Grabouw: “We are sitting here, lost”

Siyanyanzela residents face uncertain future

It’s around 9am on a chilly, overcast morning, Friday 13 May. Grabouw’s Siyanyanzela informal settlement is calm after days of clashes between residents and law enforcement officials.

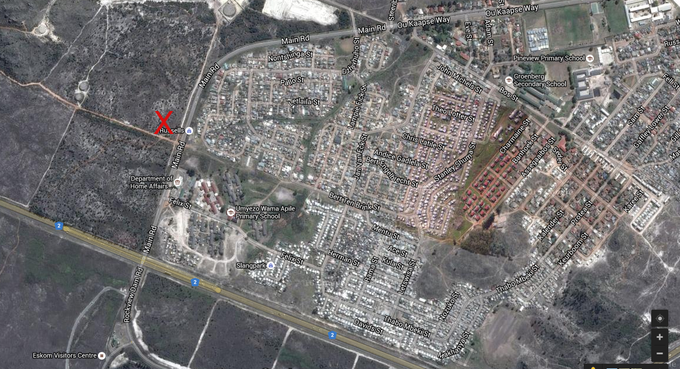

Atwell Noqha is sitting on a rock, dressed warmly. Behind him is his shack, marked with a big red “X” next to the door. Near him are the ruins of other shacks, with residents trying to salvage what they can of their belongings.

For several days, residents have been protesting over the demolition of their shacks, built in March on this land, which belongs to the department of Public Works.

On Friday morning in the Western Cape High Court, Judge President John Hlophe granted the Minister of Public Works an interim interdict against the occupation of the property. The order authorises the Department of Public Works to demolish any structure erected on the property after the granting of the order and to remove the possessions, including building materials, of those who move in. These possessions are to be kept in “safe custody” for three months until released to their owners.

In terms of the order, the court will determine when people already occupying shacks on the property must leave.

Police are authorised to remove anyone contravening the order.

“It’s tough, sisi. We are sitting here, lost. We do not know what is going to happen,” says Noqha. “It’s quiet now. I am one of the people whose home was not demolished, but no one knows what will happen today.

“Look, these people are constantly watching us, ready to do anything,” he says, pointing to a police Nyala on the other side of the N2, which had been blocked during protests earlier in the week in which vehicles were set alight and the traffic department burned down.

“We don’t have anywhere to go. That is why we are here. Most of us come from the Eastern Cape. We are unemployed and cannot afford to pay rent any more as backyarders,” says Noqha.

Noqha says unrest in Siyanyanzela, which means “we are forcing our way in”, started on Monday 9 May, when law enforcement officials started demolishing the shacks.

A few metres away, Nosandise Jezu is rummaging through her demolished shack, hoping to find undamaged material that she can re-use. She is unemployed and hoped to move to Siyanyanzela with her family from Vezinyawo township in Grabouw, where she, her husband and two children share a house with four other people, and where she is paying rent of R500 a month.

“They tore my house down yesterday (Thursday) but luckily I had not moved my things from where I am renting to here. I was going to do so today. So it was just a vacant shack.”

Nearby, Momelezi Seyiwa and his partner Thembisa Tayi are putting up their demolished shack again, using whatever material they could save. Lindelekile Ntlila, who was living in his shack when it was demolished, is trying to find his suitcase in the debris.

Suddenly residents start shouting: “Here they come again”. Law enforcement officers can be seen walking down the road heading to Siyanyanzela.

Following them are a large number of men wearing yellow or orange bibs, carrying tools like hammers and an electric saw. As we watch, they move into the settlement and start collecting the material from the demolished shacks, making sure that the material has been completely destroyed by hitting and bending it with tools.

Residents scramble to guard what is left of their shacks. Others carry the corrugated iron structures to the opposite side of the road. Law enforcement officers can be heard stopping other residents from entering the area. Big trucks stop on the side of the road and the materials from the demolished shacks are loaded onto the trucks to be taken away.

Wearing a red overall, a man who introduces himself as coming from the Department of Public Works writes down the names and contact numbers of residents whose shacks, like Noqha’s, are still standing but marked with a red “X”.

He says: “The structures that have an ‘X’ on them must all give me their details. The X means that your structure will not be demolished, meaning you can continue living in it until such time as you get a call from public works informing you to remove it and find alternative accommodation.

“Until then, no one is going to demolish your structure or tell you to leave”.

Grabouw is part of South Africa’s largest apple and pear production area. It has three large fruit packing factories, and it is also home to an Appletiser manufacturing plant.

The number of shacks along the N2 has mushroomed over the past two decades. Between the 2001 and 2011 censuses Grabouw’s counted population grew from 21,953 to 30,337, a rate just shy of 3.5% per year. By comparison, Khayelitsha grew by just under 2% per year, and South Africa’s population growth rate is about 1.3%. While there are no recent population statistics, Grabouw appears to have grown substantially in the past five years, with people moving in from other parts of the country, or from nearby farms from which they have been evicted.

Grabouw is part of the Theewaterskloof municipality. Although the official unemployment rate is lower than the rest of the country, at just under 15% it is still high.

According to the municipality 222 houses were provided in the past financial year. R36 million is being invested in the town’s informal settlements this year.

According to Nathan Adriaans, communications director at the Western Cape Department of Human Settlements, the three spheres of government “will collaborate on the long term solution to the housing problem in Grabouw”.

Adriaans said most of the land which could be used for housing in Grabouw “falls under the custodianship of the Department of Public Works”.

Funds were also needed to provide services such as water, sewerage, electricity and roads, Adriaans said.

He said questions about Grabouw were best answered by the national department, which had not responded to GroundUp’s questions by the time of publication.

Support independent journalism

Donate using Payfast

Don't miss out on the latest news

We respect your privacy, and promise we won't spam you.

Next: Marx and the search for alternatives

Previous: Bread and jamming: a different approach to homeless people in Observatory

© 2016 GroundUp.

This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

You may republish this article, so long as you credit the authors and GroundUp, and do not change the text. Please include a link back to the original article.