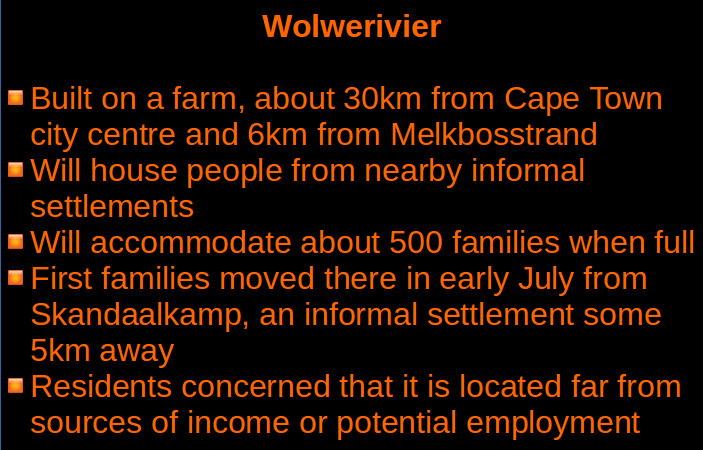

Google Map of location of Wolwerivier. It is located next to the M19, after you turn off the N7.

For GroundUp’s previous coverage of Wolwerivier relocation please follow these links:

Support independent journalism

Donate using Payfast

Don't miss out on the latest news

We respect your privacy, and promise we won't spam you.

Next: Deputy minister swaps his T-shirt for sanitary pads

Previous: Children without homes: referrals up for Cape Town centre

This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.