Minimum prison sentences must go, says Constitutional Court judge

They “are poorly-thought out, misdirected, hugely costly and an ineffective way of punishing criminals”

Constitutional Court Judge Edwin Cameron called for an end to mandatory minimum sentences. This was in the annual Dean’s Distinguished Lecture of the Law Faculty of the University of the Western Cape on 19 October. Here follows an edited and abbreviated version of his speech. (You can read the full speech which contains footnotes and references that have been omitted here. Please, before responding to this article, make sure to read the full version.)

Twenty years ago our Parliament adopted the Criminal Law Amendment Act of 1997, introducing the harsh mandatory minimum sentencing laws that have plagued our country ever since.

The statute strictly curtails the power of judges to determine the length of certain prison terms. They may only depart from the pre-determined sentences if they are satisfied that “substantial and compelling circumstances exist which justify the imposition of a lesser sentence”.

The Act mandates life sentences for certain serious offenses, including premeditated murder, murder of a law enforcement official or potential state witness and various forms of rape. For other offenses, such as robbery and certain drug related offenses, offenders must be sentenced to 15 years in prison.

Make no mistake: all the violent crimes listed are horrible and I do not argue that criminals should not suffer severe punishment for the horrors they inflict on members of the public.

My point is different. It is that minimum sentences are a poorly-thought out, misdirected, hugely costly and, above all, ineffective way of punishing criminals. They have a pernicious effect on our correctional system, the offenders in it, and, most of all, us – our society. Minimum sentences offer us a false promise – the belief that we are actually doing something about crime. And this false belief lets those who are responsible for effectively dealing with crime – our society’s leaders – off the hook.

How did we get mandatory minimum sentences?

Understanding our current mandatory minimum scheme requires us to go back to 1994. Just as our country pulled itself out of the pernicious and degrading horrors of apartheid and into democracy, there seemed to be an explosion of violent crime.

This was based in a grim reality. In the statistical year 1995-1996 alone, there were nearly 27,000 murders.

At that time, crime was seen not merely as an unfortunate reality. As President of the Constitutional Court, Justice Chaskalson wrote in S v Makwanyane, the great decision that declared the death penalty unconstitutional:

“The level of violent crime in our country has reached alarming proportions. It poses a threat to the transition to democracy, and the creation of development opportunities for all, which are primary goals of the Constitution”.

The population’s rising sense of fear after 1994 was accompanied by sharply diminishing institutional proficiency on the part of the new state. The police forces inherited by South Africa’s first post-apartheid government “were in a shambles”; they were “poorly led, poorly trained and thoroughly bewildered by the transition to democracy”. They were one-fifth smaller in 1999 than they had been in 1994 and they were worse equipped.

So Parliament felt compelled to act by creating mandatory minimum sentencing, despite the fact that South Africa had already experienced the ineffectiveness and harshness of that scheme under apartheid. Mandatory minimums for dagga crimes had an appalling impact, were known to have failed completely, and were condemned with unusual outspokenness by the apartheid judiciary—even within the context of “political” (anti-apartheid) cases.

Despite this, the 1997 statute was adopted, and it was adopted in haste. A report of the Law Reform Commission, which set out six alternatives to our current scheme, came too late for Parliament to consider it. Parliament selected the harshest option – without the benefit of mature law reform deliberative processes.

In making its selection, the government looked to the UK and the US experiences with mandatory minimums. Politically, this provided seeming benefits:

-

Harsh compulsory sentences eliminated the risk of judges supposedly being “soft on crime”.

-

They diminished the risk of inconsistent sentencing.

-

Most important, they provided politicians with a pay-off – the appearance of a state coordinated and purposeful in dealing with crime, responsive to public anxiety and fears, and tough on criminals.

The fact is that Parliament didn’t know anything, and may have been misinformed. As with our national response to AIDS we should have rigorously followed evidence and evidence-based solutions. But we didn’t. As with AIDS, this may have cost us dearly.

Instead, Parliament committed itself to the new system and it packaged it as a temporary solution to a temporary problem. Yet, the statute was extended every two years until 2007, when Parliament made only minor amendments and made the new sentences permanent. It is now two decades since the minimum sentences were enacted. They are still in effect. It is time to reconsider them.

Why we punish

The moral power to put people in prison is founded on the premise that there is some underlying theory that justifies the use of state power to punish individuals. If the mandatory minimum scheme is to be justified, it must be because it promotes some defensible purpose. Scholars often speak of four potential rationales that animate the need for incarceration: deterrence, incapacitation, rehabilitation and retribution.

Our mandatory minimum scheme cannot be satisfactorily justified by any of them.

Mandatory minimum sentences deter crime, the argument goes. Drawing from rational-choice theory, they presume that criminals assess both the severity of the punishment and the probability of getting caught before they commit a particular crime. Mandatory minimums deter by making the punishment clear and well-known to the public and by increasing the severity of punishment.

The argument is intellectually appealing. Unfortunately, it is not supported by evidence.

The experts’ consensus is universally against minimum sentences. They make “little or no significant impact” in reducing serious and violent crime, achieving consistency in sentencing, or addressing public perceptions that sentences are not sufficiently severe. According to one group of experts, “no reputable criminologist … believes that crime rates will be reduced, through deterrence, by raising the severity of sentences handed down in criminal courts.”

Besides, studies show that most active and violent offenders either don’t think that they will be caught, or don’t have any idea what punishment to expect from their crimes.

The idea that prison incapacitates criminals and that longer sentences do so for longer is a better justification. There is some force to this. But it doesn’t help us explain or justify the way our mandatory minimums work in South Africa.

This is because the “incapacitation effect” is reduced as the incarceration rate increases. Even the most lenient criminal justice systems arrest and jail the worst criminals. These people should be locked up.

But locking away large numbers of less dangerous people for long periods simply does not really help to further reduce crime. Moreover, the incapacitation rationale would be fully served by the time prisoners reach 50 or 60, the age where, statistically, they are not likely to commit such crimes again.

Indeed, there is evidence that, for some, incarceration can actually increase the incidence of crime. This is because prison affords a high-level education in the social networks of criminal activity.

Rehabilitation is a third justification for locking criminals up. In fact, our Correctional Services Act provides that the purpose of the correctional system is to contribute to maintaining a just, peaceful and safe society by “promoting the social responsibility of human development of all sentenced offenders”.

But mandatory minimum sentences work perversely against that laudable objective. An offender serving a long-term or life sentence becomes a different type of prisoner – with generally lost hopes and shorn ties of community kinship, suffering the uncertainty of indeterminate release.

The fourth reason that could justify the mandatory minimum sentences is retribution – the idea that severe sentences should be imposed upon criminals engaged in the most severe of crimes.

There is a strong emotional and historical appeal to this. It dates back to the Old Testament principle, “an eye for an eye”. Its modern variant is that a criminal offender is morally blameworthy and deserves to be punished.

The basic impulse is correct. It is rooted in moral justification and makes good human sense. It is certainly the only sound rationale for the death penalty – that someone who commits an unspeakable crime against another should die an unspeakable death, at the hands of the state, when his spinal column is broken at the end of a rope round his neck after a two-metre fall.

But that same emotion – the thirst for vengeance – leads to a terrible logic. If the crime is terrible enough, must we not visit it with a horrific enough punishment to slake our thirst for vengeance?

This impulse has been responsible for the cruellest of punishments throughout history. Why hang only, when you can hang, draw and quarter? Ultimately, nothing can slake the thirst for vengeance.

And we are left with the sombre question whether the state, that represents our aspirations to just order, should be the instrument of horrific punishment. Most societies have decided ‘No’.

Under our Constitution, retribution alone cannot be the theory upon which we base our criminal punishments.

So why then the minimum sentences?

The scheme is a product of misshapen history, the wish of our politicians to be seen to be doing something about crime, and their desire to seem tough on crime.

And so, though mandatory minimums have no proven benefit under any theory of punishment, they were enacted as a hurriedly-passed, temporary measure to respond to the fears of a freshly democratic, newly transitioning, post-apartheid society.

The law is misdirected and ineffective. But more than just being ineffective, it continues to impose an enormous economic and human toll upon our democracy.

Costs of mandatory minimum sentences

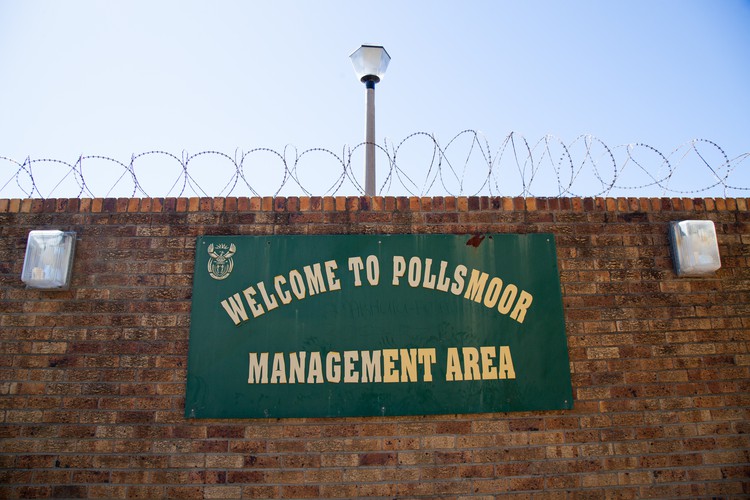

The mandatory minimum scheme overcrowds of our prisons. In 2014, South Africa’s prisons were operating at 125% of their official capacity. This was a direct result of the striking increase in long sentences.

In 1995, there were 433 people serving life sentences in South Africa. By 2016, that number had grown to 13,260.

The issue of overcrowding, perpetuated by the mandatory minimum scheme, affects all of us. It degrades our country’s respect for human and constitutional rights. It degrades our moral fabric. It degrades us.

The Constitution notes that detainees and sentenced prisoners have the right to “conditions of detention that are consistent with human dignity”. This provision requires that, at a minimum, prisoners and detainees should have access to exercise, adequate accommodation, nutrition, reading material, and medical treatment.

The Constitution also protects prisoners and detainees from cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment or punishment. Apartheid taught us the degradation of imprisonment, its unjust uses, and inhumanity. Did we learn the lesson? One might think that a country so well versed in the misuse of prisons might have, under democracy, become a leader in the humane treatment of prisoners. But the formal guarantees of our constitutional system are undermined by overcrowding

And then there is racial disparity. As a result of apartheid, our black populations were subordinated, marginalised and disenfranchised. Our mandatory-minimum system perpetuates this disparity. The development of the prison system was closely linked to the institutionalisation of racial discrimination in South Africa.

The worst effects of sentencing policy — the war on drugs, the long sentences for petty crime, and the long pre-trial prison stays — disproportionately affect the poor and Black and Coloured people.

Today, nearly 80% of our current prison population is black, 18% is Coloured and less than 2% is white. If we care about racial equality, we must acknowledge the racist aspects of our current, post-democracy penal system.

The cost of mandatory minimum sentencing scheme is exorbitant. Unduly long sentences impose a strain on our country’s economic health. With an inmate population of nearly 160,000, the annual cost of jailing offenders is R21 billion. This means that an average annual cost to house a single prisoner for one year is over R133,000. Compare this to the fact that the average cost of educating a child in a public school is less than one-quarter that amount (R32,000).

But it is easy to get lost in numbers. Long sentences take a toll on so many lives. Years and years behind bars affect not only the prisoner. Prison sentences — long prison sentences in particular — destroy families, put children at a disadvantage, and perpetuate cycles of violence and disparity.

The minimum sentencing scheme has blunted our ability to progress as a society.

We know what works to help stop crime. It is not singling out a small handful of criminals and imposing long sentences on them. It is the tough task of police follow-up, detection, pursuit, arrest, arraignment, prosecution and sentence.

For this we need to build our criminal justice systems. We need to train detectives and police personnel, improve our blood analysis and other evidence and forensic analysis systems. Instead, minimum sentences have diverted public attention.

There are no shortcuts to fixing our system of criminal justice. Addressing crime in a way that is effective and also preserves dignity and justice is difficult. It will take courage from our leaders. But it is indeed possible.

We must devote the resources to ensure that prisoners receive constitutionally adequate standards of care. And, if that is impracticable at our current level of incarceration, we must adopt strategies for reducing incarceration.

But there are several things we can do now to safely reduce the number of incarcerated. We should:

-

Scrap minimum sentences for most low-level, nonviolent, or non-serious crimes, particularly drug related offenses. More suitable punishments include: shorter sentences, probation, community service, electronic monitoring, or medical treatment.

-

Replace the mandatory minimum scheme with a Sentencing Council to develop and review sentencing guidelines. Many countries use such a mechanism, but our Parliament has yet to take it up.

-

Explore treatment for the mentally ill, instead of prison — an institution ill-equipped to treat those with mental health or addiction problems.

-

Overhaul pre-trial detention practices. Denial of bail should be based on danger to society, not on whether you can afford bail.

Right now, we have no sense of immediacy in considering these constitutional and moral challenges. This is because we are all terrified of crime — all of us. But our fears should be directed at solutions that work. Minimum sentences have done nothing for us.

Instead, let us hold our leaders accountable. Let us see minimum sentences for the false promise they were. They proved pernicious, misguided and futile. Let us replace them with redoubled commitment to detecting, arresting, arraigning, trying, sentencing and jailing every single rapist, every murderer, every sexual offender. Only by taking these steps will we make South Africa a safer, peaceful, and humane society. Only by taking these steps will we actually deter crime.

Views expressed are not necessarily GroundUp’s.

Support independent journalism

Donate using Payfast

Don't miss out on the latest news

We respect your privacy, and promise we won't spam you.

Letters

Dear Editor

Justice Cameron's proposals make total sense, and it is preposterous that there are mandatory minimum sentences for nonviolent and drug offences. It is equally preposterous that there are not mandatory minimum sentences for killing and injuring through dangerous driving - behaviour that according to the CSIR is killing around 15,000 South Africans annually, and seriously injuring another 60,000, at a cost to the economy of R150b per annum.

Mandatory minimum sentences genuinely work as a deterrent in this category of crime, because they can be taught to the motoring public through the media and the driver licensing process and because the motoring public have no substantive motives to kill and injure other people. In SA, drivers who kill multiple people under the most egregious of circumstances normally walk away with a suspended sentence and a brief, farcical "house arrest", often without even a license suspension.

In other words, our courts allow them to walk out the door and get back into their cars. The same driver in the UK would have done time based on the number of people killed and the aggravating circumstances, with additional years for speeding, drink-driving and cellphone use, with a maximum of 14 years custodial sentencing. License suspensions are mandatory and take effect only upon release from prison. SA's road death rate? 34 per 100k. The UK's? 2.7. Our current system let's down future offenders as much as it does future victims and their families.

Dear Editor

I propose any prisoner who completes a employable diploma / degree should have their time reduced by three times the study duration of the course taken.

Having over 100,000 people doing nothing all day is very frightening. Spending R133,000 on each person is sad as it's like a waste of money.

Give prisoners the possibility to educate themselves out of jail.

© 2017 GroundUp.

This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

You may republish this article, so long as you credit the authors and GroundUp, and do not change the text. Please include a link back to the original article.