Mozambique: These are the children the United States left to die

Part one: How the Trump Administration abandoned orphans with HIV

Maria (we have withheld her surname) sits in her home and holds her granddaughter Teresa. All parents and guardians gave permission to use the photos of children in this article. All people photographed understood their photos would be published in news media. Photos: Jesse Copelyn

In Mozambique, the health system is overwhelmingly built on US money. When the Trump administration instantly pulled much of this funding without warning, disease and death spread. Spotlight and GroundUp visited one of the worst affected regions to describe the human toll.

Hospitals run short of life-saving drugs. Doctors and nurses are laid off en masse. Hospital lines get longer and longer. Some patients are given the wrong medication, likely because the data capturers (who manage patient files) have lost their jobs. Community case workers who had been delivering HIV medication to orphaned children stop coming. Without their antiretrovirals (ARVs), some of these children die.

Following Donald Trump’s executive order to suspend US global aid funding on 20 January, the health system in parts of Mozambique fell into a state of chaos.

US aid agencies had financed much of the country’s healthcare workforce, along with the transportation of drugs and diagnostic tests to government hospitals.

In some provinces, this money came from the US Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), which restored much of its funding shortly after the executive order. But in the central provinces of Sofala and Manica the money came from the US Agency for International Development (USAID), which permanently pulled most of its grants.

For a week in June, I travelled to nine rural villages and towns across the two provinces. Interviews with grieving caregivers, health workers and government officials across these settlements all converged on one clear and near-universal conclusion: the funding cuts have led to the deaths of children.

One of the clearest reasons is this. After USAID-backed community health workers were dismissed, thousands of HIV-positive children under their care were abandoned.

Panic at all levels

In 2020, a Sofala-based organisation called ComuSanas received a large USAID grant to employ hundreds of community workers throughout rural parts of the province.

“The project aimed to reduce mortality among children living with HIV,” says Joaquim Issufo, a former community worker with the project. He spoke to me from a street market in the impoverished district of Buzi, where he now runs a stall selling fish. “We worked with children aged 0 to 17, especially orphans and vulnerable children.”

These children live in remote villages, far away from public amenities. Some were found living in homes without any adults. Many others live with an elderly grandparent who can barely afford to feed them.

Joaquim Issufo stands in front of his home in the Buzi district.

In the midst of poverty and isolation, the case workers, known locally as activists, functioned as a bridge between these children and the country’s hospitals. They shuttled diagnostic tests between communities and health facilities. They brought children their medicines and ensured they took the correct doses at the right times. And they accompanied them to health facilities, and helped them weave through bureaucracy.

Issufo notes that their role also extended far beyond health: they organised birth certificates, enrolled children in schools and referred them for housing. When drought and famine ripped through villages, they brought food baskets and provided nutritional education.

In the villages that I went to, children and their caregivers referred to the activists as “mother”, “father” or “sister”, and said that they were like family members.

But after USAID issued stop-work orders to ComuSanas in January, those “mothers and fathers” abruptly stopped visiting, and suddenly the region’s most desperate children were left to fend for themselves.

Issufo says that after this, there was “panic at all levels, both for us as activists and also for our beneficiaries”.

Children hospitalised and left for dead

About 80km from Issufo’s fish stall is the village of Tica, in the Nhamatanda district. Amidst homes of mud brick and thatch, a group of former ComuSanas activists sit on logs, buckets and reed mats and explain the consequences of the programme’s termination.

“[Before the USAID cuts], I was taking care of a boy because [he] lives with an elderly woman, and she had to work,” says Marta Jofulande, “I had to go to the health facility and give the child his [ARV] medication. I also helped to do things like preparing food. But with this suspension, I couldn’t go anymore.”

Marta Jofulande (centre) describes the impact of the funding cuts.

Shortly after, Jofulande was told by the child’s elderly caregiver that he had fallen ill, and was in critical care at a central hospital.

“I was the one bringing the [ARVs] to him,” says Jofulande, “As soon as the programme stopped, he no longer took the medication, and that’s when he relapsed. He is in a very critical condition and is breathing through a tube.”

“His name is Cleiton,” she adds. “He’s eight years old.”

Entrance to a health facility in Dondo.

Many other children have already perished. A 20-minute drive from Tica is the settlement of Mutua, in the Dondo district. There, activist Carlota Francisco says, “During this pause, we had cases [of children] that were really critical that ended up losing their lives.”

One of them had been a two-year-old girl under her care.

“That child depended on me,” says Francisco, who explains that she would fetch and provide the girl’s ARVs. After she stopped, she says the girl’s caregivers failed to give her the correct dosages.

The two-year-old died shortly thereafter.

Stories such as this were repeated in almost every village that we visited.

Often, children or their caregivers attempted to get the medication without the activists. But many of the hospitals were in a state of chaos because USAID-funded health workers and data capturers had been laid off. The linkage officers that knew these children and had previously assisted them were gone too.

(The procurement of the country’s ARVs is financed by The Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria. This money continues to flow, but the distribution of these drugs to hospitals relies on US money.)

Endless queues, drug shortages and the loss of patient files meant some didn’t get their medication.

Rates of ARV treatment fall throughout the province

The director of health for the Buzi district, Roque Junior Gemo, explains that a key role of the community workers had been to extend health services to remote areas that they had long struggled to reach.

“They are like our tree branches to bring services to the people,” says Gemo, “Our villages are very remote, and we have a large population that needs information [and] basic services.”

“Especially in the HIV area, we have terminal patients who were once followed up by activists. They used to get medications at home. Without that help, their condition worsened, and some died.”

This forms part of an issue that extends far beyond the district of Buzi.

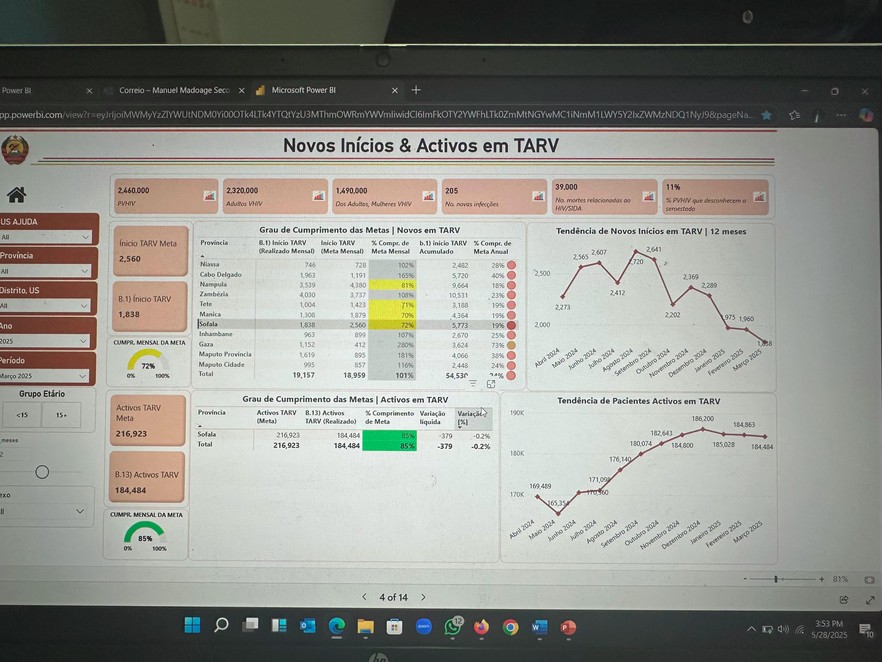

A government dashboard showing the current HIV numbers in the Sofala province. The photo is of a provincial government laptop. The bottom right panel shows the number of people who are on ARV treatment in Sofala. After steadily rising, the number begins to drop from January, when the cuts begin.

In the Sofala capital of Beira, I sat down with some of the province’s senior health officials. The HIV supervisor for the province, Manuel Seco, provided data on the HIV response in Sofala, before and after the cuts.

Between May and December of 2024, the total number of people on ARVs in the province had risen by over 20,000 people, the data shows. This increase occurred steadily, rising by 500 to 5,000 people each month.

But as soon as the cuts were made, this progress was halted and the trend reversed. Since January, the number of people on ARV treatment has been falling by hundreds of people each month.

The reason, according to Seco, is that many people who were on ARVs have stopped their treatment, while new ARV initiations have dropped sharply.

And the impact extends far beyond just the HIV response.

An ambulance parked in the grass in the Dondo district of Sofala Province.

TB left untreated

Buried within a compound owned by Tongaat Hulett is a government hospital that services the rural population of Mafambisse, in Dondo district. Joaquim Mupanguiua, who deals with TB at the hospital, says that after the activists were laid off, the hospital saw a steep decline in the number of TB patients coming to the facility.

“Only when they are already very ill do they come to the health unit,” he says. “But with the activists they would easily go to the communities and find the sick.”

Indeed the number of patients coming to the hospital is roughly a third of what it once was: “We used to get around 28 to 30 [TB] patients per month, but now we’re down to fewer than 10,” Mupanguiua notes.

Because patients come to the hospital when they’re already severely ill, there’s significantly less that health facilities can do for them. It’s thus no surprise that Mupanguiua believes that there has been an uptick in needless TB deaths.

Finding other ways

Back in the Buzi district office, Gemo says that efforts have been made to assist terminal patients that had previously been supported by activists, but there are so many people in need that they aren’t able to help everyone.

Activists often said something similar – they continue to visit their beneficiaries when they can, they say, but without ComuSanas sponsoring their transport costs, many struggle to visit children in remote areas. And the loss of their income with the programme means that they now need to spend their days finding other ways to survive – subsistence farming and street markets are the usual routes.

But this work rarely offers the kind of regular income that ComuSanas had been providing.

“Honestly, buying notebooks, pens and clothes for my children [has become] very difficult,” says Dondo-based activist, Brito Balao. Meanwhile, in Tica, activists asked how they could provide food to their former beneficiaries when they are themselves going hungry.

Despite this, the activists still live within the same villages as their beneficiaries. And so unlike those in Washington, they cannot withdraw their support without facing the resentment or desperation of their communities.

“We work with love, and we get really sad not being able to be there for those kids,” says one Mutua-based activist. “There’s even another family that cried today [when they saw me]. ‘You’ve been away for a while,’ they said. Gosh, we feel bad.”

Among former beneficiaries of the programme the sense of abandonment was palpable, and their anger was often directed at the former activists. This was often compounded by the fact that no one had explained to them why the programme had stopped.

Joana sits with her daughter.

In the village of Nharuchonga, Joana, explains that in the past her activist, Fatima, would always come and ensure that her daughter took her ARVs. Now that Fatima has stopped coming, her daughter doesn’t always take the medication, she says. (Fatima is present during this conversation.)

“We’ve been abandoned by Fatima,” she states, looking directly away from the former activist. “Until now we have been too shy to ask why she has abandoned us.”

In many other cases, the tone was simply one of sadness.

Back in Tica, inside an outdoor kitchen made of corrugated iron sheets, Maria holds her five-year-old granddaughter Teresa. Despite facing hunger at various points over recent years, she cooks sweet potatoes above a small fire, and insists that everyone eats.

Both of Teresa’s parents died of AIDS, says Maria. It has been left to her to raise the child, all the while trying to grow rice and maize for subsistence – an effort hampered by frequent drought.

For a long time Maria has had help with this parental role, she says. Activist Marta Jofulande had been assisting her family and acting like a mother to the child. But since the programme was terminated, they don’t see much of Jofulande anymore. Instead, five-year-old Teresa has been forced to deal with the exit of yet another parental figure.

Support independent journalism

Donate using Payfast

Don't miss out on the latest news

We respect your privacy, and promise we won't spam you.

Next: South Africa needs to do more to tackle antimicrobial resistance, warn experts

Previous: MPs not impressed with new SASSA verification process

© 2025 GroundUp. This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

You may republish this article, so long as you credit the authors and GroundUp, and do not change the text. Please include a link back to the original article.

We put an invisible pixel in the article so that we can count traffic to republishers. All analytics tools are solely on our servers. We do not give our logs to any third party. Logs are deleted after two weeks. We do not use any IP address identifying information except to count regional traffic. We are solely interested in counting hits, not tracking users. If you republish, please do not delete the invisible pixel.