Report details “state of crisis” in schools for visually impaired children

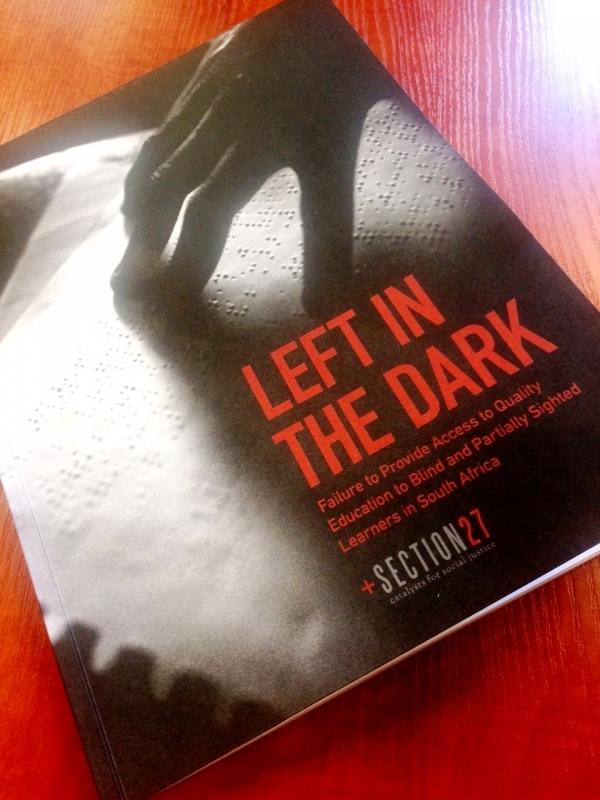

Schools for the visually impaired are in such a “state of crisis” that their students suffer “fundamental impairment of their human dignity”. This is according to SECTION27’s Left in the Dark report, which was released today, detailing extensive research into the conditions in 22 schools for the visually impaired.

The report paints a bleak picture of what SECTION27 believes amount to “constitutional violations” – from teachers who cannot read Braille and a scarcity of textbooks written in Braille to school facilities that are difficult and even dangerous to navigate as a visually impaired student.

Left in the Dark comes fourteen years after the Department of Basic Education (DBE) released their White Paper 6 on special needs education, a paper that has never been promulgated into an act. This means that it is not legally binding and thus is implemented in a sporadic manner, if at all. One of the recommendations of the report is for the legality of the white paper to be clarified and another is for an audit to be done on visually impaired schools by the DBE, which will assist in the implementation and creation of policy for these students.

Many children with disabilities do not attend school – the DBE estimates the number at 597,593 – but estimates vary. A large number of these children are those with visual impairments. The report found that there are a number of factors that lead to non-attendance including: parents fearing for their children’s safety, fees related to attending school, schools being located far from home and parents’ lack of knowledge about the capacity of their children to be educated.

Silomo Khumalo, a researcher at SECTION27 who co-authored the report with Tim Fish-Hodgson, is visually impaired himself. He says schools are very often far from a child’s home, meaning that the child who has been almost completely dependent on their parents up until they attend school, then needs to stay in boarding school.

“Parents having to separate with their vulnerable children, is a problem,” says Khumalo. There are also often reports of abuse and negligence in schools for disabled children, adding to parents’ fears.

Many parents in rural communities live off social grants and are therefore unable to afford the school fees and related costs, such as transport and hostel accommodation, leading to children not being sent to school at all, says Khumalo.

The costs of educating a visually impaired student are different from a student in a regular school due to the necessity of specialised assistive devices and resources, as well as support staff. The provision of both of these in schools for the visually impaired is another recommendation of the report.

Eugene Matshwane, a visually impaired teacher at Bartimea school in the Free State and the chairperson of the Visually Impaired Educators Forum, says that the subsidy provided to schools is not sufficient to cover the additional costs that schools, such as the one he works in, incur.

Fish-Hodgson explains that the exemption form that parents who cannot pay fees need to fill in is complicated. As a result it is often not completed and the no-fees school is not compensated for the non-fee paying students.

One of the requirements of White Paper 6 is a conditional grant from the national government to cover non-personnel funding. The grant has yet to be established, with the report stating “at times it appears that no effort has been made to fulfil the requirements of White Paper 6 at all”. The report also recommends that the grant be immediately implemented and should eliminate school fees for public special schools.

Inadequate training of educators as well as inadequate provisioning of both educators and support staff are key issues in the report. The report recommends that training in Braille for educators should be available on a yearly basis and that provision is made for both educator and non-educator positions at schools.

Matshwane says in some cases there are children with visual impairments and other children with hearing impairments in the same school and sometimes even in the same class. It is difficult for a teacher to be specialised enough in both to communicate in sign language and adequately explain visual concepts to a visually impaired learner.

Grouping students with different disabilities into one school leads to what the report calls “two completely separate schools on a single premises with a single schools’ budget and staff complement”.

The report highlights that most educators arrive at a school for the visually impaired without any knowledge of Braille and there is no professional educators’ qualification that is focussed on teaching visually impaired students. Nor is there a detailed or routinely implemented policy on training educators in Braille.

“The teachers need to know Braille… they must learn to read and write Braille so that they can mark our work,” says Oswold Feris in the report, a grade 12 learner at Retlameleng in the Northern Cape. “They often ask other teachers who might not have the knowledge of the subject and they mark us down.”

Hlulani Malungani in grade 11 at Rivoni School for the Blind in Limpopo, says in the report: “I also learnt Braille, being taught by other learners [at my school]. Teachers cannot read contracted Braille at all.”

“I wanted to do maths,” says Khumalo, “but we never had a teacher who could teach us maths using Braille. But there was a teacher who could teach us maths but only the partially sighted learners could do maths up to matric and us blind learners were forced to take other subjects. I wanted to do maths because I wanted to become an engineer.”

Matshwane says that at Bartimea School they had recently acquired a new maths teacher who did not know Braille but would be expected to “hit the ground running”. It is mostly internal training of teachers that takes place, where other educators train their colleagues.

Fish-Hodgson says it’s essential to have assistants for partially sighted teachers. The report says that some totally blind teachers have to teach without an assistant, meaning that preparing for lessons as well as ensuring discipline, safety and concentration in class are incredibly difficult tasks.

Matshwane says that a teacher’s dignity can be compromised without an assistant and students can play around in class or try to take over the class if there is no assistant.

The employment of visually impaired teachers is also vital because they are often the ones who teach their colleagues Braille and are able to provide important role models to their students.

Access to learner-teacher support materials in Braille is also essential but this access has further decreased since the CAPS curriculum was introduced a few years ago. The report documents how there is a dearth of Braille textbooks, workbooks and teacher guides in schools in South Africa. Out of the 22 schools interviewed, 17 had never had access to any Braille textbook for the CAPS curriculum. The urgent provision of Braille and large print learning materials is another recommendation of the report.

“There [are] up to four learners sharing an outdated textbook which is a problem for learners in higher grades as they need enough time to study,” said an anonymous student at Khanyisa School for the Blind in the Eastern Cape in the report. The reason for this lack of textbooks is connected to a tender that had unrealistic timeframes meaning that no bidders applied. The report says that there has been no move to re-implement the tender.

Khumalo said that many teachers will write their own Braille notes for their students in lieu of textbooks and workbooks that should be provided. What adds to the difficulty of providing notes for the students is that brailing facilities break regularly and sometimes schools go months without getting these repaired as no one is skilled in their repair. The Perkins Machine is like a “pen and paper” to visually impaired individuals, with the report recommending that “immediate and urgent” steps are taken to ensure that all visually impaired learners have their Perkins Machine by the end of 2015.

Infrastructure at many schools for the visually impaired also does not cater to their needs. The report details how many schools were not initially built for the visually impaired and can pose dangers to students.

The cases of a student reportedly falling into an open pool and drowning, and three students dying in a fire because they were accidently locked in their rooms, are incidences that highlight the danger posed by inadequate infrastructure.

“According to me the quality of education at the school has deteriorated since the transition to democracy. Education does not accommodate special needs education,” said an anonymous educator in the report.

SECTION27 is set to present their report to the Parliamentary Portfolio Committee on Education early next year.

See also: Time to demand equal rights for blind people.

Support independent journalism

Donate using Payfast

Don't miss out on the latest news

We respect your privacy, and promise we won't spam you.

This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.