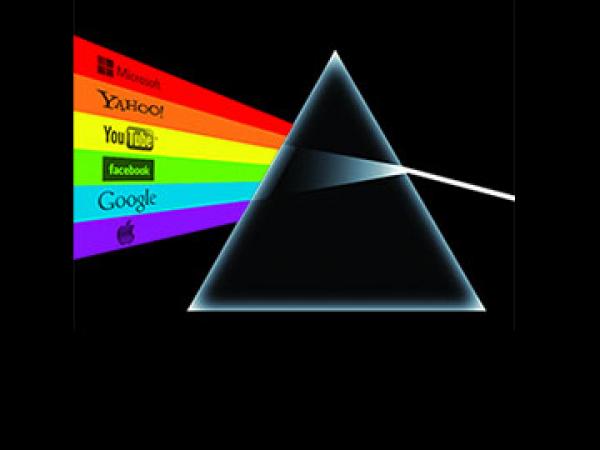

The Opaque Prism Part Two: What’s wrong with PRISM?

This is the second in a three-part series on the United States government’s PRISM programme.

Also see Part One: Some Internet users aren’t American and Part Three: How can we make our online lives more secure?

So what if the US government monitors your telephone usage, collects your emails and downloads your online documents? If you’ve got nothing to hide then what’s there to be afraid of?

Quite a few thoughtful people have asked these questions. I asked them too before I knew about PRISM. They are reasonable questions in need of reasonable answers. The answers depend on whether we are facing the best or worst case scenarios described by the EFF (see part one). In the latter scenarios there is much to be concerned about.

First, even if you trust the US government of today (I don’t), you cannot know what the US government of tomorrow will be like. In the EFF’s worst case scenarios the US government has given itself new powers. A contributor to the tech website Slashdot articulated this succinctly:

… nobody has seriously challenged the basic truth of Snowden’s leak: many of the world’s leading telecommunications and technology firms are regularly divulging information about their users’ activities and communications to law enforcement and intelligence agencies based on warrantless requests and court reviews that are hidden from public scrutiny. It hasn’t always been so.

Second, some people, who are law-abiding, value their privacy for its own sake. They haven’t given permission to the NSA to access their data. If you do not mind your electronic life being an open book, that is fine. Nevertheless, the privacy concerns of people who do not feel the same way as you should be respected.

Third, have you ever sent an intemperate email you regretted? Have you merely drafted an intemperate email but not sent it (on Gmail, drafts are automatically saved to Google’s servers)? Have you had a sexually explicit discussion with a loved one, or perhaps just a casual acquaintance, or perhaps with someone your partner did not know about? Have you downloaded copyrighted material and discussed it on email, or saved it on Google Drive? Or maybe you’ve described a recreational drug experience? Maybe you’ve written and sent very bad poetry to a friend? Or confided to your best friend something illegal you did while you were young, or not so young? Perhaps you privately wrote that you wished illness or even death upon someone? Maybe you’ve said things on Skype calls you’d rather be forgotten? If you, your children or loved ones have to answer yes to even one of these questions, then are you sure you are comfortable with your or their electronic lives being in the hands of anonymous securocrats in a dodgy US or other spy agency?

Fourth, is the threat to be most afraid of. The US government has allies across the world that suppress political organising: Turkey and the Kurds, Israel and the Palestinians, Pakistan and those opposed to its military, the UAE and all its non-citizens (i.e. most of its population), Saudi Arabia and 50% of its citizens (women), Bahrain and its Shia majority. And many more. There are elements in the US government who cannot be trusted, who will not refrain—given the opportunity—from assisting the suppression of dissent in allied countries.

What some hawks in the US government consider terrorist activity, the rest of us would consider mundane political activity. It’s plausible that the NSA would give information to the Israeli security services about youths on the West Bank using Gmail to organise a political meeting. And they’d be pounced on.

No competent terrorist would use un-encrypted emails to plan a bombing, but young people all over the world use un-encrypted emails, including Google, Hotmail and Yahoo to organise politically; they should be able to do so without fear of being betrayed to their governments by the NSA, irrespective of whether their political views repulse some in the US government.

Fifth, is that the NSA could selectively leak embarrassing private information, such as marital affairs, proof of telephone calls to sex workers (just using meta-data obtained from companies like Verizon) or other compromising information about out-of-favour politicians from foreign countries, destroying their reputations and careers. While unlikely, it is not clear that there are enough checks and balances to prevent this.

Sixth, is that the NSA could obtain confidential corporate information of competitors to American firms and misuse it. In my first draft of this article, I wrote that this is unlikely. But I am not so sure after the Guardian released Snowden’s latest revelation on the weekend that the British government spied on its allies at the G20 meeting it hosted in 2009. Other than getting an advantage in trade negotiations, what other purpose could there have been?

Seventh, intrusive and flat-out illegal online behaviour by governments is becoming far too common. Israel and the US are believed to be behind the Stuxnet worm that wreaked havoc on Iranian nuclear facilities. Iran has claimed it brought down 370 Israeli websites over insults to Islam (I do not know if this is a grandiose claim or true). The Chinese government is suspected of cyber espionage on a grand scale including interfering with Gmail accounts. A US Defence document states:

In 2012, numerous computer systems around the world, including those owned by the U.S. government, continued to be targeted for intrusions, some of which appear to be attributable directly to the Chinese government and military.

The US government has been trying to convince or shame the Chinese government to behave on the Internet. President Obama raised the problem in his recent meeting with President Xi Jingpin. With the PRISM leak, the US government has lost moral authority on this issue; Xi Jingpin must be smiling broadly. Spy agencies across the world can now feel emboldened to be more intrusive.

The argument advanced by defenders of PRISM is that it stops terror attacks. But this is an amorphous claim. Unless concrete examples are given, it is an argument that is impossible to engage with, other than to say “prove it.” On the other hand, there is evidence of abuse using the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act.

Modern democracies have developed fair ways of obtaining information on suspects. Usually this is a warrant that names a specific person. Warrants are almost always time-limited with strict conditions on what information can be obtained and used. It is a mechanism that works effectively.

There will always be terror attacks and even occasionally mass homicides in western countries. Terror is not a post-2001 phenomenon either; for decades terror groups have operated across Europe and the US. As awful as they are, terror attacks are not a significant cause of death or injury. Homicide rates in western countries are extremely low. And only a tiny fraction of homicides are due to terror. Western countries have got to such fortunate positions despite—or perhaps because of—giving citizens more freedom than ever before. The new infringements on freedom and privacy that have been introduced in the US since 2001 are not a proportional response to terror and cannot be justified.

In any case the US government might do a lot more to prevent terror through other means, such as having a consistent, human-rights based foreign policy and not pissing off millions of people by invading their privacy.

Also see Part One: Some Internet users aren’t American and Part Three: How can we make our online lives more secure?

Geffen is the editor of GroundUp. You can follow him on Twitter @nathangeffen.

Support independent journalism

Donate using Payfast

Don't miss out on the latest news

We respect your privacy, and promise we won't spam you.

Next: Immigrant businessman launches a gospel album

Previous: The Opaque Prism Part One: Some Internet users aren’t American

This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.