National minimum wage part one: Comparing South Africa to other countries

Deputy President Cyril Ramaphosa is hosting a social dialogue between business, labour and other constituencies over setting a national minimum wage (NMW). Minimum wages currently vary from sector to sector. A NMW would set a national wage floor applying to all workers irrespective of existing collective agreements and sectoral wage determinations. What level should the NMW be? This is the first of a three part series by two University of Cape Town professors.

During his recent trip to South Africa, Thomas Piketty supported the introduction of a NMW if set at the ‘right’ level. What is the right level and how should we go about finding it?

The ILO’s Minimum Wage Fixing Convention (1970) recommends that policy makers consider the following when setting minimum wages:

a) the needs of workers and their families, taking into account the general level of wages in the country, the cost of living, social security benefits, and the relative living standards of other social groups;

b) economic factors, including the requirements of economic development, levels of productivity and the desirability of attaining and maintaining a high level of employment.

While the ILO leaves it up to the national stakeholders to attribute weight to these different social and economic objectives, it has tentatively suggested various ‘benchmarks’. In its 2008/9 Global Wage Report, the ILO suggested that a minimum wage of 40% of the mean (average) national wage might be a “useful reference point” given that many countries clustered around that level, but that the final value should depend on “country-specific factors”. Other suggested benchmarks include setting it at between 50 and 60% of the median wage (that is the wage at the middle of the wage distribution) or 30 to 60% of GDP per capita (average income per head).

Where inequality is high, the median wage is a better measure of the typical wage than the mean wage because very high earnings pull the average wage upwards. Where unemployment is high, GDP per capita is the more inclusive indicator (because national income is divided by the entire population, whereas mean and median wages take into account only wage earners).

How does South Africa’s minimum wages perform in relation to these benchmarks?

| Most recent data | Expressed in 2015 prices | |

| ILO estimated average minimum wage | R2,475 (2013) | R2,740 |

| National Treasury calculation of the average sector determination (weighted by employment) | R2,704 | |

| ILO mean wage estimate | R8,194 (2013) | R9,077 |

| Arden Finn estimate for the mean wage** | R8,168 | R8,544 |

| NMWRI*** estimate for mean earnings | R9,073 | |

| National Treasury estimate for the median wage* | R3,145 | |

| Arden Finn estimate for the median wage** | R3,224 (2014) | R3,372 |

| NMWRI estimate for median earnings | R3,347 | |

| ILO estimate of minimum wage to mean wage | 30% (2013) | 30% |

| National Treasury estimate of minimum wage to median wage | 85% |

Table 1. Estimates of minimum, median and mean wages in South Africa.

Sources: http://www.ilo.org/ilostat; MacLeod (2015): Measuring the impact of a National Minimum Wage, National Treasury;

Finn (2015: 42) A National Minimum Wage in the Context of the South African Labour Market;

National Minimum Wage Research Initiative: Presentation of Research Programme (NMWRI) (2015) presented by G. Isaacs at NEDLAC.

* estimated from MacLeod (2015);

** outliers and zero-earners removed.

*** NMWRI is the National Minimum Wage Research Initiative.

Minimum wages are currently set in South Africa at different levels for different economic sectors and regions, either through collective bargaining (in bargaining councils, and then “extended” across the entire sector by the Minister of Labour) or through sectoral determinations by the Employment Conditions Commission (ECC).

The lowest bargained wage is R989 per month, in the road freight sector (MacLeod, 2015) and the lowest ECC sectoral determination in 2015 is that for domestic workers in non-metro areas (R1,812 per month). South Africa’s (employment-weighted) average minimum wage is estimated by various analysts to be about R2,700 in 2015 (see Table 1).

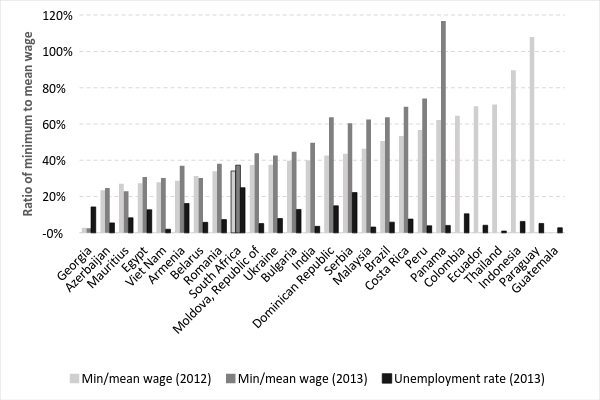

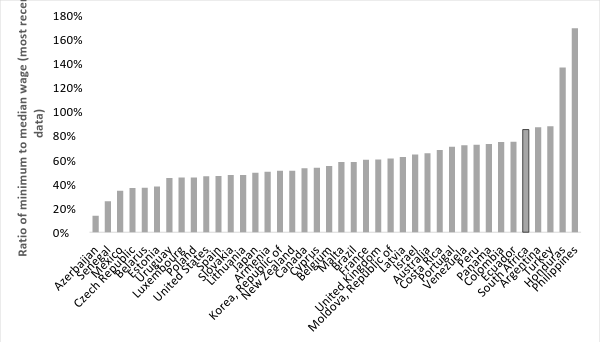

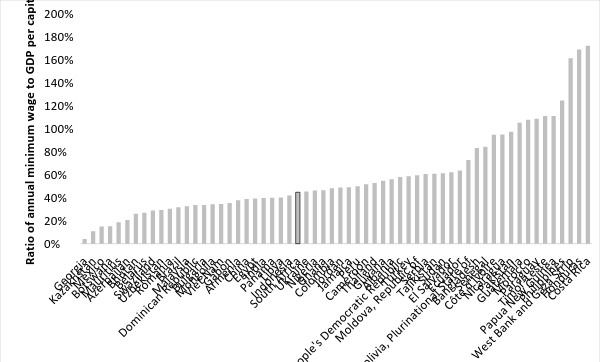

Figures 1, 2 and 3 report middle-income country performance with regard to the three proposed international benchmarks. They show that South Africa’s average ratio of minimum to mean wage is below (but not significantly so) the 40% benchmark, that its ratio of minimum wage to median wage is well above the 50 to 60% benchmark and that its ratio of (annual) minimum wage to GDP per capita is comfortably within the 30 to 60% range and is higher than that of Brazil.

Figure 1. Unemployment rate and the ratio of minimum wages to mean monthly wages in middle-income countries.

Figure 1. Unemployment rate and the ratio of minimum wages to mean monthly wages in middle-income countries.Source: ILOSTAT: http://www.ilo.org/ilostat

Figure 2. Ratio of minimum wages to median monthly wages (all countries)

Figure 2. Ratio of minimum wages to median monthly wages (all countries)Source: ILOSTAT (http://www.ilo.org/ilostat), Table 1.

Figure 3. Ratio of (annual) minimum wages to GDP per capita (2013) for middle-income countries.

Figure 3. Ratio of (annual) minimum wages to GDP per capita (2013) for middle-income countries.Source: ILOSTAT (http://www.ilo.org/ilostat), World Development Indicators.

This suggests that a minimum wage of about R2,700 is broadly in line with international benchmarks.

Yet setting a NMW with reference only to international “benchmarks” would fail to account for country-specific factors. As emphasised by the ILO, other factors to be considered include social assistance and the level of unemployment. South Africa has a very high rate of unemployment (see Figure 1), very limited social assistance for the unemployed and hence job creation is an urgent priority. There are thus good reasons for prioritising employment creation, even if this means setting a relatively low NMW and continuing to allow the ECC to make higher minimum wage determinations, where feasible, on a sectoral basis. We pick these issues up in parts 2 and 3.

Part two: what will happen to jobs?.

See also:

-

Poverty report strengthens COSATU’s case for national minimum wage and comprehensive social security

-

Minimum wage debate: the old cheap labour system will get us nowhere

Views expressed are not necessarily GroundUp’s.

Support independent journalism

Donate using Payfast

Don't miss out on the latest news

We respect your privacy, and promise we won't spam you.

Next: Site C Khayelitsha

© 2016 GroundUp.

This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.