Over 50,000 immigrants deported in 2010

A document called “Perils and Pitfalls – Migrants and Deportations in South Africa,” recently released by People Against Suffering and Oppression, explains how the rights of refugees, children and black South Africans are infringed and abused.

The report paints a picture of mass deportations. For example, in 2010, the Department of Home Affairs (DHA) reported over 55,000 deportations. Between October and December 2011 the Beitbridge Border deported over 7,500 deportees, while more than 7,000 Zimbabweans were deported between January and March 2012.

According to People Against Suffering and Oppression (PASSOP), the Refugees Act does not require asylum seekers and refugees to be detained. Immigration officers must use their discretion to decide whether or not to detain someone, and because of the harmful effects of detention, officers must favour liberty. But the report shows that, contrary to this, officers’ favour imprisonment.

The report also explains how Black South Africans who look “foreign” must carry their identity documents with them at all times to avoid arrest and detention. Jaidudien Sablay, a legal South African citizen, was questioned and harassed by South African immigration officials. “Sablay, a student at the University of Western Cape, was stopped by an immigration official and demanded he show proof of citizenship. Despite having his University of Western Cape identification card and his father leaving to retrieve the proper documents, Sablay was forcibly placed in the police van, verbally abused and threatened. Sablay’s traumatizing experience reflects the dangerous racial profiling tendencies of immigration officials,” says the report.

The report says that children’s rights are often abused. Foreign children who are not with their parent are required by South African law to be given the same rights as South African children, including access to education, health care and safety. It is illegal to detain a child who is without their parents and legal deportation can only be performed if social workers are able to make contact with their families. Yet, the report says, the children are regularly detained and deported.

PASSOP interviewed eight children who had been deported up to four times despite not yet turning eighteen years old. All the children said they had been beaten before being deported and some still had the wounds and scars. Between January and May this year, two hundred and seventy children were deported.

The report says that the Musina detention centre was shut down because of its poor conditions, leaving suspected illegal immigrants to wait for deportation in Musina police cells. The report gives examples of overcrowding, such as 17 women being kept in an 8 person cell and 55 men held in a 12-person cell. IRIN News reported having witnessed 102 men in two cells. The report also tells of detainees being held longer than the 120 day maximum allowed. PASSOP also claims that detainees do not get proper medical attention. Most detainees said that PASSOP spoke to said could not get their medicines, including AIDS medicines.

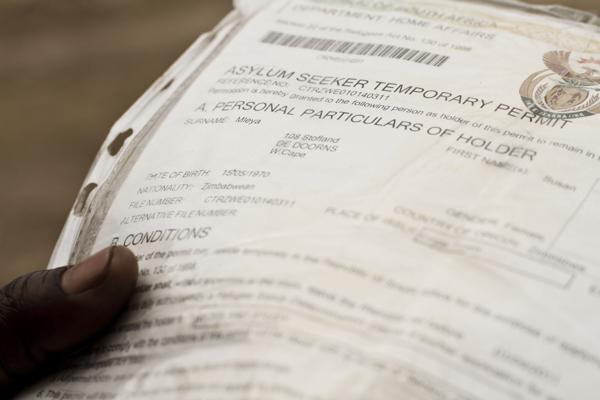

The report contains harrowing stories. Raymond, a twenty-nine years old Zimbabwean, came to South Africa in 2006. He says, “I started living in Yeoville, on the street, in the parks. From there, I got work. I started renting, up to the time of xenophobia. I was attacked during that time by the police, the South African police. They caught me and they beat me. You see the scars on my face?…They nearly killed me… They drove me to the bush area, where they wanted to dump me… They knew I was vulnerable, you see. I had to use my tactics to survive. I jumped on top of the van, and they drove all the way from that bush to Yeoville where they beat me. The policeman stepped on me with his shoe. I felt a very big pain, and they nearly killed me at that point. They took me to the hospital where I was given stitches. From there, I went to open a case about the incident, but they did nothing… They robbed me and took my money, and passport, and my jacket, which I was wearing… I was going back to follow up with my case. They saw me and said, ‘You are going to suffer for what you are trying to do, to arrest a policeman.’ I told them ‘No, I just want my passport. If you give me my passport it will be okay, I will not come back again.’ They wanted to kill me because I was following that case. They arrested me again in the morning… I don’t know what they are doing with my passport… I need my passport, you know. At the moment I have valid asylum papers, it will expire in September.”

Neither the police nor Home Affairs responded to GroundUp’s questions by the time of publication.

Support independent journalism

Donate using Payfast

Don't miss out on the latest news

We respect your privacy, and promise we won't spam you.

Next: Street lights out on Lansdowne Road for years

Previous: The Role of White Youth in South Africa’s Struggle Movements

This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.