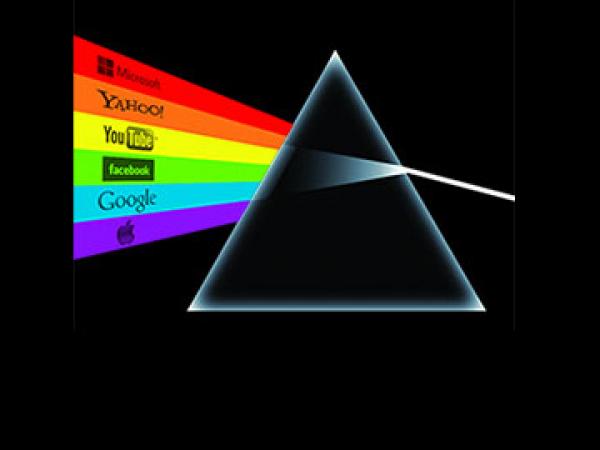

The Opaque Prism Part Three: How can we make our online lives more secure?

This is the last in a three-part series on the United States government’s PRISM programme.

Also see Part One Some Internet users aren’t American and Part Two: What’s wrong with PRISM?

There are things we can all do. Collectively we can take political action. Consider signing the Avaaz petition (albeit that it should have been better worded and less overreaching). Write to the companies whose services you use asking them if they are sticking to their privacy agreements with you in light of the PRISM leaks. Take part in demonstrations at US embassies and consulates that demand to know more about PRISM.

Unfortunately taking action to make sure that no unauthorised person can read your emails or view your online documents and photos is inconvenient and exceeds the technical knowledge most users have the time to acquire. Besides, even experts on computer security make mistakes and leave their data insecure.

I have always considered the advice of computer security experts a bit paranoid and over-the-top. After PRISM, I am not so sure. Despite occasionally teaching computer science I am not an expert on computer security, so with some trepidation here are a few suggestions. Some are easy to do and others hard. Even doing just one of these will make your data a bit more secure than before. At the same time, there is no point in being paranoid; protect what truly needs to be secure.

Learn how to encrypt your emails. It’s a little inconvenient and perhaps you probably don’t need to encrypt all your emails. Unfortunately, for email encryption to be useful, the people you email need to co-operate too. Also, use proper passwords. One of my friends used password1 as his Gmail account password. Google cannot be blamed if the NSA or anyone else read his emails.

Don’t write or upload anything to Facebook, any website or social media platform, that you aren’t comfortable with anyone anywhere in the world seeing now or anytime in the future of humankind. Use programs like Skype or Google Talk with caution. Always log out of Facebook when you are finished using it. When you remain logged in and browse to another site, that site might be one of Facebook’s many partner sites that sends tracking information back to Facebook. Facebook uses this information to send you tailored adverts, but there are obvious privacy implications. You can install a plugin for Chrome or Firefox called Facebook Disconnect which prevents your information being sent to Facebook from the sites you browse.

If you use Firefox or Chrome, consider installing the HTTPS Everywhere plugin from the EFF. It encrypts your communication with many major websites, preventing eavesdroppers from intercepting meaningful data.

Switch to GNU/Linux on your PC or laptop. Seriously. I have been imploring my friends for years to do this, often tongue-in-cheek and despite humorous derision in response. Admittedly this was once a crazy thing to ask of non-technical users. But it isn’t any longer. The modern Linux distributions are easy-to-use and compatible with a huge amount of hardware. The advantages are considerable. Viruses are extremely rare on Linux. You can use many high-quality free software programmes and you can be sure Microsoft isn’t sharing your details with the NSA. Mint, Ubuntu and Mageia are three easy-to-use popular Linux distributions. Any of these and many others will do. LibreOffice and OpenOffice are decent alternatives to Microsoft Office that offer everything a regular user needs. If you truly need Microsoft Office, perhaps because people insist on sending you complex Microsoft Office documents that LibreOffice and OpenOffice don’t display nicely, you can use a program called Wine to run it successfully under Linux.

Become less dependent on Google and Dropbox, especially if you are a political activist in a despotic US ally. This is very hard for those of us who have immersed our online lives with these companies. If you use Dropbox, consider encrypting your files. Dropbox adds its own encryption to your files, but it can un-encrypt them too and will likely do so if faced with a court order. But by encrypting your files yourself, you might be able to stop any unauthorised person, no matter how determined, from seeing your data. Encrypting your files isn’t difficult, but don’t forget your password because I doubt the NSA will spare the immense computing power needed to help you discover it! An alternative to Dropbox is Bitcasa. I haven’t tried it but I am told it works by encrypting your files on your computer before they are saved on Bitcasa’s servers, so even if Bitcasa is served with secret court orders, they probably cannot decrypt your files.

Learn how to browse using TOR (especially if you are a political activist in a despotic US ally). TOR is an open source service, ironically funded originally by the US government, that helps you “protect your privacy” and “defend yourself against network surveillance and traffic analysis.” But a reviewer of this article warns, “If used incorrectly, it can actually make people more vulnerable to attack than without it. It works by routing your traffic through a series of random, encrypted tunnels all over the world, jumping from server to server, each node completely oblivious to the traffic it’s relaying, or who it’s from. Eventually the data finally emerges unencrypted from the last server in the chain, called the TOR exit node, before it goes to the website you wanted to access. That way neither the website, not any intermediate node knows who the traffic originated from. There are two problems with this. The first is that people often assume TOR is inherently secure and send sensitive information over it, but the data is only anonymous, not end-to-end encrypted so the content itself is open for anyone to see. It should always be combined with … encryption to be effective. Secondly, there are relatively few TOR exit nodes in the world, and they are all publicly known. People who use TOR tend to be those who want to hide something, so these TOR exit notes are intensely monitored by belligerent hackers and presumably the NSA alike. Some believe that if you want to guarantee that your data will be poked at, send it over the TOR network. It’s also unbearably slow.”

Install an open source distribution on your cell phone if possible, for example Cyanongenmod on Android phones. Sadly this is not something everyday users can do, nor is it close to a guarantee against intrusion. An intelligence service can still get hold of your phone meta-data, or even listen to your calls. But at least Samsung, HTC, LG, RIM, Google or Apple won’t be getting your private data without you knowing.

Finally, a new organisation is needed. It should be a co-operative IT company whose members pay an annual fee. All members should have voting rights on big decisions. The services provided should include storage space, access to an email programme and calendar as well as file-sharing and backup and perhaps online spreadsheets and word processing. In other words it should be an alternative to Gmail, Google Docs, Yahoo!, Hotmail and Dropbox. It should not be based in the US, but in a country with very strong privacy protection and a government that is unlikely to overreach. All software on this company’s servers should be open-source and declared, but all user data should by default be encrypted so that only users themselves can decrypt it. I hope some young idealistic entrepreneurs somewhere in the world will take up the challenge to start this. Perhaps such a company already exists?

Thanks to Graham Richter for useful comments. I take sole responsibility for errors and opinions.

Also see Part One Some Internet users aren’t American and Part Two: What’s wrong with PRISM?

Geffen is the editor of GroundUp. You can follow him on Twitter @nathangeffen.

Support independent journalism

Donate using Payfast

Don't miss out on the latest news

We respect your privacy, and promise we won't spam you.

This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.