John Fredericks: “I’ve been labelled a skollie all my life”

Author talks about how his acclaimed movie is helping to change lives on the Cape Flats

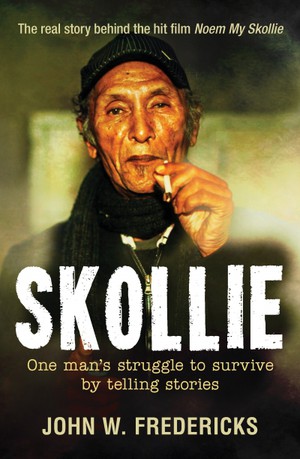

“I wanted to rise above the stigma of prison and gangsterism that had become my heritage,” says 71-year-old John Fredericks as he puts out his cigarette.

The scriptwriter of well-received documentaries, such as Mr Devious and Hard Living Kids, is best known for the film Noem My Skollie directed by Daryne Joshua. Seen by over 90,000 people in cinemas countrywide, it has won many awards. Based on Fredericks’ life story, growing on the Cape Flats in the 1960s, it tells the story of four young boys who started a gang and ended up in jail. Fredericks, who grew up in Kewtown on the Cape Flats, says he worked on the script for 14 years, mostly using an old typewriter his father found at a dumpsite where he also spent a lot of time as a child looking for books to read.

GroundUp met Fredericks and his wife, Una, at their home in Strandfontein. On Sunday, 17 September, Fredericks will launch his autobiography, Skollie, at the Artscape Theatre with a “one time only” screening of the film being accompanied by a live orchestral performance by composer Kyle Shepherd.

His publishers at Penguin Random House gave him a six month contract to write 82,000 words in 26 chapters, he says. “But Una was a bit nervous because I would be working with one less finger and eye!” he says. Fredericks lost the sight in his left eye two years ago.

“While I was waiting for my notes to come back on the script, something happened to my laptop. I didn’t save my work … so I lost almost 100 pages. It took two months to fix the laptop again, so in the meantime, I wrote the story out on paper from my memory,” he says.

Fredericks says he managed to finish the book in four months while also having to translate the full feature film from English to Afrikaaps.

“This is why I left my day job as a security officer when I was 50. I had a few jobs before that, but I was never happy. In my quiet times, I would always be writing and telling stories,” says Fredericks.

Dressed in black, Fredericks is seated behind a small desk in a room which has become his workspace with several of his accolades and posters of his works displayed on the walls.

He recalls the day nearly 20 years ago that he decided to “share his story”. “I was still a security guard when someone asked me to go with them to Pollsmoor Prison. Going as a civilian was a strange feeling because I helped lay the foundation there. As I walked in, I saw all the kids sitting there, some still in school uniform. I could identify with them because I was just 16 years old when I went there,” he says.

“That’s when my mother’s words echoed with me that I have a higher calling. The next day, I looked at the beautiful blue gum tree outside my security guard office and told myself that I can’t look at that tree for one more month.”

Since the film’s release in September last year, Fredericks has been invited to speak at a number of schools and events. The father of five recalls his first “heartbreaking” interaction with a primary school pupil in Delft.

“One of the teachers contacted me because of the number of children killed there. I asked a few artists to accompany me. I laughed when all of those children [in the hall] raised their hands when I asked who watched the movie [Skollie] because of the age restriction. A boy came to me crying bitterly and hugged me.

“When I asked what was wrong? He said ‘uncle you just changed my life’ and I knew then that he was molested. It happens every day, but people still don’t talk about it,” he says.

Another turning point in his work was when he was invited by Linton Japhta to what he was told would be a special screening of Fredericks’s film in Paarl. To his surprise, when he arrived there were high ranking police officials and staff from the Drakenstein and Pollsmoor prisons. “These are the people I generally try and avoid. But that night everyone was asking to take photos of me,” he says laughing.

“I went into the cinema while everything was dark. As the movie continued I heard the giggles in the cinema became quieter and quieter. When it ended, I went on stage and the lights went on. It was a theatre full of gangsters, young and old. I just spoke to them from the heart. After, a guy came to me and asked, ‘uncle how can I change?’, I looked at him for a moment and told him it was for him to decide who he wanted to be.”

Fredericks says Japhta contacted him the next day to inform him that the leader of the Barbarian gang had “decided he was finished with that life” after watching the film.

“My heart felt like it was in my throat … He has matric and we discovered that he is a talented playwright and rapper. Once you’re a gangster, there’s no way out. But Noem My Skollie took him out. He now has a job after being trained as a barber. That whole gang disbanded and is now working in and around Drakenstein prison as youth activists. Some of them even went back to school,” he says.

Fredericks has become an ambassador for the group and has featured them in his book.

Over the years, he has given many writing workshops for prisoners. “When you work in prisons, you can’t just go in there and preach to them. These are killers, rapists and thieves. So I meet them in the mind and teach them to write and tell their stories. I’ve found kids with grade 10 who can’t even write or spell,” he says.

“I ask them to go back to the time before they got that knock on the door from the police. I get them to laugh about their childhood days. I then ask them to describe the day they got arrested using all five senses. You will be shocked with what they write. One day a new guy came into my workshop. Everyone was afraid of him, he was full of tattoos, a 26 [gang member]. His story blew me away,” he says.

“Skollie has become a movement,” says Fredericks. But not everyone has responded to his work positively. “I went on Cape Talk [radio] this week. There were a few negative responses from listeners asking how they could have a convict on the show. But this is my life. I’ve been labelled a skollie all my life. People are so quick to complain about crime and violence, but then they go home and hide behind closed doors. I want to challenge them: what are you doing to make a difference?” he says.

Fredericks jokes that a holiday was not on the cards for him as “there was still a lot of work to be done” as he has “a room full of completed scripts”.

“We need to help those kids who are already on the road to hell. As young parents, our children should be our priority and know what’s going on in their lives. My children are all adults now, but they know that I made sure they had what they needed,” he says.

Fredericks laughs as he recalls being stopped by strangers in the street asking him to pose for a photo with them. “I was a nobody. People who have lived near me for years also come to me and ask me to sign [autograph]. Why not? People knew me, but never knew my life story,” he says.

“When people invite me to an event, my daughter always says don’t ask my dad to make a speech because he will make a documentary.” He laughs.

Tickets for the launch on Sunday afternoon are still available at Computicket at R150.

Support independent journalism

Donate using Payfast

Don't miss out on the latest news

We respect your privacy, and promise we won't spam you.

Next: Learners in Limpopo town unable to write exams

Previous: Police confirm investigation into shooting of Ona Dubula

© 2017 GroundUp.

This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

You may republish this article, so long as you credit the authors and GroundUp, and do not change the text. Please include a link back to the original article.