Walking Joburg’s biggest baddest river: a very old church and a mermaid

Klip River Day 3: Eldorado Park to the Lido Hotel

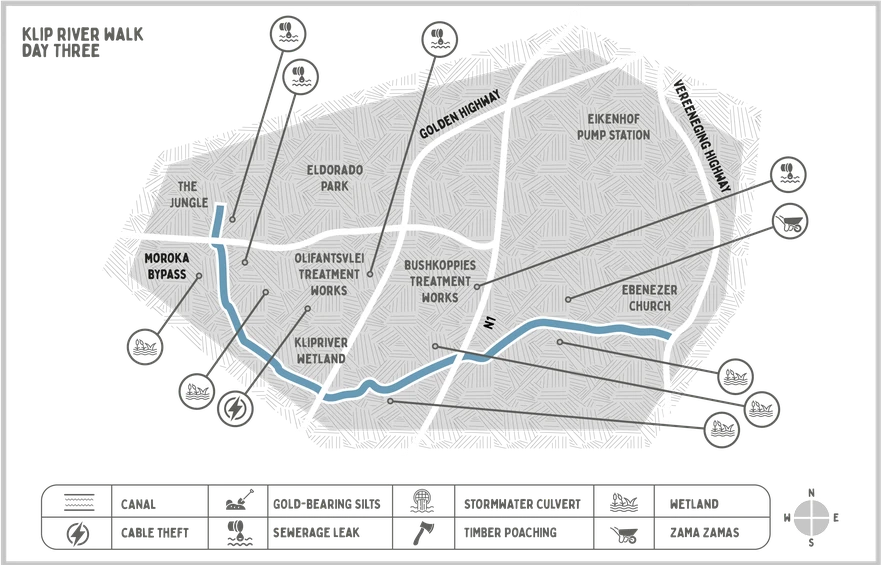

Map: Lotte Manicom/Surefire Communications

As the magnitude of Johannesburg’s water crisis becomes clear, water authorities are beginning to look at what it would take to use water from alternative sources, including Joburg’s rivers. To gauge the feasibility of this, GroundUp took a three day walk along Johannesburg’s Klip River. On the third day, our guides were: Julius Petersen, co-founder of Eldorado Park-based CBO Enviromentorz; Bobbos, a former soldier; Claude, an Eldorado resident; and Andrew Barker, a development consultant and the chairperson of KlipSA.

Walking Joburg’s biggest baddest river

This article is part of a three-part series.

Part one: Gold dust and gunk

Part two: Boerboels and cable thieves

Part three: A very old church and a mermaid

We started our third and final walk from the parking lot of the Aquatics Centre in Extension 9, Eldorado Park, which has not re-opened after being shut during the COVID pandemic. Beyond the lot’s low fence of whitewashed wooden poles lies the riverside park, known as The Jungle, once well-tended but now overgrown.

Once a popular recreation area, today The Jungle in Eldorado Park is overgrown with reeds and other plants.

“In the 1980s there were no reeds here. You could go right to the river’s edge, and there was an area for girls and an area for boys. If you wanted to meet girls, you came to The Jungle,” said Claude.

Claude had grown up closer to Thokoza, but in his youth would come across to “Eldoes” to party.

“There were so many clubs back then – Pink Cadillac, Out of Town; that’s how I came to know the place,” he said. “It was rough, but the gangsters fought each other, and they fought like men, with knives and pangas, whereas today I shoot you as I drive by. And there’s no end in sight, because people will say this one killed my brother, or my uncle, so I must settle it.”

Bobbos, nodding in agreement, recalled a time when the river was a territory fought over by rival gangs – the Dirty Boys and the Bristols.

“I don’t know if I’m younger than you guys or what,” Petersen broke in, “but I avoided this place. I was told there was a mermaid, in that pool over there, so I stayed back, and picked nectarines from the fruit trees that used to grow at the bottom of the river properties, until the owners cut the trees down.”

“Because you took the fruit,” said Bobbos, with a slight smile which Petersen ignored.

“At some point, I don’t know when, the river turned black. It never used to be black. Nobody comes here anymore,” said Petersen.

GroundUp had driven the area the day before with Andrew Barker, who shared Rand Water’s most recent Klip River water quality reports. These carry a colour-coded water quality index: blue means ideal, green acceptable, yellow is tolerable, and pink is unacceptable.

“The areas you will be walking through have produced a lot of pink readings recently,” he said.

“The unacceptable threshold for ammonia is four milligrams per litre. At the Nancefield industrial site, which we will be passing, Rand Water’s samples contained between 27 to 34 milligrams of ammonia, up to seven times what is considered dangerous to health. Nearby, at the Olifantsvlei testing station, e.coli levels ranged between 280,000 to 1.3-million counts per 100 milliletres. The threshold for unacceptable is 400.”

In the absence of people, birds had taken over The Jungle. Bobbos giggled at the sight of a guinea fowl cock running ahead of us at speeds that seemed impossible given the bird’s throw-cushion shape.

“You can’t eat those, there’s worms in the meat,” said Petersen.

“You can catch them, though, by soaking mielies in turps and scattering them. The guinea fowl eat the mielies, get drunk, and you just walk over and pick them up,” said Claude.

The Klip River Wetland (right of picture) functions like a gigantic, natural purification plant for the pollution Johannesburg puts into the Klip River.

We arrived at the edge of the Morokoa bypass and faced the vast green reed beds on the other side. This morass, officially the Klip River Wetland, was once an important water source for the city, but by 1910 authorities had built a very different sort of water operation on the edge of it – Olifantsvlei, the largest sewage disposal works in South Africa.

We traipsed the flooded road that separates the plant from the wetland, and all around us were the sounds of an invisible hydrology: the rushing, churning sewage in the mixing ponds on the left, and somewhere in the reeds of the wetland the belching of an outflow pipe.

According to one study, an estimated 253-million cubic metres of sewage and industrial water enters the Klip River every year, about five times the total storage capacity of the Vaal Barrage, into which the Klip River feeds. Once the city’s primary water source, the Vaal Barrage is today, in the words of water historian Johann Tempelhoff, “primarily a storage facility of sewage and industrial wastewater”.

The situation would be significantly worse, said Barker, if it wasn’t for Klipriver Wetland, “which has an extraordinary ability to deal with pollution”.

“In addition to all the sewage in the river there’s acid mine drainage from the West Witwatersrand, containing high sulphate and heavy metal concentrations. Researchers have shown that these pollutants get held up in the wetland, which transforms them into sulphides. Excess sulphide is then released as hydrogen sulphide gas. It [the wetland] even deals with uranium,” Barker said.

Olifantsvlei Treatment Works releases semi-treated effluent into the Klip River. Two other large treatment works in Johannesburg South - Bushkoppies and Goudkoppies - do the same thing.

A 2017 Water Research Commission report estimated the value of the wetland’s water purification service at up to R179-billion. Its ability to deal with the city’s poison is finite, however, and studies have shown that the wetland is collapsing.

“If it goes, it will be catastrophic for water users downstream,” Barker said.

Where the Golden Highway cuts through the wetland we found riverbanks covered in the paraphernalia of ritual: a matchbox and candle, a pile of ground clay, a yellow cap with snuff in it.

Above us on the bridge, a pedestrian shouted down, “People drowned here a few days ago, right where you are standing. Normally there would be inyangas there, doing rituals, but the authorities chased them away.”

A quick Google search confirmed that ten days before, two young adults had drowned during a cleansing ceremony in the Olifantsvlei area. A week before that, an 18-year-old male had slipped into the river in the Orlando area. In both cases, witnesses said the victims had simply vanished into the river. In both cases, it was days before the bodies were found.

The Orlando, Eldorado Park and Olifantsvlei sections of the Klip River are popular baptism and ritual cleansing sites, but a slew of drownings in 2023/24 has led to a crackdown on ritual uses of the river.

Sprawling reed beds kept us at some distance from the river, the course of which we now tracked on phones. We came to the gates of the SAFA technical development centre, which Google Maps still lists as “Fun Valley Leisure Resort”, and traced the wall of Olifantsvlei cemetery all the way to the N1 highway. Large birds went by overhead, including a heron with white ventral feathers and a drooping neck. In the reed beds on our right were red bishops, paradise fly catchers, and squabbling cattle egrets.

Dumping in the river reserves and other open areas is a major problem in communities south of Johannesburg.

We walked northwards up the highway until we reached a stony ridge line running parallel with the river. A scree of tailings next to a small settlement indicated there had been informal mining activity. There was a kraal to one side of the shacks, and out of this a large herd of cattle ran downslope into the verdure between the ridge and the river. In among the cattle were several dogs and three men. “Basothos,” said Petersen.

There were willow trees growing all along the riverbanks, and under one had been left several pieces of coloured lace – turquoise, pink and grey. Petersen grabbed a bunch of green branches and swung out in the direction of the river. The branches snapped, sending him crashing to the ground. This amused Bobbos deeply.

The ridgeline and the river converged, forcing us up into terrain so jumbled we needed to watch our feet and failed to notice a church until its corrugated walls were right in front of us. Made entirely of zinc, the church was the largest structure in a compound of buildings. Animals cast from concrete – a flamingo and a springbok – had been placed at various points of a well-watered lawn, running out to a two-strand perimeter fence. A marshland ebbed as the property’s eastern border, ending at nearby Vereeniging Road. Undeveloped land swept upslope for several kilometres to the concrete structures of Rand Water’s Eikenhof pump station, nestled at the foot of the Klipriviersberge.

The Ebenezer Congregational Church on the banks of the Klip River is a 120 years old, and families of Griqua/Khoisan descent have been living continuously here for just as long

“What is this place?” wondered Petersen.

Barker had explained that the church had been built by the London Missionary Society in the first decade of the 20th century, to minister to farmworkers and their families, mainly of Griqua/Khoisan heritage/ Some of their descendants, he said, still live at the site.

A young woman winched water from an old bucket well. A child streaked naked out of one of the church buildings, a woman shouting, “Kayden, ek gaan jou klits!”.

The gate was kept open by grass growing up its frame. A man with a buckskin band around his forehead came out to greet us. He introduced himself as Izak Matthys, one of several Matthyses who grew up in the area and attended the church school. Plastic chairs were arranged for us on the lawn under a large syringa tree.

“Here we sit in the shadow of oppression,” said Izak, fixing us with a challenging stare, before cracking up. “You should see your faces – so serious!”

“The missionaries who built this place found us living here on the farms and in the spaces between the farms. They came to save the brown people from their ‘satanic ways’,” he said.

Izak Matthys grew up on Eikenhof Farm.

In the 1960s, most of the families living on the area’s farms had been relocated to newly created “Coloured areas” like Eldorado Park, but some, like Izak’s late cousin Chief Adam Mathyssen, had returned.

“It was Adam’s vision that the church would become a place where people could reconnect with their roots. He died in 2017, and we got permission to bury his body in the old community cemetery nearby. This place was subsequently renamed Adamslof,” Izak said.

The river had been a big part of their childhoods.

“Our elders called this place /huni /Gaeb, which means an elbow in the river, but in fact they didn’t want us going near the water. They used to warn of this big snake that would appear from time to time, but I think the thing that worried them was the fact that Hindus scattered the ashes of their dead in the river, upriver at a place called Kliprandjie,” said Izak.

He would sneak away to watch these ceremonies, “because they would also throw money and coconuts into the river, and we would fish the coconuts out around the next bend and enjoy them.”

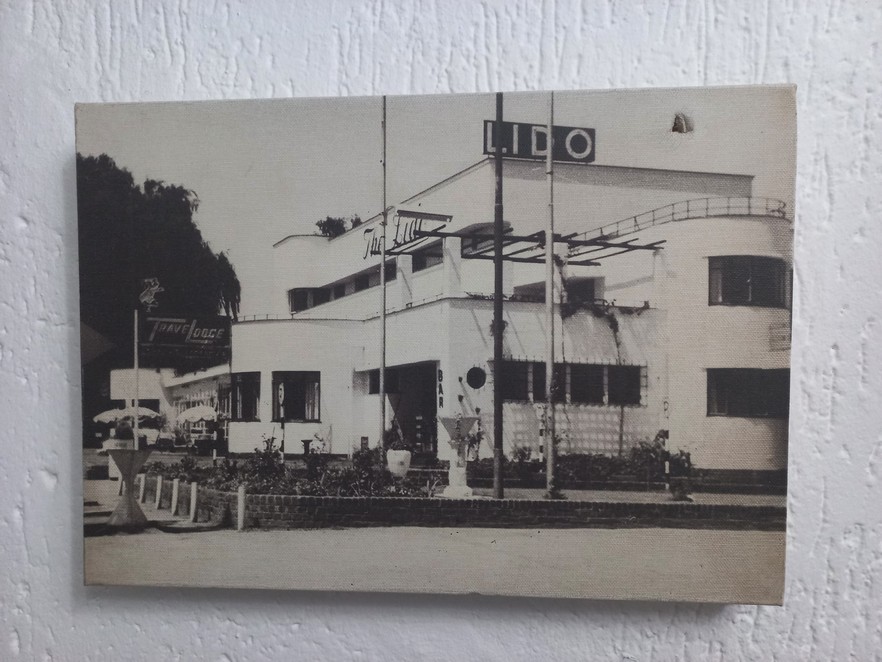

GroundUp’s Klip River walk ended at the Lido, an art deco hotel off Vereeniging road that was famous for its dance floor.

Izak gazed off at the headlights of the cars passing on Vereeniging road, lighting up the ship-themed façade of The Lido Hotel.

“When I was growing up, if lights appeared at night, our elders used to say it was grond dwergies that live in holes next to the river, and we believed them because there are big holes around here. They are some of the oldest mine shafts in the Johannesburg area. I think the story about grond dwergies started because they used to see miners coming and going with headlamps. To this day, I will not go anywhere near those pits,” said Izak.

Our circle broke up when Bobbos stood to stretch his legs. Izak walked us the final half kilometre to the road, pointing out where the ground was boggy.

“You don’t want to get your shoes wet, not at this time,” he said, and perhaps triggered by some old memory, he burst out laughing, and the rich sound went out over the empty veld.

Support independent journalism

Donate using Payfast

Don't miss out on the latest news

We respect your privacy, and promise we won't spam you.

Next: Eastern Cape villagers fund their own water supply

Previous: Injured Mister Sweet workers yet to be compensated

© 2024 GroundUp. This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

You may republish this article, so long as you credit the authors and GroundUp, and do not change the text. Please include a link back to the original article.

We put an invisible pixel in the article so that we can count traffic to republishers. All analytics tools are solely on our servers. We do not give our logs to any third party. Logs are deleted after two weeks. We do not use any IP address identifying information except to count regional traffic. We are solely interested in counting hits, not tracking users. If you republish, please do not delete the invisible pixel.