The rabbi, the president and the Palestinians

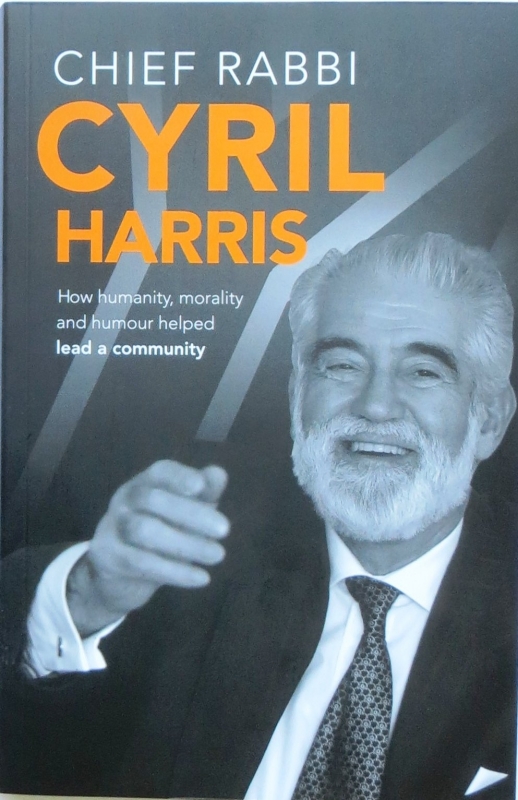

On 23 November, Geoff Sifrin’s book Chief Rabbi Cyril Harris – How humanity, morality and humour helped lead a community was launched at the Great Synagogue in Johannesburg. Judge Edwin Cameron delivered this speech. He addressed Harris’s commitment to reaching out across the divides in the South African Jewish community as well as perhaps the most vexing question facing many Jews: the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

It is a great honour for me to be here tonight. Our purpose is not just to honour the memory of a man who died prematurely almost ten years ago. It is to consolidate his memory through the practical deed of contributing to his foundation.

While we look back this evening in reflecting on the meaning of Chief Rabbi Cyril Harris’s life, we also look forward to how that life will continue to have impact in practical ways that improve people’s lives.

I must thank the Chief Rabbi’s widow, Mrs Ann Harris, for inviting me personally to be here. The book whose launch we are celebrating contains relatively little of her.

It is true that it speaks of her founding energy in creating the African Jewish Congress (AJC). It also speaks of her role in Afrika Tikkun and the Union of Jewish Women.

And yet I wonder if the book does justice in fully recognising the role that Ann Harris played in the life and career and impact of her husband.

For Ann is herself a person of formidable skills, strong personality and redoubtable courage.

When she and her spouse came to South Africa in 1988 it was for him to assume the post of Chief Rabbi. To do that, she had to leave a thriving practice as a tax lawyer in a major London law firm.

She immediately set about making her influence felt here. Although the book could have contained much more about her role, the power of her personality nevertheless comes through.

Listen to her speaking about Jewish communities in Australia, USA and the English language world: “They could run a lot better than they do. There is colossal inefficiency, and jockeying for power – it’s the same everywhere. Everyone wants to be the boss. Volunteerism is run poorly – you get a few people who are really good volunteers while the rest pay lip service. Jewish communities could do better” (pp 113 – 114).

It was as this person that I met Ann Harris – a bold speaking, no-nonsense, practical-minded and immensely competent lawyer.

She was with the Wits law clinic for ten years and ran it for the last three.

She is the only person who ever sacked me from a job.

It was at her invitation that one year I undertook the job of external examiner for the Practical Legal Studies course. I did the best I could – but I must admit that I was distracted by the demands of a desperately busy human rights practice. I was not asked to repeat the task a year later. When I inquired of Ann, she said something both crisp and blunt to the effect of needing someone who was not as busy.

It was an appropriately humbling experience to be tested by Ann Harris – and to be found wanting.

The Harrises are rightly described in the book as the “royal couple” of South African Jewry. And she – a forceful and resplendent queen.

What does one say of Chief Rabbi Cyril Harris? It is remarked in the book that he was the right man for the right time. This is no doubt true. But to see it that way understates the measure of what he actively contributed to this country at a tempestuous and perilous time.

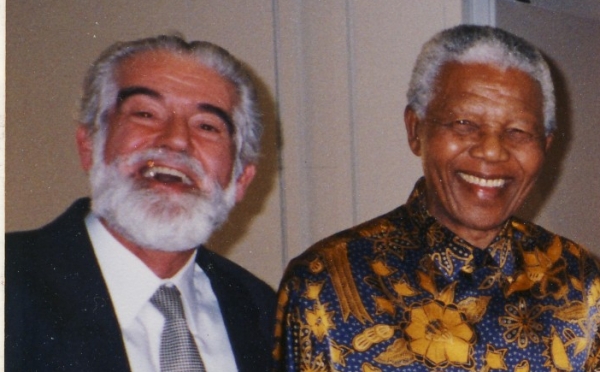

The book reveals him as commanding presence. At his funeral in Jerusalem he was called a “prophet”. He was known as “comrade Rabbi”. And to the world’s press he was “Mandela’s Rabbi”.

He emerges from the pages as an open-spirited, large-hearted human being, with a rare gift for oratory and for human engagement.

The book is candid in mentioning also his human frailties and foibles.

Indeed, it is his own wife whom we hear advising him against suing an English journalist for defamation for describing him as “a salesman in the way he promoted Jewish traditions and values.”

A salesman! He was deeply offended.

But it is Ann Harris herself who notes, “the truth is that Cyril was a quasi-salesman – his passion for Judaism made him want to pass it on to everyone whose life he touched “ (pp 231-232).

But it is to Rabbi Cyril Harris’s inescapable connection to the presidency of Nelson Mandela that I must return.

In the public mind, he will forever be associated with almost stealing the show at Mandela’s inauguration in 1994, with his magnificent oratory of passages from the Book of Isaiah.

He chose the passages to illustrate what he believed to be the values of the transition to Mandela, and those of his shepherding of the Jewish tradition in South Africa.

These were principles of justice, righteousness, peace and confidence in the future.

The book relates candidly how Cyril Harris’s political commitments and involvement contrasted sharply with those of his predecessor, Rabbi Casper (pp 16-17).

He gained a previously unthinkable political prominence and influence. This required risk-taking and courage.

He attended a funeral of a prominent Jewish activist for justice, Holocaust survivor Franz Auberbach – even though it was a reform ceremony.

He spoke at the funeral of Joe Slovo – even though Slovo reviled the tenets of Jewish religious orthodoxy.

Far from staying away, Rabbi Cyril Harris attended the funeral specifically to laud what he called Slovo’s championship of the oppressed.

The book calls him the “Tutu of South African Jewry” (p 43). But Harris went further than only the easily and mutually flattering comparison with Tutu. He ridiculed those who accused Archbishop Tutu of being anti-Semitic because of his passionate criticism of Israel.

“Stuff and nonsense” he said (p 129).

His was a generous, large-spirited, outward-looking approach that demanded respect for his religion by showing it to others.

He went before the Truth and Reconciliation Commission and apologised for “the evil of indifference which so many in the Jewish community professed” during apartheid.

“We confess that sin today before this commission”, he said, “and we ask forgiveness for it”.

This truly was a man of capacious moral vision and energies.

He died in September 2005, before his time. Mandela died 8 years later, having lived into frailty, some would say, almost beyond his time.

What do their lives say for us in South Africa today?

They call us to the three great gifts of humane leadership.

The first is to have vision even when visibility is impaired or even seen as non-existent. The leader looks beyond and guides towards the light.

The second is to offer our foes what they do not offer us in return – dignity and justice.

And third, leadership calls us to offer an encompassing and inclusive vision of our own and others’ humanity.

Isaiah 58, which Chief Rabbi Harris quoted at the presidential inauguration, makes a poignant call to “lose the chains of injustice … [and] do away with the yoke of oppression.”

This must have meaning in that most anguishing of moral questions, that most searing of human conflicts, that most irresoluble of competing histories – the Israeli / Palestinian conflict.

I do not presume to know the answers to that conflict, nor do I offer any now.

The book says that many supporters of Israel regarded President Mandela’s views on Palestine as “naïve”.

I can speak only as a lawyer, for in law we must seek what justice there is to be had in a cruel, arbitrary and often capricious world.

But if we abandon the law, we abandon all defence against the arbitrary, the cruel and the capricious.

In seeking justice for oneself and for one’s own one cannot set aside the claims of law.

What I will now say will, I know, cut to the quick of the emotions of many people present here this evening. I know that for I have experienced how friends, even close friends with friends and family in Israel, regard any criticism of it as a betrayal not just of Israel’s right to exist but of our very friendship.

It is in this way that a disjunct has opened between defenders of Israel and even its moderate critics.

A moderate and liberal-minded international human rights lawyer like Professor John Dugard has come to be seen as a pariah in many circles that abhor any criticism of Israel.

Dugard has become a pariah because he espouses the mundane and everyday doctrines of international law.

These are that –

Where it trenches on Palestinian territory, the separation barrier violates international laws;

The annexation of east Jerusalem is illegal;

Settlements on occupied Palestinian territory violates every precept of the law of nations and cannot be condoned.

Dugard was and is a mentor of mine. I admire his calm understatement and his passion for reason and logic in the law.

But he joined an even greater mentor and important figure in my life, Arthur Chaskalson, the first Chief Justice in the Constitutional Court.

Chaskalson was severely critical of Israel’s violations of humanitarian law in Gaza and the West Bank.

Chief Rabbi Cyril Harris emphasised the importance of the two-state solution. That for him entailed a Palestinian state.

One is driven to ask whether the two-state solution remains viable.

These are hard things to say on a hallowed occasion and on hallowed property.

But I say them because the moral stature of Cyril Harris and his ineradicable link with the giant moral figure of Nelson Mandela demand it.

A just resolution in Israel / Palestine is one of the pre-eminent moral challenges not just for those who support Israel but for the world at large.

We must live together in this world – with all of its caprice and hatred and cruel unpredictability. And our claims of it for ourselves must not contribute to its caprice and hatred and unpredictability.

In Long Walk to Freedom, Nelson Mandela called apartheid a “monolithic system that was diabolical in its details, inescapable in its reach and overwhelming in its power.”

Yet all of that cruel system’s reach and method and power did not save it.

It was the moral stature of Mandela and his like that overcame it.

In this uncertain world we must hope for many more of his and Cyril Harris’s kind.

Front cover of Geoff Sifrin’s new book on Chief Rabbi Cyril Harris.

Views expressed are not necessarily GroundUp’s.

Support independent journalism

Donate using Payfast

Don't miss out on the latest news

We respect your privacy, and promise we won't spam you.

Next: Audit finds serious problems at Wolwerivier. But will City listen?

Previous: Site C Khayelitsha

This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.