Diarrhoea cases in children surge in Cape Town

This spike comes after several years of improvement. A public health expert is worried that sewage spills might be the cause

Novangele Nyikana holds her baby daughter, who spent three weeks in hospital with diarrhoea. Her partner, Sicelo Kupe, holds their two-year-old daughter outside their home in Taiwan informal settlement, Cape Town. Photos: Steve Kretzmann

- Every year in summer diarrhoea cases – life-threatening to infants and children – spike in Cape Town.

- There was a massive increase in cases this year following several years of declining cases.

- The City’s tap water is unlikely to be the cause. The City blames the heat for causing food spoilage.

- A public health expert is worried that frequent sewage spills in the city mixed with the first rain showers of late summer/early autumn might be the main driver.

With her 18-month-old daughter suffering from acute diarrhoea in mid-February, Novangele Nyikana left the one-room shack she shares with her partner and children, and sought help at the Khayelitsha hospital in Cape Town. Thina, Nyikana’s 18-month-old daughter, was admitted and spent three weeks being treated for what is potentially a fatal condition for young children.

During this “surge season” (which starts in November and lasts until the end of May), 20 children have died from diarrhoea, according to City of Cape Town mayoral committee member for health, Patricia van der Ross, and provincial spokesperson Mark van der Heever.

On 6 April, less than a month after Thina was discharged, Nyikana’s two-year-old also came down with severe diarrhoea.

The family collects water from a communal standpipe about 30 metres from their home, and they share the area’s five toilets, only two of which were working, with about 50 other families. Sewage runs along the streets. There is hardly a street in the surrounding area that does not have broken and overflowing sewer covers.

On the walk Nyikana’s preschooler takes to kindergarten, people have no option but to step through or across puddles and potholes contaminated with sewage. Living in the close confinement of a one-room shack, it is almost impossible to stop contamination being traipsed into the home.

More than 4,533 children under five were treated for diarrhoea in City-run health clinics during February, two-and-a-half times as many cases as in 2021 (1,846 children), according to Van der Ross.

Since the beginning of surge season (November 2021) until the end of March, 14,150 children had been treated for diarrhoea at City-run clinics. An additional 4,024 children were treated at provincial hospitals in Cape Town, such as Khayelitsha hospital where Nyikana’s youngest child was admitted, bringing the total number of cases to 18,174. Cases for April and May still have to be accounted for.

Van der Ross said City-run clinics had recorded 14 deaths among children under five due to diarrhoea this season. Western Cape government deputy director of communications in the department of health and wellness, Mark van der Heever, said six deaths had been reported at provincial health facilities in Cape Town.

A spike after years of improvement

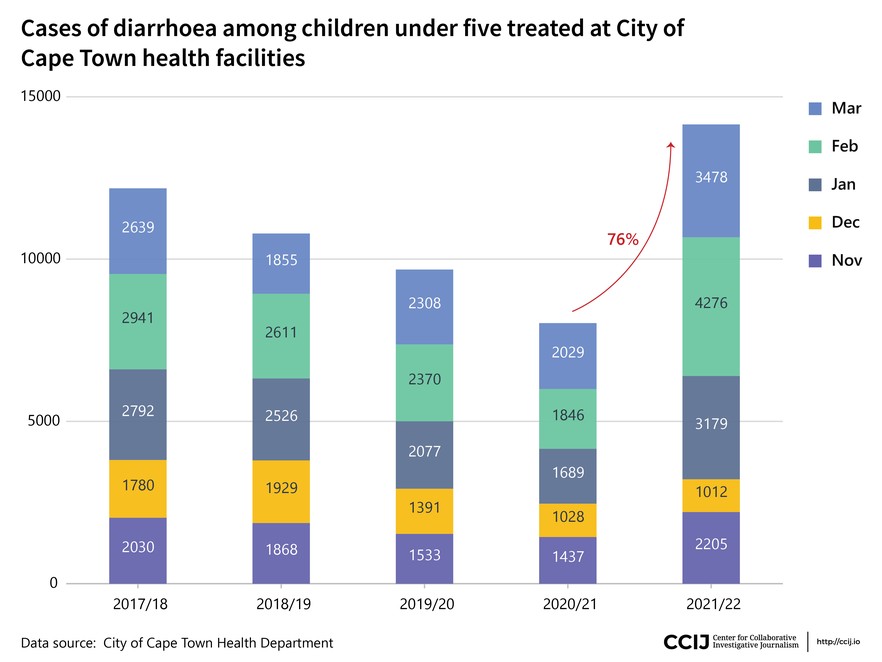

The graph below shows diarrhoea cases from 2017/18 until this year. There was a steady decline until last year, perhaps in part because of the Covid lockdowns when people’s movements were restricted to varying degrees. Then there is a massive spike in the 2021/22 summer.

But there is some good news: so far the number of diarrhoea deaths recorded by the City this season is lower than in the previous five.

Diarrhoea cases in children under five treated at City of Cape Town clinics dropped from 2017/18 to 2020/21 but then spiked in 2021/22. Graphic: Yuxi Wang

Possible sewage link

A rise in diarrhoea among young children in Cape Town is an annual occurrence. The City has stated, supported by the national Department of Water and Sanitation data portal, that the quality of municipal drinking water is not a cause.

The World Health Organisation lists diarrhoea as the second leading cause of child deaths, with poor sanitation facilities and exposure to sewage among the causes. Yet Van der Ross says the City health department is not investigating any links between sewage spills and cases of child diarrhoea.

In a media statement of 3 March, drawing attention to figures showing a 70% rise in cases for January 2022 compared to January 2021, the City attributes the spike to the summer heat causing food to spoil easily. It advises frequent hand washing.

A school child walks along a street polluted by sewage spilling from damaged and blocked sewers in Site C, Khayelitsha.

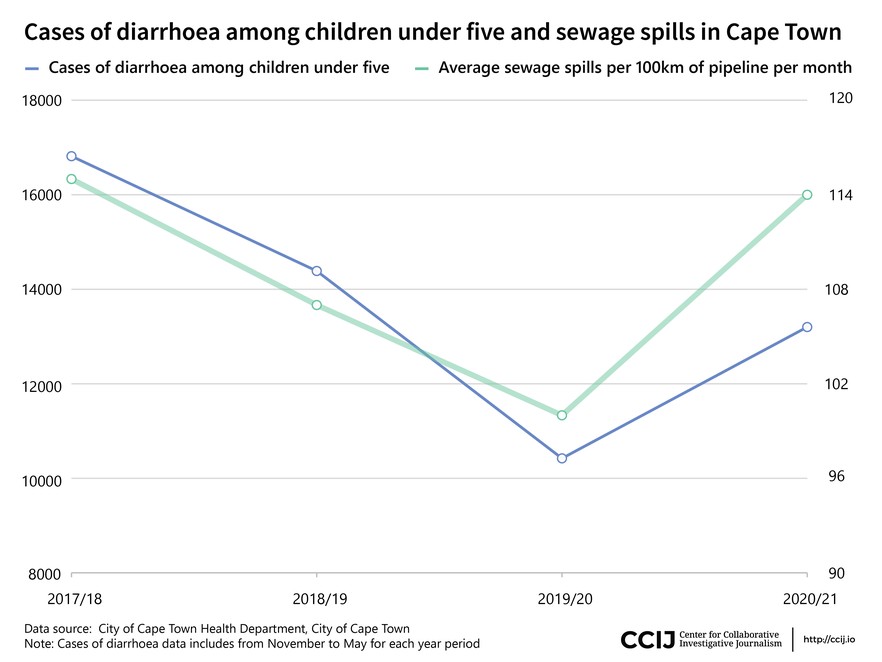

Senior lecturer emeritus at Stellenbosch University Department of Global Health Dr Jo Barnes says, “I’ve observed that a large number of people attribute the annual outbreak to the heat. However, by late November it is hot enough for food to spoil quickly, whereas the annual peak (in cases of child diarrhoea) is from mid-February to April, every year without fail.”

Barnes said years of research and consultation with paediatric specialists lead her to believe it is the first rain showers of late summer and early autumn, just ahead of the wet winter season, which are the main drivers of diarrhoea outbreaks.

She theorises that during the dry summer, faecal pollution from sewage overflows and open defecation where sanitation services are inadequate “piles up in the environment” but remains static as it dries from the heat. When the autumn showers arrive, this material then flows along streets and streams. Compromised sewerage infrastructure then also starts overflowing.

“It’s as regular as clockwork,” she said. “Within a week or two the number of diarrhoea cases picks up significantly. It only takes a few millimetres of rain to carry this mess back into circulation.”

It is children from poor families who are affected most, says Barnes.

Later, as the winter rains set in, the pollution is flushed from the streets and fields into the rivers and ocean, coinciding with a drop in reported diarrhoea cases.

This graph shows the correlation between child diarrhoea cases and sewage spills. It doesn’t include 2021/22. Graphic: Yuxi Wang

Sewage spills

On average, 323 sewage spills per day were reported across the City in January, according to Mayco Member for Water and Sanitation Zahid Badroodien.

And this figure probably excludes chronic sewage spills in areas such as Khayelitsha Site C, where residents have stopped bothering to report spills.

The City blames residents throwing objects, rubbish and building rubble into the sewer system for 75% of these spills. Informal or illegal building over sewer access points exacerbates the situation.

Asked about Site C, Badroodien said there were contractors on site but shacks had to be moved before repairs to sewer infrastructure could proceed.

Improvements planned

The City says it plans over the next three years “big investments” to upgrade sewers, pump stations, and wastewater treatment works. The big-ticket items include R755-million to increase sewer pipe replacement from 25km to 100km of piping per year, R529-million to upgrade and repair sewer pump stations, and R3.3-billion to upgrade wastewater treatment works. A further R860-million is to be spent on major sewer upgrades in certain parts of the city.

Badroodien said the City currently provides 57,000 toilets of various types along with cleaning services, and 7,640 taps to 257,000 households in informal settlements.

Over the next three years, R2.38-billion will be spent on water and sanitation services for informal settlements.

He said the goal was to halve the number of sewage spills by 2030.

Partnering with communities and responding to sewage spills was also “high on the agenda”.

Cape Town experiences over 300 raw sewage spills across the city per day, such as this one in Khayelitsha Site C.

Support independent journalism

Donate using Payfast

Don't miss out on the latest news

We respect your privacy, and promise we won't spam you.

Next: Young people have to choose between eating and looking for work, survey finds

Previous: Mom entitled to take ex-husband’s pension money for maintenance, says judge

© 2022 GroundUp. This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

You may republish this article, so long as you credit the authors and GroundUp, and do not change the text. Please include a link back to the original article.

We put an invisible pixel in the article so that we can count traffic to republishers. All analytics tools are solely on our servers. We do not give our logs to any third party. Logs are deleted after two weeks. We do not use any IP address identifying information except to count regional traffic. We are solely interested in counting hits, not tracking users. If you republish, please do not delete the invisible pixel.