Farewell to a lovable revolutionary

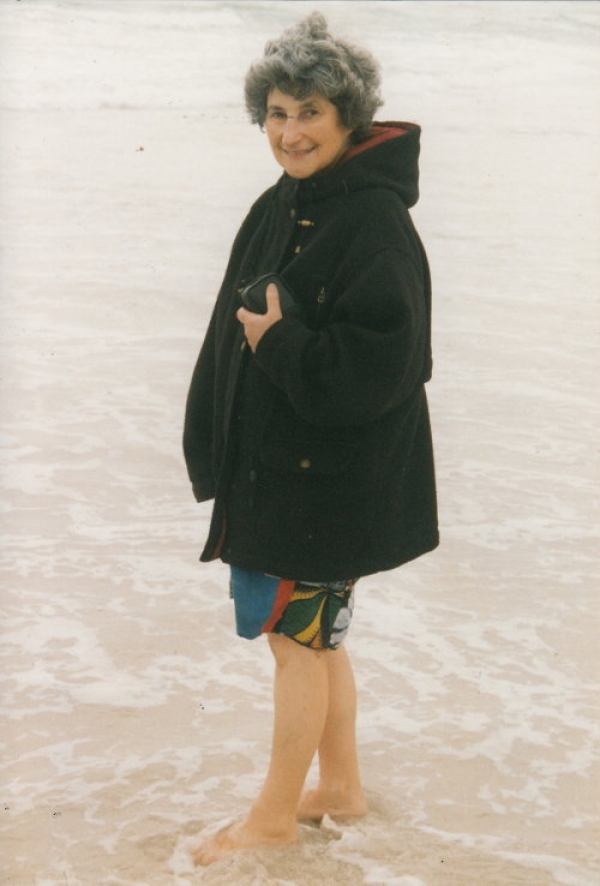

Sadie Forman (1929-2014) one of the most unconventional, interesting and lovable fighters in the South African anti-apartheid movement, died on the morning of 11 December, aged 85. She spent the last years of her life with her daughter, Sara, in Lewes, in the East Sussex county of England. Her funeral will be held on 23 December.

Sadie relocated to England in 2007 on health grounds, after spending nearly a decade working as a volunteer in the library and archives at Fort Hare University. She returned from exile to take up the position, having retired as a primary school teacher in England where she had been in exile since 1969. In 2012, she returned briefly to Fort Hare to receive an honorary doctorate in the humanities.

Sadie married Lionel Forman, perhaps one of the brightest stars in the South African anti-apartheid and Communist movements, in 1952. Four years later, Lionel was one of the 156 men and women in the marathon treason trial that began in 1956. Sadie provided essential back-up to Lionel whose failing health saw him die in 1959 on heart transplant pioneer Christiaan Barnard’s operating table. An advocate, historian, activist and prolific writer, he was just 32. By then, Lionel and Sadie’s third child, their daughter, Sara, was just five days old.

“Yet I had to earn a living,” Sadie noted in her 2008 memoir, Lionel Forman — A life too short. That was easier said than done, because not only did police harassment continue, but she was served with a banning order. Subject to police permission, she was restricted to a “one mile” (1.6km) radius of her home and forbidden to enter “any factory premises or educational institution.”

When fellow activist and print shop owner, Len Lee-Warden offered her a job as a proof reader, the police finally relented, but only on condition that she be housed in an enclosed office, and that only one worker at a time could enter to deliver or remove proof copies of the publications she read and corrected. Any breech of these conditions could result in a prison term.

The stress was starting to tell, compounded by news that a friend in Johannesburg, Babla Saloojee, had died, having “fallen” from a seventh floor window of a Special Branch interrogation room. Some other political families had also left for exile. She had no money, but the cottage in Camps Bay she and Lionel had bought years earlier has appreciated greatly in value.

Having been denied a passport, Sadie applied for an exit permit that entitled her to leave on condition that she never return and sold the cottage. But then she had second thoughts, feeling she was deserting the many comrades and friends who could not afford to leave. This meant that she had then to apply to stay and to live elsewhere since Camps Bay was now financially out of her reach. As she put it: “After much parleying with the Special Branch, I was given permission to look for a house outside of my restricted area.”

She moved to Wynberg. But the harassment continued. And then came the final blow: a new regulation made it imperative for all proof readers to pass a compositor’s examination by the end of 1969. This entailed work on the factory floor which, as a banned person, she could not do. The time requirements also meant it would be impossible for her to qualify.

Unemployment loomed. “I was also certainly unemployable elsewhere in South Africa,” she wrote. The time had come to leave. And when she again applied for an exit permit and was told: “If you don’t go this time, you will not get another one.”

Sadie Forman, together with children Karl, Frank and Sara set up home in London where Sadie qualified as a primary school teacher and later gained a second degree, this time in psychology. Fiercely non-sectarian, outspoken and with a keen mind, she was also a notoriously bad time keeper, resulting in her many friends affectionately referring to her as “the late Mrs Forman”. A member of the ANC Women’s League and campaigner on human — and especially women’s — rights, she maintained an open house for exiles passing through England.

A seriously loyal friend, she was generous almost to a fault, with both her time and resources. She also had a deserved reputation for speaking out against perceived injustices, even within an ANC to which she remained firmly attached although increasingly — and constructively — critical of it and its leadership over the years.

Utterly unawed by pomp, circumstance and position, she famously — and loudly — advised Ireland’s Sin Fein leader Gerry Adams at a conference about Irish negotiations: “Gerry. Don’t you make the same mistakes we did.”

Petite, charming and armed with a fount of jokes, she arrived at Fort Hare University in 1996 and fell in love with the village of Alice, one of the very few staff who actually stayed in the town. Over the next decade, she became something of an Alice institution herself. And, even when her health was failing and her memory beginning to let her down, she did not want to leave.

Finally prevailed upon by her daughter, she reluctantly returned to the place of her exile. The words of fellow activist and friend, Douglas Maquina, who wrote (in isiXhosa) of Lionel when he died that he was “a small man, but….as big as Table mountain” apply equally Sadie: She was a small woman, but certainly as big as Table mountain.

Support independent journalism

Donate using Payfast

Don't miss out on the latest news

We respect your privacy, and promise we won't spam you.

Next: What immigrants do in the holidays when it’s too expensive to travel home

Previous: Hope Street carpenter shut down

Letters

Dear Editor

My Mother, Sadie Forman was certainly a political giant. She never seemed to stop working. Not just for her children but for the struggle against apartheid. She worked tirelessly at the university of fort hare library on the archives of the ANC.

Mom I love you dearly

Hamba Kahle Sadie Forman

Amandla Ngawethu Power to the People

Aluta continua

This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.