Unions must take campaign for global minimum wage to BRICS

This is the first in a series of articles by Jack Lewis which puts forward ideas to start a discussion on the need for a programme which can unify the work which many great campaigning organisations are doing.

Forty years ago when I was a young activist I got out of bed because along with many others I believed in workers control and management of the state and society - old school socialism. It gave us a unifying vision. We urgently need something which in some ways unifies our struggles for better health, housing, education, safety and security and social justice, a vision which unifies society around a set of concrete achievable implementable goals which don’t require old school anti-market, nationalisation driven socialism, and which could provide a framework for thinking about the future. That said, the BRICS meetings seems a good starting point.

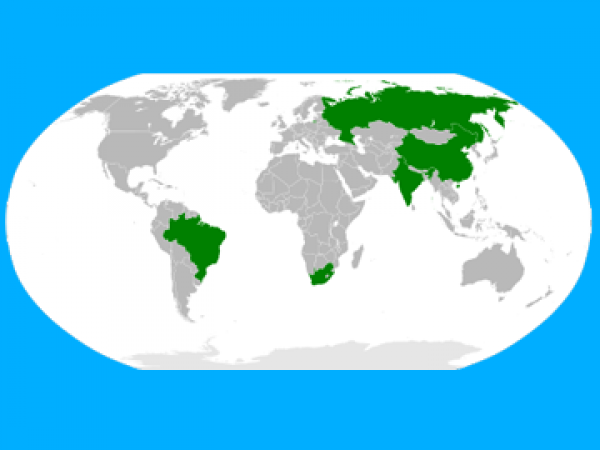

The BRICS group, Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa, brings together the leaders of the most important emerging economies in the world in Durban today.

What is the one most important thing South Africa should be advocating in the BRICS group?

The time is right for South Africa to lead the charge for the BRICS group to take on the World Trade Organisation and push for a global minimum wage based on purchasing power parity, a wage linked to the cost of purchasing a basket of basic necessities in local currency. This global minimum wage should be enforced by means of tariffs that would apply to exports from non-compliant countries.

Here’s why the time is right. Growth is slowing in all the BRICS countries. They all need to grow their domestic markets, none more so than South Africa. The depression of 2008 has caused growth based on exports to the so-called “developed” world to falter. The ongoing banking crisis, which started in Iceland, hit the US and EU and is now hitting Cyprus (whose economic success has been based on an easy rules for speculative and laundered money). As a result the US and Europe also face an unemployment and growth crisis. Redistributing income to the poorest in the economy is an effective way of creating demand for local goods and services which creates employment. This all requires a growth in domestic demand. Of course this should go hand in hand with infrastructure, education, housing and health spending.

We have heard a lot about wage flexibility. SACTWU does not like it and wants to enforce minimum wages reached through the bargaining councils. Some employers feel that would push their profit margins too much leading to further unemployment. The lowest bargaining council wage in rural towns like Newcastle in KZN is about $189 per month, R427 weekly or R1708 per month. Andre Kriel, General Secretary of SACTWU, is correct to point out that this is less than farm workers who now earn at least R525 per week according to the new minimum wages recently introduced after the Western Cape fruit and grape sector strikes. How does South Africa’s minimum wage in clothing and textile manufacture compare globally?

Bangladesh: The minimum monthly wage in Bangladesh stands at around $38.

Brazil: Brazil raised its minimum monthly wage to $326 in January 2013.

China: According to China’s Ministry of Human Resources, Shenzhen province will have the highest minimum wage, at $241 per month falling from there to as low $100 and less in Yunnan province. There is no national minimum in China.

India: Wages in places like Delhi are set at $130 for unskilled workers, $144 for semi-skilled and $158 for skilled labour. Many provinces are much lower. Enforcement is very weak.

Indonesia: A 44% minimum wage increase for workers in Jakarta, brought the minimum wage to $228 but it is not being implemented.

Malaysia: Malaysia pledged to bring in a minimum wage of $300 per month. Enforcement is weak,

Turkey: The minimum wage increased by 4.1% $441 in 2012.

Vietnam: The Vietnamese prime minister signed a decree on December 2012 raising the minimum wage for labourers by an average of 17% percent to between $79 and $113 per month.

As you can see SA is in about the middle of this list. Higher than Vietnam, Cambodia, Bangladesh and most importantly higher than India and most parts of China. While minimum wages are rising in China, there is a long way to go with many provinces with huge populations and very significantly lower wages than in South Africa to which manufacturing is migrating. Despite this, the trend is clear: wages are headed higher everywhere. And this is going to mean that the competitive advantage of lower wages is gradually being undermined. But this is a long and slow process. We can’t afford to wait while this happens.

When I look at this list, and I think of the incentives entrepreneurs receive in many of these countries, it is clear that the commonly held view that there is a “race to the bottom” is too simplistic. There is indeed downward pressure on wages in countries like South Africa (and developed economies) with relatively decent work conditions and wages from countries with poor work conditions and high productivity like China. When in countries like South Africa this downward pressure is resisted by pushing up wages, more unemployment is the consequence. Also, where there is pressure for lower wages, it is not so much between workers and factory owners, it is between countries. And it is collectively as countries that it has to be reversed. A global minimum wage is necessary to avert the downward pressure on wages that unions like SACTWU reasonably fear. Campaigning for minimum wages within countries only disadvantages countries with relatively higher wages and stronger labour laws. We also need to distinguish between high-tech production for export and low-tech production for local markets: the global minimum wage would apply to factories making goods for export.

For a greater share of the social product to go to the lowest paid there has to be an agreement between countries. When the output per hour per worker is brought into account, SA minimum wages are more seriously uncompetitive. In global competitiveness ratings SA rated 50th out of 59 countries beating Argentina at 55th place but weaker than all the other BRICS countries, with China ranked 23rd, India 35th and Brazil 46th.

Granted, this might be as much the fault of management and owners as workers, but no matter whose fault it is, it is true that productivity in SA is in general lower than our competitors. SA and many other countries need both a level playing field in wages paid in capital intensive export markets and wage flexibility in production for domestic markets. These two things are not opposed to each other; they complement each other. Bodies like BRICS and even the US and EU want to hear this; the era of arguing for each country’s right to drive down wages is over. Someone needs to take the lead, and who better than South Africa with our feet in both camps and our strong trade unions?

Best of all this struggle can be won. The ILO forced the questions of an international minimum wage onto the agenda of the WTO at its foundation in 1994. It remained on the agenda till 1996 when it was formally dropped. The WTO Ministerial declaration that emerged from a meeting in Singapore made it clear that labour rights are a question for the ILO, whose agreements are not legally binding, while scrapping tariffs that are legally enforceable is WTO business. Well, we need to get this question back on the agenda.

Its astounding that there is no campaign for this, no mass march around this at the BRICS summit led by COSATU’s comrades Zwelinzima Vavi and SACTWU’s Andre Kriel. Without global governmental regulations of minimum wages there will never be a solution to poverty wages (or high unemployment) in South Africa and many other places. And for those who believe it can’t be done, the same was said about the struggles to abolish slavery, an eight hour work-day, the abolition of child labour and many others. Of course it can be done. The new struggle is one that has to be fought internationally - not mainly against small manufacturers in Newcastle who are providing some measure of (underpaid) stability to the lives of low skilled and marginalised people there.

Lewis is a farmer, political economist and the former director of Community Media Trust.

Support independent journalism

Donate using Payfast

Don't miss out on the latest news

We respect your privacy, and promise we won't spam you.

This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.