HIV drug studies offer patients more choices

But new regimens are not problem-free

When it comes to treating HIV, we are spoilt for choice. That’s perhaps the only clear message that comes from three studies, all conducted in Africa, whose results have just been published by the prestigious New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM) and presented at the Mexico AIDS conference this week.

Studies in South Africa and Cameroon compared three antiretroviral regimens for treating HIV. The bottom line is that all had excellent results, and that you need a statistical microscope to differentiate between them.

The standard treatment regimen offered to people newly diagnosed with HIV in South Africa consists of the three drugs: tenofovir (TDF), emtricitabine (better known by its abbreviation FTC) and efavirenz (EFV).

In recent years two new drugs have been developed which clinicians believed may be better alternatives than TDF and EFV: a new smaller version of TDF, known by its abbreviation TAF, and a drug called dolutegravir (DTG) to replace EFV.

Although TDF and TAF are quite similar, DTG is a different class of drug to EFV. DTG attacks an HIV enzyme called integrase, while EFV goes after an enzyme called reverse transcriptase.

The South African study, called ADVANCE and led by Wits University’s Dr Francois Venter, compared three regimens: TDF/FTC/EFV (i.e. the standard regimen) vs TDF/FTC/DTG (DTG group) vs TAF/FTC/DTG (TAF+DTG group). Each group had 351 people.

The standard regimen is good and affordable, with few side-effects compared to the antiretroviral regimens used in the 2000s in South Africa, so why the need for more treatment regimens? There are two reasons.

First, the TAF and DTG were suspected to have fewer side effects than TDF and EFV. In some patients EFV causes psychological side-effects, like bad dreams or whooziness.

Second, EFV has been in use a long time and so inevitably there are some HIV strains in the population that are resistant to it (which means EFV is no longer effective against those strains of HIV). DTG is hardly used in South Africa and so there is almost no HIV that is resistant to it here. But DTG is also a harder drug for HIV to become resistant to.

After 48 weeks, the percentage of patients whose HIV could no longer be detected in their blood was 79% in the standard regimen group, 85% in the DTG group and 84% in the TAF+DTG group. In technical jargon this means that the DTG and DTG+TAF groups were non-inferior to the standard regimen. While they do seem to have had a slightly better result, it isn’t considered a big enough difference that it can’t be explained by chance. Also, the participants on the DTG and DTG+TAF groups raced to having undetectable virus faster than the standard group, which is good.

To get a sense of how well patients did, there were only four deaths out of the 1,053 people on the trial. In the early 1990s, when antiretroviral treatment was in its infancy, this would have been impossible.

There were slightly more adverse events in the standard regimen group. But all three groups had very few serious side-effects.

There was one concerning finding though on the DTG group and especially the DTG+TAF group. The participants, especially women, put on weight. That might not sound like a problem. And in fact, the propaganda of the diet industry aside, being a bit podgy, e.g. having a BMI between 25 and 30, is no bad thing.

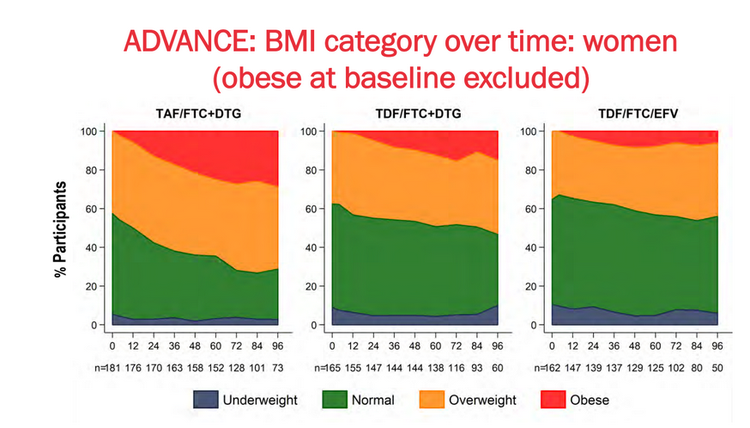

But the problem is that quite a lot of people on the trial became obese (BMI greater than 30), as the graph below shows. And it appears that DTG+TAF exacerbates the problem. This increase in weight using DTG was also seen in the Cameroon study (which didn’t have a TAF group).

The increased obesity finding is concerning. Obesity is associated with increased risk of diabetes, alzheimer’s disease, hypertension and about four-years lower life-expectancy. But some perspective is needed: it wasn’t too long ago that this would have been a “1st-world problem”, as the saying goes, for people with HIV.

Moreover, 157 women and 93 men were questioned about the change in weight they experienced. 193 reported being happy with the weight change, 22 were indifferent, and 35 were unhappy. Of this last group, 11 were unhappy due to loss of weight, not gain. Of the 20 people who gained a very large amount of weight (more than 20% of their body weight when they started the trial) only two were unhappy about it.

In the ADVANCE study, people taking TAF were more likely to become obese than people on the standard regimen. By the end of the study the gain in weight on the DTG and DTG+TAF group had not plateaued.

Does DTG cause a serious birth defect?

There is however one very serious possible side-effect associated with dolutegravir that was suggested by some preliminary data from Botswana a few years ago. The third study published in the NEJM finally provided substantial data on this.

Previously the babies of women who took dolutegravir in the first trimester of pregnancy appeared to have a slightly higher risk of having a neural tube defect. This often results in the child dying or being disabled.

Now a lot more data has come out of Botswana: Out of 1,683 women who were taking DTG at conception, five babies were born with neural tube defects, 0.3%. By comparison in nearly 15,000 deliveries from women on antiretroviral regimens not containing DTG at conception, there were 15 babies born with neural-tube defects, 0.1%.

While there is a higher rate of neural tube defects associated with DTG, the numbers are extremely small, and we don’t know if there’s a causal relationship.

Part of the problem with a finding like this is that people cannot predict when they will conceive (there are no known concerns with DTG after the first trimester). So there’s not much practical effect of warning women not to take DTG when conceiving or in their first trimester of pregnancy.

The concerns with DTG and TAF — i.e. the possible tiny additional risk of one’s baby being born with a neural tube defect if taking DTG, and the weight gain associated with both drugs — have to be weighed up against the side-effects of EFV and slightly increased risk of resistance. But compared to the treatment options of a little more than a decade ago, people with HIV today are far better off and have multiple good options.

Support independent journalism

Donate using Payfast

Don't miss out on the latest news

We respect your privacy, and promise we won't spam you.

Next: Residents of apartheid-era shack town still have no electricity or toilets

Previous: Social Development Department didn’t know it had offices in Alexandra

© 2019 GroundUp.

This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

You may republish this article, so long as you credit the authors and GroundUp, and do not change the text. Please include a link back to the original article.