“I called the police many times but they never came”

What victims and perpetrators of Soweto’s xenophobic violence say

When parts of Soweto erupted in xenophobic violence on 29 August, members of the community in and around the sprawling Meadowlands hostel joined in the rampage and destroyed every one of the 20 or so immigrant-owned food shops that had served them.

Meadowlands Zone 11 is dominated by a hostel from the apartheid era: 740 rows of barrack-like buildings.

Built in the 1950s to accommodate single men who came as cheap labour from the rural areas, the hostel was perceived as being an Inkatha stronghold pre-1994 and there were violent confrontations, including gunfights, with the surrounding community. Today the 4,444 two-room units with built-in cement beds are crammed with families. Shacks have also sprung up between the barrack rows and in every bit of space.

Surrounded by the better-off suburbs of Killarney and Mzimhlophe, with their tarmac roads, neat RDP houses and landmarks like Meadowlands Mall, Vilakazi Street and Orlando Stadium, the hostel is a derelict place, with its dusty streets, long drop toilets, piles of stinking uncollected rubbish – and a lot of crime.

Ali Hamid in his supermarket the day before it was gutted. “We gave the community 100 soft drinks and bread for protection from the thugs,” he says.

Ali Hamid is the 25-year-old owner of a small supermarket serving the hostel community. Only the day before the 29 August violence he was complaining that he was losing business as suppliers had refused to continue bread deliveries to him.

“In May a Sasko bakery truck was robbed right here at the entrance to my shop,” Hamid said. “We called a community meeting regarding the crimes we are experiencing here. We gave the community more than 100 soft drinks and bread for free for protection from the thugs in return.

“But nothing has changed. We are still victims of crime. Now Sasko and Sunbake are scared to deliver bread and I am losing business.”

Within 24 hours Hamid’s supermarket, opposite the Ekuthuleni hall, was gutted and Hamid and the rest of the other immigrant-owned businesses around the hostel had piled into their bakkies and fled for their lives, escorted out of Soweto by police. Today Hamid is recovering from his loss in the more immigrant-friendly suburb of Mayfair, close to the Johannesburg city centre.

Even before 29 August, residents in Meadowlands Zone 11 lived on the edge, frequently mugged at knifepoint for cash and phones. Mondli Zondo, aged 38 and a South African citizen from KwaZulu Natal who lives in Orlando West, was mugged at gunpoint by two men one night after getting off a taxi from Johannesburg. “They took my new Samsung J23 smartphone and ran away,” says Zondo.

“I didn’t go to the police and open a case. I went to a sangoma and now the izigelekeqe [thugs] will pay for what they did. When the sangoma’s magic starts working they will come back to me and beg for forgiveness.”

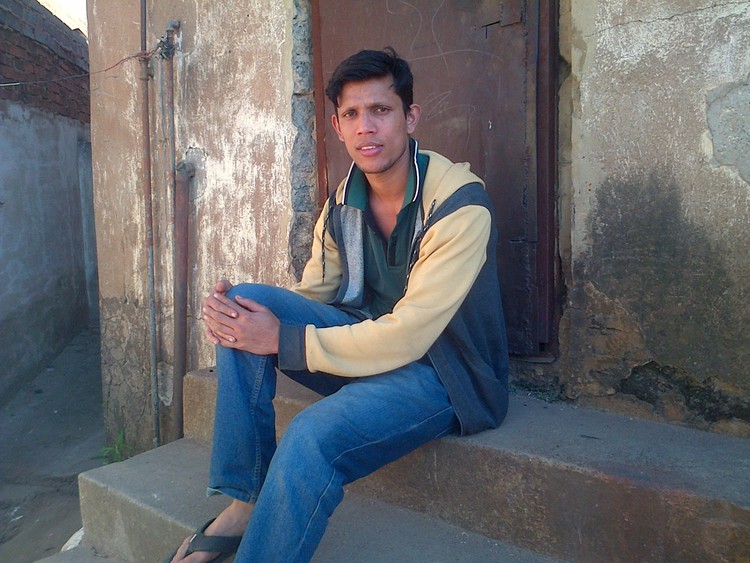

So who is doing the crime in Zone 11? One of the pair who mugged Zondo lives in a shack in the lee of the Meadowlands hostel with his wife and two children. Gonondo (not his real name) is 28, neatly-dressed in ghetto-wear. He wears a blue hoodie and jeans and top of the range brown leather boots. In a scrapey voice he says he’s unemployed and makes ends meet by robbing immigrant-owned supermarkets and anyone foolish enough to brandish their cellphones in the street.

Gonondo, a mugger, says, “I target foreigners…they don’t belong here.”

The mugger says he had a two-year spell as a casual worker in retail stores. “I was earning peanuts, which was not enough for me to pay crèche fees and feed my family. Doing crime is a risk I must take for my family. I don’t rob black-owned supermarkets – they can easily get me arrested – only those operated by foreigners.”

“I target foreigners because they have what I need – money – and they don’t belong here in our neighbourhood. I would really like to live a normal life, work and earn a decent salary to take care of my family. The robberies I commit do haunt me sometimes. I take from poor people who are in need like me. What keeps me going is seeing my kids happy,” he says. “I didn’t choose to be thug, circumstances led me to this life. I rob to feed my family.”

Another victim – not one of Gonondo’s – is Ibrahim Mohammed, a 21-year-old from Malawi who worked at an immigrant-owned supermarket in Meadowlands until it was stripped bare on 29 August. Mohammed’s been mugged and lost five cellphones in nine months. The last time he was going back to the supermarket from the new BP garage nearby (it’s already been robbed several times) when he was jumped by six thugs. Members of the public enjoyed the spectacle and didn’t intervene, leaving Mohammed to stagger into the supermarket in tears.

“Reporting the matter to the police is a waste of time,” he says. “I just buy another phone to keep in touch with my family in Malawi.” He adds: “Where I come from we are facing economic problems, but not robbers.”

This immigrant-owned shop was gutted.

A woman living in the hostel looks back to the night of 29 August, when an immigrant-owned supermarket next to her building came under attack. “I heard gunshots and people making noise. I switched off the lights so I could see what was happening in the yard. Looters ripped the burglar bars from the supermarket doors and cleaned out the goods. Within 15 minutes everything was gone – food, fridges, shelves and electric wiring.

“Now the place looks like an old abandoned hall with what’s left of soup ad banners on the roof top,” she says.

Still in business is Mohammed Hossain’s shop, well away from the hostel next to Mzimhlope station in Orlando West. Hossain is 24 and comes from Bangladesh. Known as Bongz, he is adored by his customers because he speaks fluent South Sotho, Zulu and Tswana.

Hossain arrived in South Africa when he was 14 and lived in Rustenburg where his father had a supermarket. He doesn’t remember any xenophobic attacks there. “The community in Rustenburg is very strict, no one was allowed to loot,” he says.

We spoke the day after the xenophobic attacks. “I called the police many times yesterday, but they never came,” says Hossain. “I usually give them a ring and communicate with them. They know who I am. But yesterday they kept on asking me irrelevant questions as if they don’t know who I am any more.”

“I’m tired of wasting my airtime. The police only come here when they are thirsty for my soft drinks which I give them in return for protection which I don’t get. They come here without money and I give them a drink of their choice. If I refuse they make threats, telling me that xenophobia is coming and they won’t protect me and I shouldn’t even bother to call them,” he says. “Yesterday when the trouble started I gave local community lads money and told them to protect my shop for the entire night. I am glad they managed to fend off a mob of looters who tried to break in.”

We put Hossain’s allegations to SAPS. Colonel Lungelo Dlamini of the Gauteng Media Center said, “These are serious allegations that must be investigated. If possible the victim should submit a statement so that members involved can be investigated.”

The latest outburst of violence in Soweto, which claimed three lives, was apparently triggered after a Somali shop owner was accused of shooting a teenager and his friend who allegedly tried to break into his store. Residents also complained that immigrant shop owners were selling expired food.

“Not all of us are selling expired food,” says Hossain. “I would like inspectors to visit all foreign-owned shops and arrest those who are breaking the law. The government must make our safety a priority. Our lives are in danger.”

Schoolchildren scavenge in a burnt out supermarket.

© 2018 GroundUp.

This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

You may republish this article, so long as you credit the authors and GroundUp, and do not change the text. Please include a link back to the original article.