Victory for women in polygamous marriages

Constitutional Court recognises their property rights

Women in polygamous customary marriages have won a major victory.

Thokozani Thembekile Maphumulo was the second wife in a polygamous customary marriage. She was never registered as a joint-owner of her home.

When her husband died, a will surfaced that stated, incorrectly, that her husband was unmarried. It left all his property to the eldest son of his first wife, Simiso Maphumulo. Since then, Simiso has been attempting to evict Thokozani from the home she has lived in for a number of years.

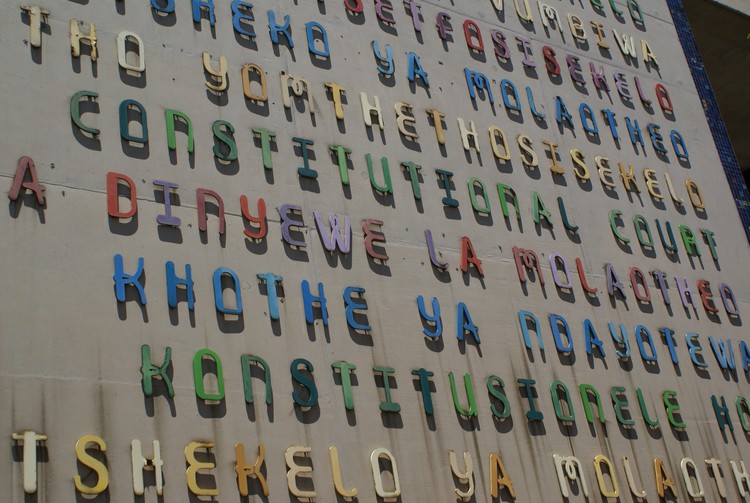

Thokozani’s is one of two stories that was at the centre of a case decided by the Constitutional Court on 30 November (the other story is very complicated so we have not told it). The court unanimously decided that section 7(1) of the Recognition of Customary Marriages Act, 1998 was invalid. This is because it unfairly discriminates against women by treating polygamous customary marriages before the Act came into force differently to monogamous marriages and polygamous marriages that took place after the Act was passed. For people in Thokozani’s situation this is very welcome news.

The Act was created to reform customary law, particularly where it discriminated against women.

An example is property: Under customary law, it used to be that a husband was given exclusive control and ownership of all matrimonial property, irrespective of whether the marriage was polygamous or monogamous. The Act changed this so that customary marriages were automatically “in community of property”. This means that each spouse owns an equal share of the property and has equal control of the matrimonial property. (This can be changed if both spouses agree and have a court-approved antenuptial contract.)

But section 7(1) of the Act meant that this reform would not apply to marriages that took place before the Act was passed. This meant that women who entered polygamous marriages after the Act was passed were given equal control of matrimonial property but women who got married before the Act was passed had no control unless their husbands and the other wives agreed to change the ownership scheme.

In 2008, the Constitutional Court declared the section invalid for pre-Act monogamous customary marriages but it still applied to polygamous marriages. The Court left the question on polygamous marriages open for Parliament to decide what should happen. But Parliament has taken no steps to clarify the position of women in polygamous marriages pre-1998. This has meant that, since 2008, monogamous marriages and polygamous ones that took place after the Act were automatically “in community of property”. But women who entered into polygamous marriages before the Act had no say in how the matrimonial property was used.

In this case, the High Court ruling found that section 7(1) discriminated on the basis of both gender as well as race and ethnic and social origin. Since no reason was provided to justify this discrimination, the High Court held that the section was inconsistent with the Constitution and invalidated it.

The High Court then made an order giving women in pre-Act polygamous customary marriages equal control and ownership over matrimonial property until Parliament passed legislation to govern these polygamous marriages. The High Court limited this invalidity so it would not affect customary marriages that had been terminated due to death or divorce. This meant that the applicants could not benefit from the High Court order.

The Constitutional Court had to confirm the declaration of invalidity by the High Court. Thokozani only became aware of the High Court judgement after it was made. Represented by the Legal Resources Centre, she successfully applied to join the case. The Women’s Legal Centre Trust also joined the case as a friend of the Court.

Justice Madlanga, who wrote the judgment, found that section 7(1) perpetuated “inequality between husbands and wives” who were in polygamous marriages before the Act.

Madlanga referred to the previous Constitutional Court decision, finding that the section discriminated on the basis of gender in a way that limited the dignity of wives in Pre-Act polygamous customary marriages. The judge also found that the section discriminated based on marital status. Section 9 of the Constitution forbids unfair discrimination on the basis of gender or marital status.

Madlanga noted that people in pre-Act polygamous customary marriages had the option to apply to court to have their matrimonial property situation changed if the spouses agreed. However, Madlanga found that where there was no agreement, women in these marriages were “at the mercy of their husbands”. This meant that the section infringed the right to dignity and the right to equality, and Madlanga found that the section was constitutionally invalid.

The Constitutional Court decision confirmed the High Court’s order to invalidate part of the Act but it changed the terms of the order, and went further by saying it could apply to to marriages that had already ended by death, such as the case of Thokozani. However, Thokozani will need to go back to the High Court to prove that her case falls under the court order. But the court also suspended the order of invalidity for 24 months to allow Parliament to rectify the unconstitutional section.

Until then, however, the Court felt that women urgently needed a way to redress the discrimination. So it gave them very comprehensive interim relief. Until Parliament passes the legislation, women who entered into polygamous customary marriages before 1998 will have joint ownership over matrimonial property, equal to their husbands. Also, each spouse will retain ownership over their personal property. This new regime will not apply to any estates that have already been wound up or to the transfer of matrimonial property that was finalised before the judgment, unless the people transferring the property knew about the judgment. If Parliament fails to fix the legislation within 24 months, the Court’s interim order will continue to operate.

The decision is an important step towards undoing historical discrimination against women.

Support independent journalism

Donate using Payfast

Don't miss out on the latest news

We respect your privacy, and promise we won't spam you.

Next: Cape Town’s sluggish judges

Previous: Durban activists defy bad weather to protest against council media ban

© 2017 GroundUp.

This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

You may republish this article, so long as you credit the authors and GroundUp, and do not change the text. Please include a link back to the original article.