SA researchers develop tool to detect HIV drug resistance

Paradoxically, it might be more useful in the United States than here

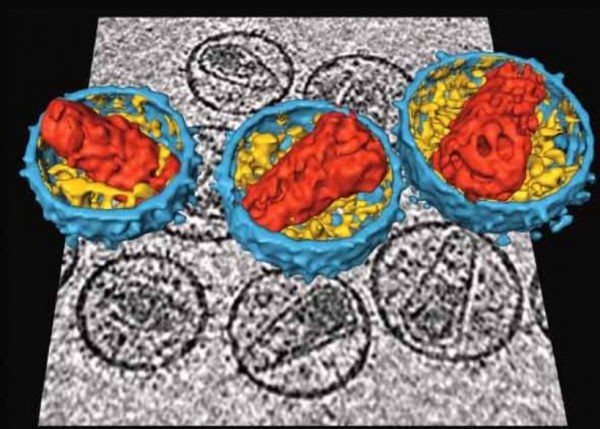

New tools developed by researchers at the University of the Western Cape (UWC) can pinpoint resistance to antiretroviral (ARV) therapies for HIV.

The HIV inside people taking ARVs changes all the time. Sometimes, especially if a person is not taking the right ARVs or isn’t adhering to their treatment, strains of HIV will develop against which the drug do not work. These strains reproduce and become the dominant HIV in the person’s body. The ARVs no longer work, and the person has drug-resistant HIV.

Experts in civil society, government and academia told GroundUp that ARV resistance was increasing in South Africa.

“I don’t think [ARV resistance] is an issue yet, but it will predictably become an issue,” says Dr Kevin Rebe, an infectious diseases specialist working with Health4men, a project of the Anova Health Institute. Health4men focuses on providing healthcare support for men who have sex with men.

“Like antibiotics, the more [ARVs] you use, the more resistance you will get.”

Prof Simon Travers, principal investigator of the HIV molecular evolution research group at UWC established Hyrax Biosciences, a company that developed out of UWC research that uses web-based DNA testing tools. Its flagship product, exatype, is an HIV drug resistance testing platform.

It is a web-service that analyses HIV DNA in patients to determine what strains of HIV they have and whether any of them are drug resistant. The company claims that this method is cheaper and more sensitive than conventional resistance testing.

Travers says that pathology labs – which have patients’ blood samples – can generate the data, and “then upload the data to our website. We analyse it and then the laboratories can send the report to the clinician. We’re a service that enables pathology labs to do sensitive, low-cost testing.”

The factor limiting the adoption of high-throughput sequencing – also known as next-generation sequencing techniques – for DNA is the data analysis, he says. Next-generation sequencing is a blanket term for genetic sequencing techniques that are faster and cheaper than previous methods.

“Because there is so much data, there’s no easy way to analyse that data and produce a clinical result that you’re confident of,” says Travers, who is also an associate professor in the South African National Bioinformatics Institute. “Next-generation sequencing can generate the data, but then they can’t analyse it.”

This phenomenon is being experienced globally – referred to as the “big data problem” – as people produce an unprecedented amount of data, whether through social media, Google maps or at the Large Hadron Collider, a particle accelerator in Europe. The difficulty is in making sense of the data and turning it into useful information that can be used to make decisions.

However, people in the field argue other countries, such as the United States, need HIV-resistance testing more than South Africa.

In the United States, it is estimated that one in 10 HIV-positive people is ARV-resistant.

Francois Venter, deputy director of the Wits Reproductive Health and HIV Institute, told The Times that only 350 of South Africa’s 3-million HIV-positive people were resistant to standard treatments. However, South Africa’s national department of health estimates that the number is much higher, at closer to 5% of infected people or one in 20.

Anova Health Institute’s Rebe says that South Africa’s advantage over countries like the United States is that “we had a robust triple therapy regime from the start”. “We will get resistance, but the robust triple therapy has shielded us…. We’re doing a lot of what can be done to reduce resistance.” Triple therapy is a single dose tablet containing three different drugs, which has been found to be very effective in suppressing HIV.

“In South Africa, the selection and use of the latest drugs, such as tenofovir as soon as that was available [has helped to reduce resistance]. A fixed dose to promote adherence [introduced] early on makes it easier for people to take their drugs, and this reduces resistance,” he says.

In the United States, people were put on clinical trials, and then there was “a sequential introduction of drugs as they were discovered and released. It has contributed to their level of resistance,” Rebe says. The major driver of resistance in South Africa is people not taking their drugs consistently.

The Department of Health’s Popo Maja says that if people fail their second ARV regimen, then they should be referred to a team of experts who will order HIV DNA tests. This only happens at the national department of health.

However, Rebe says that the sort of next-generation analysis offered by Hyrax Biosciences would be useful in a research setting. “Genotyping has a role, and scientists have had a look to see if a genotype assessment added anything to their patient assessment. In terms of patient level in Africa, it doesn’t add a lot,” he says.

It would be useful in research, though: “For the public good, it is good to know what kind of resistance is around, but I don’t think it will influence patient treatment.”

In the United States, on the other hand, resistance testing is recommended at diagnosis. Travers says that while the company is speaking to interested parties nationally, it’s also “engaging with impact investors from an international perspective”.

This technology, however, has other applications, such as tuberculosis drug resistance and detecting antibiotic resistance. “The way we’ve developed the platform, it is easy to branch out,” he says.

Support independent journalism

Donate using Payfast

Don't miss out on the latest news

We respect your privacy, and promise we won't spam you.

© 2016 GroundUp.

This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.