Using municipal land for bowling greens during a housing crisis is unjust

Fish Hoek has enough space to build affordable housing

The City of Cape Town wants to renew the the lease of municipal land in Fish Hoek for bowling greens. Had Ndifuna Ukwazi not objected the renewal of the lease might have gone unnoticed. We need to ask ourselves why well-located land is being disposed of so flippantly while thousands of residents remain landless and without decent housing.

Leasing of public land by the City is a mess. There are 3,500 parcels of land leased out across Cape Town and officials don’t really know where it all is and who is leasing it. Renewals are processed routinely without any consideration of what the highest and best use for the land would be, relying instead on what comes back in public comments. This is no way to manage land transformation. The facilities and asset management directorate seem to think they are exempt from the lawful obligation to advance equitable access to land and housing.

In this instance, the City is considering disposing of 7,000m² of public land to a private bowling club for less than R1,000 a year. To put that into perspective, some residents pay more every month to rent a shack without basic services. But this is a systemic problem. The bowling club in Green Point currently rents for R1,000 a year. In Somerset West last year, the City signed another 20 year lease for 20,000m² of public land for R1,600 a year for bowling greens and tennis courts.

These leases raise no rates, create few jobs, and serve a small group of people rather than the public interest. In former “Whites only” areas it is truly business as usual when it comes to public land.

The law is very clear on this. The Constitution obliges the City to use land for redistribution and redress, and the Bill of Rights obliges the City to advance the right to housing and equality. The Spatial Planning and Land Use Management Act obliges the state to advance spatial justice, desegregate racial enclaves and build a sustainable and efficient city form. Asset management law obliges the City to consider community needs (not just land value or the needs of local wealthy residents).

In fact, development of land like this is at the heart of the City’s new “Transit Oriented Development” policy. It is 500m away from the Fish Hoek train station and taxi rank and next door to retail opportunities along the Main Road. The False Bay College campus is just 200m away and Fish Hoek Primary School and High School are just 600m away. The land forms part of a larger complex known as Central Circle, which includes a public park, public clinic, public library, sub-council office, fire station, community hall and some private homes. Building homes here makes sense - dense, integrated, affordable housing close to services and opportunities.

This site would be perfect as social housing, managed rental housing for households earning R1,500 to R15,000 per month. Tenants might include care workers, domestic workers, or retail and service sector workers, or elderly residents who are unable to afford ever-increasing rentals on the open market. Much like the City’s recent affordable housing projects in Woodstock and Salt River, social housing can be built off-budget because it is financed directly by national grants, loans from banks and cross-subsidisation from market rate housing. These models only work on well-located land and we have to consider them at scale when the water crisis has stripped the City of funds and the national Human Settlements Grant has been slashed by half.

This is the only integrated affordable housing in Cape Town’s south peninsula, and it was built by the Smuts government during World War II. Photo: Kalk Bay Historical Association

The only example of integrated affordable housing in the south peninsula was built by a racist administration. The Fishermen’s Flats in Kalk Bay, built between 1941 and 1945, were a rare example of mixed race community development. The flats survived the 1967 Kalk Bay Group Areas Act through organised resistance.

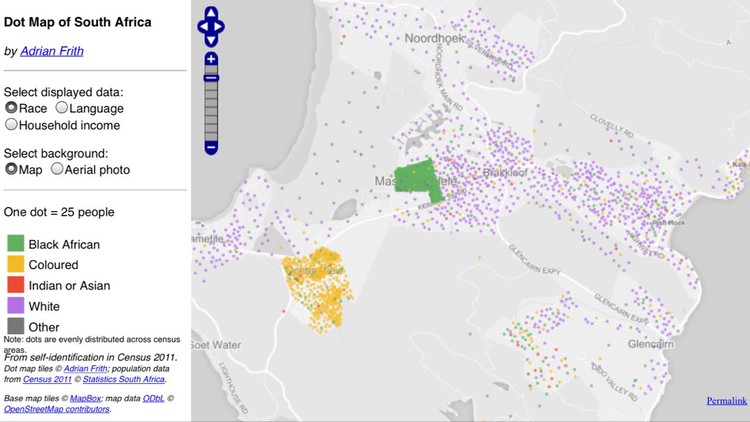

Meanwhile, the Fish Hoek valley is one of the most segregated areas in the city. Fish Hoek is 81% white, while Masiphumelele is 89% black and Ocean View is 91% coloured.

Map of households by race for Fish Hoek area based on 2011 census. Source: Adrian Frith

Our democratically elected city government is not dismantling but actually replicating apartheid spatial planning: The projects planned for the south peninsula are at Masiphumelele Phase 4, Ocean View Infill and Dido Valley. None of these disrupt segregation and the result is predictable: high density poverty traps for black and coloured residents on the periphery. Already Masiphumelele has a population density of 40,579 people per km², Ocean View is 7,734 per km² but Fish Hoek is only 883 per km². That is unjust.

So what is the solution?

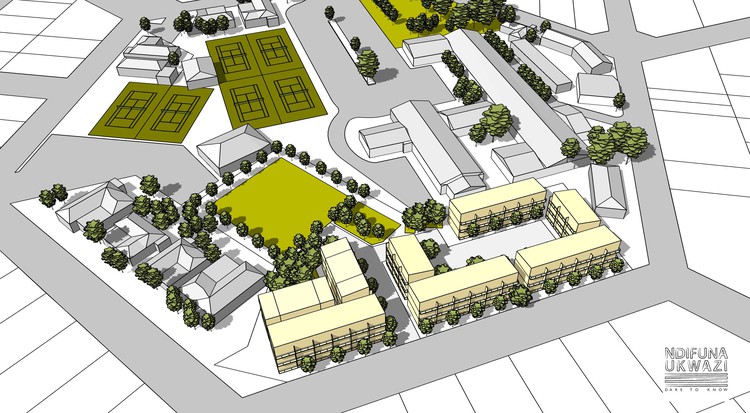

The most ambitious plan would use all the bowling greens to build three apartment blocks about three stories high around semi-private courtyards. This would yield 171 one-bedroom apartments though this could be adjusted to include more bachelor or two-bedroom homes. Some market rate housing could be included to cross-subsidise the affordable housing and ensure the development was mixed-income.

Graphic of scenario one by Ndifuna Ukwazi

An alternative plan would retain one bowling green but demolish the club house (members could meet in the Fish Hoek Community hall or the Moth hall next door). The City would be able to build 114 one-bedroom apartments on the remaining land.

Graphic of scenario two by Ndifuna Ukwazi

The alternative is another decade of urban sprawl, the replication of townships on the periphery, and the paving over of ecologically sensitive areas such as the Philippi Horticultural Area, which all result in greater inequality and more congestion on our roads as people commute from further and further away.

This bowling green is just a start. We need to review and redistribute leased public land on golf courses and parking lots across the city. What is missing is the political leadership and vision to do what is necessary.

Views expressed are not necessarily GroundUp’s.

Support independent journalism

Donate using Payfast

Don't miss out on the latest news

We respect your privacy, and promise we won't spam you.

Next: 18-year-old informal miner mourns his dead friend

Previous: What are the limits of our right to know? An apartheid-era crookery case will provide the answer

Letters

Dear Editor

How often has Groundup become a mouthpiece for Ndifuna Ukwazi and why?

If one looks at comments posted on Ndifuna's Facebook page, in relation to this article for instance, one would realize just how unpopular Ndifuna is, with their approach of attacking public open spaces and sports facilities, and handing it over to developers.

So why does Groundup effectively endorse them but publishing them so often? What is the connection? Answers please.

GroundUp Editor's Response

Dear Mark,

GroundUp mostly reports on actions by civil society organisations of which NU is one. In recent weeks, GroundUp has written several articles on ongoing actions of land occupations and calls for housing, most of which did not involve Ndifuna Ukwazi.

We believe that we have written as many articles on actions by NU as we have about social grants and the Black Sash. Please do let us know if you disagree with what is stated above. We would appreciate any suggestions from our readers.

© 2018 GroundUp.

This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

You may republish this article, so long as you credit the authors and GroundUp, and do not change the text. Please include a link back to the original article.