South Africa’s water wars

Ma Gladys Mphepho hovers over a pot on a two plate cooker in her shack in Papamani, an informal settlement outside of Grahamstown. “We do not have dignity,” she says, stirring the rice, flavoured with beef stock, that is her family’s Sunday lunch. “We do not know what it means to have dignity. Forget about any question of dignity,” says Mphepho.

It is a sweltering day in the heat of summer and Mphepho is talking about her daily struggle to live, which is exacerbated by the crisis that the people of Papamani, and greater Grahamstown, have with water. There are two taps in the whole of Papamani which serve close on 30 homes. Each home houses some five or six people. Do the maths, and that’s over 150 people who get water from two taps. That’s to drink, make food with, to wash with and to do anything else that requires water.

“When the tap runs dry or doesn’t work you have to take your bucket and go out and look for water. You can travel for the whole day and only come home in the evening,” says Mphepho. Grahamstown has experienced business and population growth that has put its arcane water system under pressure. Electrical failures in the city often bring with them a disruption in the water supply, and adding to the complexity is mismanagement and maladministration of the water system.

A local source, speaking anonymously, told of how a municipal water pump was retained by contractors for months because the repair bill for that pump had not been paid by the Makana Municipality. The lived reality of these service delivery problems is that taps can go dry for up to sixteen days at a time. The tragedy is that lives have already been lost because of this.

In March 2013, 34 year old David Makele left his home in Hlalani in the Makana Municipality to go and search for water. The taps had been dry for the whole weekend. He collected water from a municipal truck in a nearby district, but did not make it back. He collapsed and died on the way home.

Taps can go dry for up to sixteen days at a time.

The terrible irony is that Makele’s death came on the eve of SA’s National Water Week, which was promoted by the Department of Water Affairs from 18 to 24 March, 2013. Makele is one of many people across the country whose lives have been taken in the fight to the death for water – a battle that’s becoming known as South Africa’s water wars.

In January this year four people died after violent protests erupted in the Mothutlung township near Brits because of water shortages. Governed by the Madibeng Municipality, there’s been an ongoing history of corruption and maladministration in this ANC-led district. The service delivery has been wanting, and posts on the municipality’s Facebook page tell their own story of the area’s water problems. “Pathetic local municipality that does not care about the needs of its residents,” writes Lesley Mathe on Facebook. “Madibeng is the most corrupt of all the municipality in the North West,” vents Papi Nhlapo. “And now tanker truck owners are sabotaging the service delivery by destroying pipelines so as to continue receiving tenders from the municipality… shame on our government.”

“What I don’t understand is water is the number one basic right and we still have to fight for it,” writes John Seema, describing the agony of his family being forced to go without water, while (he claims) members of the local municipality drive new Audis. “My family is in great pain now because of your careless acts and selfishness. What kind of municipality are you mara? Your such a disgrace to the people of South Africa. Things like this make you think we should have stayed in the apartait [apartheid] regime service delivery was so much better. ANC MY SWAGGER. ANC MY SWAGGER SE GAT.”

Pampanani, Grahamstown. Photo by Jon Pienaar.

The anger evident in Makana Municipality’s Papamani and Hlalani, or Madibeng Municipality’s Mothutlung is a rage that’s seething across the country, and in some communities it’s spilling over into violence. Only this is a bloody battle that sees a government pitted against its own people as protests and police engage head on in what is often a fight to the death.

The rage is often long coming — as it was in the North West in February 2013, when residents from Hammanskraal and Steve Bikoville protested after going without a reliable, clean water source for as long as two months. “We get sick from the water. We develop stomach cramps and diarrhoea. Sometimes I even bleed when I have diarrhoea,” a protester told the Pretoria News at the time.

In its electioneering material the ANC claims that nine out of ten people now have access to water. “1994 – 10% of our communities had access to safe water,” a massive billboard over a main road in Pretoria reads. “2013 – more than 92% of our communities have access to safe water.”

A nationwide investigative journalism project undertaken by Eye Witness News (EWN) revealed a different picture from these figures, which are endorsed by the latest government census. “The last seven years have seen a dramatic drop in how communities perceive the quality of their water,” reports EWN. “Millions of people don’t have access at all while others report queuing for up to ten hours to get a single bucket of water.”

In June last year the DA’s provincial leader for the Free State, Patricia Kopane claimed that at least 26 towns in the province had “no water at all”, “water supply disruptions, or extremely unhygienic water coming from their taps”. In that same month, the South African Human Rights Commission (SAHRC) released a damning report on SA’s water crisis on the back of a deluge of continuous complaints about shortages, irregular supply and unsafe water for a couple of years.

The Human Rights Commission released a damning report on SA’s water crisis on the back of a deluge of continuous complaints.

The report showed that SA’s water and wastewater treatment plants are in a dire state of disrepair; that many households have access to infrastructure that was either never functional or was functional but has since broken or has not been maintained. The infrastructural problems, the SAHRC said, were due to poor original workmanship and a lack of maintenance.

The study showed that many households still used buckets and fields to meet their sanitation needs, and the SAHRC said this created health problems that spread through marginalised communities; and exposed women and young girls to sexual assault when they used fields for sanitation. Another equally damning report is expected from the SAHRC later this year.

SA’s constitution enjoins the state to realise people’s right to water, a right which the United Nations Human Rights Council notes is “inextricably related to the right to the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health, as well as the right to life and human dignity.”

On 13 April 2011 in Ficksburg in the Free State a man hailed by his community as a nation-builder and a civic-minded person died after facing off against police in an attempt to get them from aiming water cannons at elderly people who formed part of a service delivery protest. Andries Tatane became a lionized public casualty of South Africa’s ‘water wars’ – the battle by ordinary communities to assert their most fundamental right – the right to water security.

But Tatane’s tragedy reached the world only because his death was captured on television. For the most part those who die in SA’s water protests are ‘anonymous’ - the reports of their deaths are treated by the news as: “Another resident of Mothutlung, near Brits, has died after he allegedly tried to escape from a moving Nyala armoured vehicle”; or “On Monday, two people were killed allegedly by the police during the protest.”

Tatane’s tragedy reached the world only because his death was captured on television.

Tatane’s case was different. He had a face, a name and a narrative. In the month of his death protesters would gather outside the courts to try and secure justice for Tatane’s death (a justice that would never come). The placards these people held read, “We wanted water, but we got blood”.

Back in Grahamstown’s Papamani, Gladys Mphepho says that even when there is water, the quality is not good. “We fetch water with buckets, but the water tastes bad. You can see the sediment at the bottom, and it smells like ammonia sometimes.” (The ammonia smell is likely because Grahamstown’s water is being treated with chloramines - a combination of chlorine and ammonia that’s commonly used to disinfect water systems.)

In Pampamani, Mphepho says that complaints fall on deaf ears. “We complain. We meet with the mayor. We protest. But all we get are broken promises. I live with my three children and three grandchildren, and struggle for employment and to try and get money to survive. Our household tries to survive on the government grant we get of R750 a month, and the couple of hundred rand my son gets from public works projects,” says Mphepho.

The grandmother describes how the family uses a pit toilet, that must be relocated in a new section of the small yard when it gets full. “We dig a hole two metres deep and move the toilet,” she says. The word toilet in this sense is a euphemism. It is essentially a small lean-to that surrounds an old wooden box with a portal to a hole in the ground. Next to the box are a couple of pieces of newspaper.

Pit latrine. Photograph by Jon Pienaar.

The struggle for water continues across the country as communities try to survive failing water systems, municipal maladministration and corruption that robs people of their most fundamental rights. It is a struggle that sparks ongoing protests and violence, say the experts.

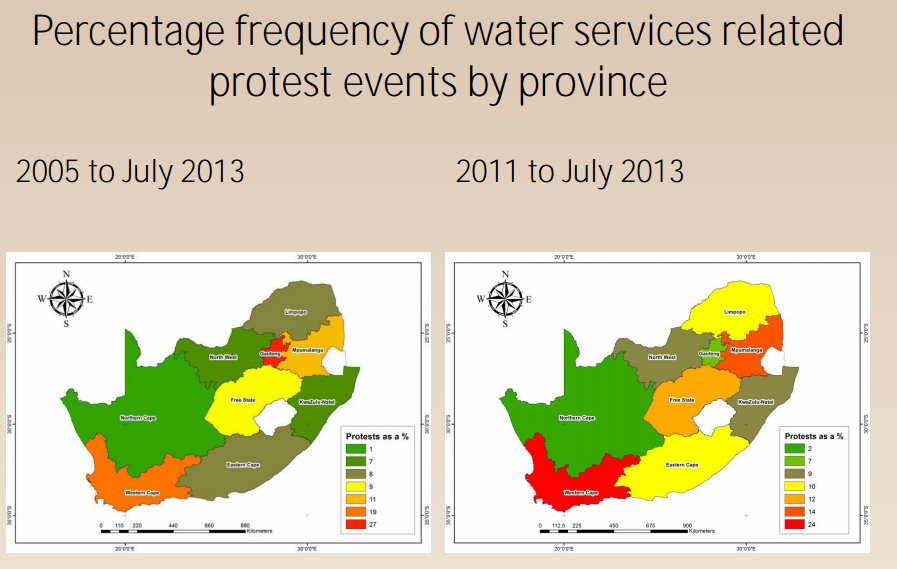

A study by Institute for Poverty, Land and Agrarian Studies (Plaas) shows protests related to water issues were becoming “more frequent and more violent”, and are increasing in geography. The report by Barbara Tapela shows that protest action was once an urban phenomenon, but that now “violent protests tend to occur in low to middle income residential areas.” And “recent evidence shows (an) increase in rural protests” too.

Infographic from Plaas survey – Social Protests and Water Service Delivery in South Africa.

The Service Delivery Protest Barometer set up by the Community Law Centre of the University of the Western Cape to gain understanding of the reasons behind these kinds of protests, shows violent protests have increased markedly since mid 2010.

Plaas’ Tapela says the causes for SA’s water protests are a lack of accountability, corruption, indifference and non-compliance on the part of water service officials. While triggers for the people who suffer from service delivery outages include mounting frustration and unmet expectations. As corruption, maladministration and system failures bite the anger is rising.

In short the simple story about water in South Africa is this:

Water is life.

No water. No dignity.

No water. No peace.

Read more

- Special Report: South Africa’s water crisis in Mail & Guardian.

- Water is life, but the struggle for it is deadly by Pierre de Vos at Daily Maverick.

- UWC’s Service Delivery Protest Barometer.

- Plaas’ survey: Social Protests and Water Service Delivery in South Africa.

- The Last Drop by Michael Specter in the New Yorker.

Support independent journalism

Donate using Payfast

Don't miss out on the latest news

We respect your privacy, and promise we won't spam you.

Previous: Police oversight bodies failing

This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.