“How do you expect 550 boys to share six toilets?”

The bell rings for break time, triggering a mad rush for the toilet. Many learners won’t make it in time. After all, “how do you expect 550 boys to share six toilets … when there is only one break?”

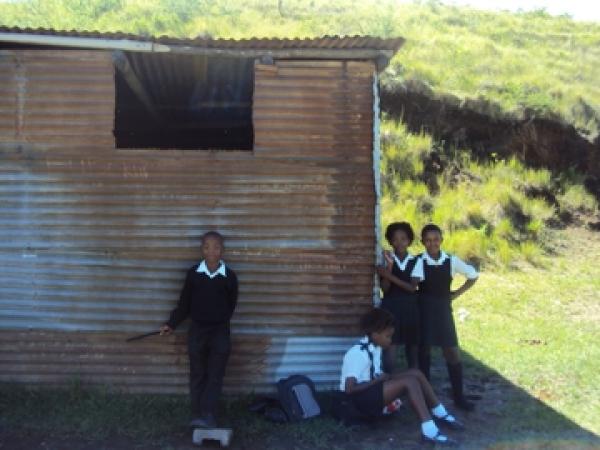

A learner struggles to concentrate as the wind whips against the walls of his classroom, which is “not safe as they could fall any time.”

A learner approaches a man who has easy access to his school because it does not have a proper fence as “people from our community [can] come and sell drugs to learners”.

These quotes were gathered by Equal Education (EE) during countrywide workshops it organised on the latest set of draft norms and standards for school infrastructure. The draft was released for public comment by Minister Angie Motshekga on 11 September 2013.

On Tuesday 19 November, World Toilet Day, EE released the results of its survey of high school toilets in Tembisa, Gauteng. The survey was conducted by EE members over two weeks, and included eleven of the fourteen high schools in the area.

At over half of the schools surveyed, more than 100 boys and girls had to share a single working toilet. On some days there were no working toilets for boys or girls. Many of the schools had broken taps, and sometimes there was no water supply.

Many learners felt violated and unsafe because of a lack of doors or locks on doors. As one learner said, “My dignity is not there any more because of the dirty toilet I have to go to every day.” The survey brought home the fact that poor school infrastructure is not limited to provinces like the Eastern Cape and Limpopo, but that it is a national problem, requiring a national response.

Many learners felt violated and unsafe because of a lack of doors or locks on doors.

This is what norms and standards for school infrastructure are. Once adopted, norms and standards will establish a minimum infrastructure standard for all public schools. This will oblige provincial education departments to provide water, electricity, proper toilets and classrooms to schools in need, and empower learners and parents to hold them accountable for doing so.

The current draft norms and standards, released by Minister Motshekga in September, flow from a court order secured by EE represented by the Legal Resources Centre (LRC), and agreed to by the Minister, in July this year. The order followed the Minister’s failure to finalise norms and standards by 15 May, as she had previously agreed to do.

Brad Brockman is the General Secretary of Equal Education.

It also came on the heels of mass marches EE organised in Pretoria, Cape Town and Bhisho, to which the Department of Basic Education shamefully responded by racially attacking EE as “a group of white adults organising black African children with half-truths”, and as “opportunistic, patronising and simply dishonest.” The Minister has refused to retract or apologise for these statements.

Yet the court order stands, and by 30 November the Minister will have to adopt legally binding norms and standards. The current draft is also substantially better than the draft released by the Minister in January, which lacked content and time-frames and was essentially meaningless.

However, there are at least two serious deficiencies with the September draft. The first is that its timeframes for implementation are too long, and the second is that it does not require provincial education departments to make their implementation plans and annual progress reports publicly available.

A problem with the draft norms and standards is that it does not require provincial departments to make their implementation plans public.

According to the draft, water, electricity, proper toilets, classrooms and fencing should be provided to schools within ten years; libraries, laboratories, sports and recreational facilities and electronic connectivity within 17 years.

This is simply too long to wait, especially for learners in the worst off schools. As a learner at a school in rural Kwa-Zulu Natal said in her submission on the draft, “in our schools we have urgent issues that can’t wait ten years before it is achieved.”

Also, without short and medium-term timeframes, it will be difficult to ensure consistency in delivery and track provinces’ progress in implementing the norms. A parent from Khayelitsha in the Western Cape therefore requested that “the ten year target be reduced, so that each and every year there are targets and there are improvements made in schools.”

There is also a legal argument to be made for shorter time-frames. The Constitutional Court has held that the right to a basic education is “immediately realisable” and not subject to “progressive realisation”, as is the case with other socio-economic rights. Central to this is the provision of safe and adequately resourced schools for all.

And while this cannot be done overnight, government does have an obligation to do all it can to realise this right. This means prioritising the building of schools above stadiums and government members’ private residences and the purchase of arms. Crucially, it also means making available the human resources, management and expertise necessary to deliver large infrastructure projects.

The current draft requires MECs to draft plans for implementing the norms within six months after these are adopted, and to report annually on their progress. However, MECs are only required to send these plans and reports to the Minister, and not to make them publicly available.

This would leave schools in the dark, as well as the public. Principals would not know if and when their schools were due for an upgrade, and we would not know how provinces were doing in implementing the norms and standards. This is bad for transparency, accountability and ultimately democracy.

We look forward to Minister Motshekga adopting quality norms and standards by 30 November, with shorter time-frames and a requirement that MECs make their implementation plans and progress reports publicly available.

Support independent journalism

Donate using Payfast

Don't miss out on the latest news

We respect your privacy, and promise we won't spam you.

Next: Where politics gets really smelly

Previous: Black Widow Society: an extract from Angela Makholwa’s latest book

This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.